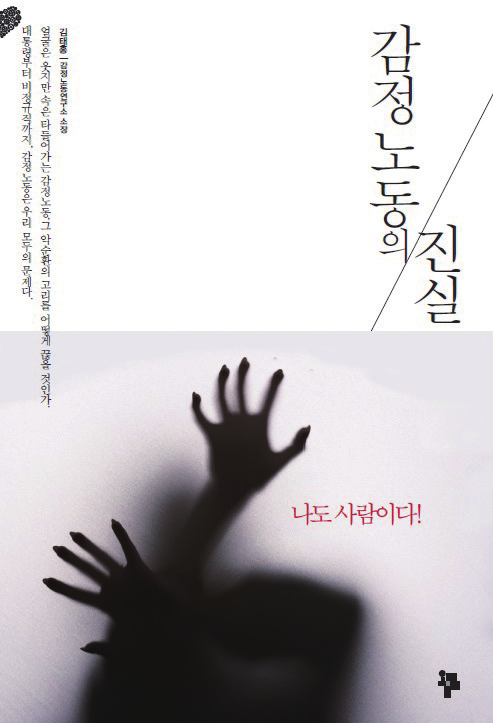

Emotional laborers of the Korean society

“THE CUSTOMER is the audience, the employee is the actor, and the work setting is the stage.” Just as the phrase by marketing scholars Grove & Fisk indicates, many of today's employees have become actors forced to suppress their emotions to please their audiences. Of course, an act of kindness can always be a positive energy boost, but should the ‘actors’ bow down and kneel down on their knees even when their audiences blurt out abusive language, sexually harass or physically assault them? This unthinkable humiliation is, in fact what a category of workers now classified as ‘emotional laborers’ are forced into in their everyday routines. We can no longer avoid this issue, because all of us including our family, friends and lovers, already are, or might soon become, victims of intense emotional labor.

Understanding the term 'emotional labor'

The term 'emotional labor' was first coined in 1983 by a sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild in her book The Managed Heart. Hochschild defined the term as follows: "the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display." If this kind of academic definition isn’t clear, here is an example provided by Hochschild: when a flight attendant pushes a food cart along the passageway, this is "physical labor." When a flight attendant has to prepare for a crash landing, this is "mental labor." When a flight attendant has to deal with an offensive passenger with a smile on her face by suppressing her feelings of anger and sadness, this is what you may call "emotional labor." According to Kim Tae-heung (Head, Emotional Labor Institute), the relatively new idea of “emotional capitalism” provided by sociologist Eva Illouz, based at Hebrew University in Jerusalem better explains the emotional labor common in today's society. She said the society now is in the state of emotional capitalism in which genuine, sincere relationships and love have been replaced by economic behaviors such as calculation and self-interest. In other words, emotional labor is now everywhere to be found, even outside workplaces. According to the Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education & Training (KRIVET), the jobs that demand high level of emotional labor include flight attendants, salespersons, telemarketers, nurses, and social workers, but emotional labor now also includes white-collar workers dealing with their superiors, customers, and cooperative firms. College students are also a group prone emotional labor, said Kim. "Since college students mostly have a contingent job, which in lots of cases require the employees to directly deal with customers, they are more exposed to meeting rude customers without any knowledge of what the society is actually like."

Emotional labor poses serious psychological effects that exceed the respective tolls taken by physical, cognitive and mental labor. The recently accumulating statistics on emotional labor all indicate that emotional laborers are afflicted with serious depression, anxiety, and burnout. According to research conducted by Kim In-a, a professor at Yonsei University’s graduate school of public health, laborers in South Korea who answered "very much" to the question "do you hide your emotions during work?" are about three times more likely to have considered suicide within the past year than those who answered "no" to the same question. No country in the entire world has documented such a high rate of depression among emotional laborers.

What’s more, some employers are now adding even heavier loads on the shoulders of emotional laborers. Though it might sound extremely odd, some employers have begun employing not only their laborers but also their customers. These customers are named "mystery shoppers" or "interior monitoring agents," and they are hired to function as a human surveillance camera by acting like a sensitive, rude and absurd consumer; by intentionally acting rude, they can easily test, evaluate and often downgrade the emotional laborer's kindness, appearance, and sales technique. “Mystery shopper” even has been established as a career, and now you can easily find an education center that trains professional “mystery shoppers” on the Internet. Of course, this might be an effective measure to improve the quality customer service, but such a seemingly absurd occupation being widely recognized as a job is a clear indication that the society is instigating more emotional labor. Employers are not the sole responsible subjects; the society itself has fostered an atmosphere in which emotional laborer and their efforts are neither respected nor protected.

What makes life even more difficult for emotional laborers is the very low exchange value between labor and wage. Among all types of labor, emotional labor is the most undervalued. Whether one has a high-paid or low-paid job, the emotional labor itself is never appropriately compensated. Most of the high payments that lawyers and doctors receive, for example, is for cognitive labor, whereas their emotional labor is uncompensated. Often times, lawyers act like psychology advisors listening to their clients' life difficulties with forced smiles on their face, but this dimension of their work is hardly noticed. As seen in current circumstances, the burden that employers load on their employees is not about direct and illegal harassment – instead, it is far more subtle and insidious. Elevating stress with “mystery shoppers” and not providing enough compensation for mental fatigue nevertheless amount to violence that intensifies the sufferings of emotional laborers.

What is going on in Korea?

After about 30 years since the term ”emotional labor” made its first appearance to the world, it began gaining attention in Korean society, as well. A series of events relevant to “emotional labor” received extensive news coverage and revealed the severe humiliation faced by in Korean society. Fortunately, this attention served to raise consciousness towards the issue. One notorious incident came when an POSCO Energy executive allegedly harassed a PLEASE ADD AIRLINE flight attendant on a 12-hour-flight. Another shocking event followed, when the chairman of Prime Bakery allegedly assaulted a hotel worker, and this issue also sparked public controversy.

With this series of events, the rights of emotional laborers came into the limelight and Han Myong-sook, a member of the House Democrats in 2013 even proposed a bill aimed at protecting emotional laborers. Evidence of increased public concern in Korea on the issue can be seen in the library database in Yonsei University. Only 7 academic dissertations with the keyword “emotional labor” can be found in the Yonsei University library database in the years before 2002, then 12 from 2002 to 2004, then 21 from 2005 to 2007. And then, the numbers rise dramatically to 155 from 2008 to 2011, and from 2012 to the present, the numbers of dissertations on the subject has surged to 219, which shows Korean society's rising awareness toward emotional labor. Sadly, even with the growth of society's rising interest, no specific improvement has emerged. Unlike in Europe, where job stress from emotional labor is treated as a violation of the employee's basic rights, South Korea's current laws do not regard the side effects of emotional labor as akin to an accident on the job, and no strict criteria specify who can come under the category of emotional laborer and be protected. Han Myong-sook's bill also failed to develop to carry a legal binding force. Then, for what reason did Korean society overlook the pains of emotional laborers, leaving them neglected, at least for the time being, as victims of emotional capitalism?

A major reason can be found in the attitude of Koreans toward their jobs and workplaces. Most East Asian countries tend to have a strong attachment to groups that they belong to, and one's occupation is a typical example. In such a society, an occupation is not simply a job, but a vocation. Workers create almost a kinship-like bond with the company and take huge responsibilities as employees. Therefore, employees usually have a hard time recognizing that emotional labor is something they can resist. Being unable or unwilling to take a critical or controversial position in the workplace, employees make it all the more difficult to reach a fundamental solution that would save them from further damages.

The strong hierarchical order deeply ingrained in the minds of Korean people further exacerbates the situation. The so-called gab-eul relationship in South Korea which is equivalent to a master-servant relationship, is often applied between workers and their employers. An anonymous college student who has held several part-time jobs said in an interview: "When I go out in the society, I feel like I am always the "eul". My employer would always forget to pay me at the promised time, and when I asked him for my payment, I had to be treated as an impudent young worker. Even though I am treated this way, I have no other choice but to suppress my anger because this is my only chance to earn money." Another gab-eul relationship example is between customers and workers: it is created with the ingrained Korean thought that "customers are king." The word for customer in Korean is son-nim, and nim is an honorific title which indicates much respect. These little details that we can easily miss are in fact telling us about the hidden violent relationships in Korean society.

Another twisted perception exists in Korean society about "customer satisfaction” and "customer impression." According to Kim, the sinking of the Sewol ferry can also be blamed partially on this misled idea of "customer satisfaction" and "customer impression.": "The Cheong-hae-jin Shipping Company that owned the of Sewol ferry won first place four times in a row in a customer approval rating proceeded by the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries. However, none of the items on the rating included safety related issues, while most of the items were about the quality of emotional labor. The priorities are clearly messed up." Prioritizing only the quality of emotional labor is an inappropriate evaluation method that only worsens the problems caused by emotional labor; the fact that “customer satisfaction” takes priority over factors such as safe passage show how much excessive weight South Korean society places on on bowing down to customers.

How can we protect emotional laborers?

It is time we think of a meticulously planned healing process for emotional laborers. All the psychological issues facing emotional laborers including depression, anxiety, and burnout are in need of immediate attention and resolution. Fortunately, institutional changes are being made in some companies to protect their employees by providing extra pay and vacations for emotional labor. E-mart, the large-scale discount store, has taken a positive step with its newly arranged program aiming to help employees recharge their energy consumed by mental stress. Homeplus, another large discount store, also announced a collective agreement in January to acknowledge the workers' emotional labor and has developed a manual to help workers cope more effectively with customers who confront them with hostility or violence. Despite the progress, companies that lack institutionalized measures for emotional laborers greatly outnumber the companies that taken steps forward, and it is time to note that the countermeasures that come after a scratch can never get to the root cause of this issue.

Before more sweeping changes can be implemented across the spectrum of everyday life, greater public awareness is needed.. The entrenched gab-eul relationship needs to change, and a better consumer culture needs to be created. In the case of the United States, the society has a stronger public bond of sympathy towards emotional laborers and understands that even white collar workers are bound to emotional labor. Therefore, many American employers have created a "smart work" environment that allows workers to work in any place at any time. The numbers of employees that work in such an environment reached 13 million people whereas Korean society is still less generous towards such a flexible work-setting. However, some positive changes are being made in Korea. In Jongno-gu, the head in August implemented a two month "Campaign to create a business and consumer culture in partner with emotional laborers". The goal of this campaign has been enhance working conditions and improve human rights for female and emotional laborers. Active social movements by the Emotional Labor Institute (ELI) and labor unions also provide a big helping hand for emotional laborers. ELI provides education for emotional laborers to control their stress, thus can help emotional laborers to escape from psychological issues and survive in the workplace. It is also time for labor unions to realize that emotional labor is being forced upon workers and that it should be compensated and also reduced. Korea should also follow the lead of European countries that have classified some forms of job discrimination that violates human rights.

* * *

Psychologist Barbel Wardetzki once wrote that when a mental bruise is headed inward, it hurts the soul, and when it is headed outward, one will explode in anger. If emotional laborers are left unprotected, many will end up either suffering from serious mental illness or venting their anger on other innocent victims, often other emotional laborers. South Korean society runs the risk of falling into a vicious cycle in which many people become both victims and perpetrators of emotional labor. It is urgent for us all to acknowledge, respect, and protect our emotional laborers.