Analyzing socio-political problems of drug trafficking in Latin America

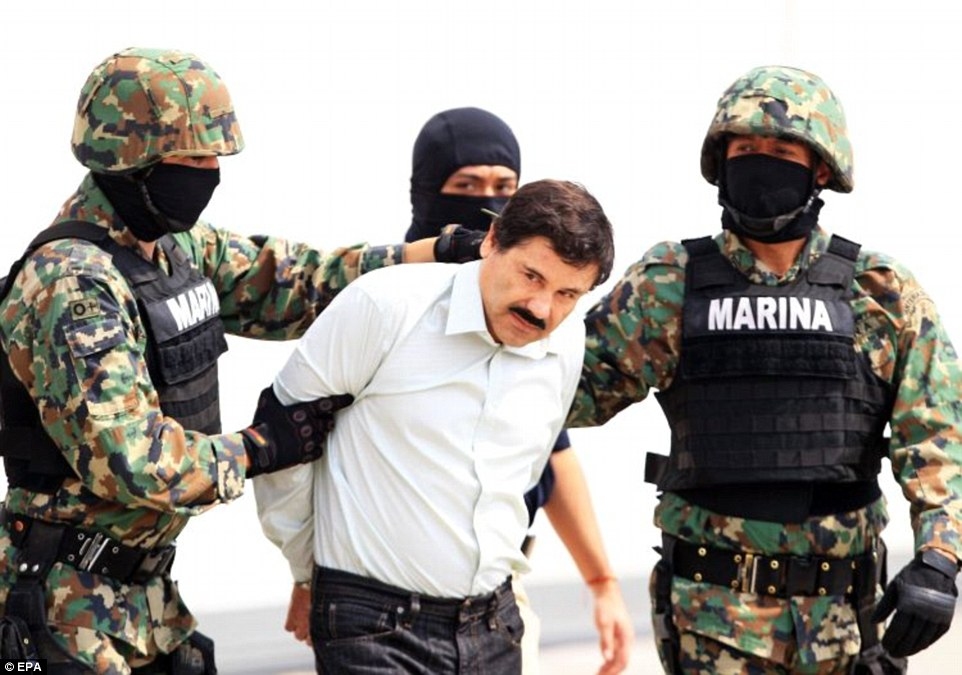

THE MILITARY confrontation with the notorious Mexican drug lord Joaquín “Chapo” Guzmán-Loera began when a citizen complained about a group of armed forces in the Mexican city of Los Mochis. Mexican marines were quickly able to capture El Chapo and his crew with their pile of rifles and ammunitions. “Today our institutions have demonstrated one more time that our citizens can trust them,” announced President Enrique Peña Nieto of Mexico after this incidence. However, his announcement did not relieve Mexican civilians as they knew that drug crime has been ongoing for years. In fact, with drug smuggling deeply permeated in Latin American society, its prevention is not easy. But why so?

Drug trafficking: crime or business?

Drug trafficking in Latin America gained momentum during the 1980s with the mass production of coca-leaf in Peru, Bolivia, and Colombia. It began modestly, with drug traffickers secretly exporting cocaine and marijuana to the United States through suitcases. As these narcotics crossed each country, their monetary value increased, and by the end of the route, their price was five times higher than the original price. The tremendous profit gained through drug trafficking lured poverty-stricken people into this narco-business called drug cartel.

Drug cartels in Latin America are not only drug smuggling businesses, but also profit-making criminal organizations. What began as a small drug trade became an empire of criminal activities involving human and arms trafficking, assassinations, kidnapping, money laundering, and bribery. Ironically, many drug lords are successful in accumulating massive wealth through these illegal activities. Pablo Escobar, an infamous drug lord in Colombia who led the Medellín Cartel, was listed by Forbes as the seventh wealthiest man in the world in the 1980s, which was mostly due to the great profits earned from his cartel’s selling of cocaine to the United States. This came at a cost of sacrificing thousands of innocent lives for his drug smuggling business. The rising Mexican drug kingpin El Chapo is exporting even more narcotics abroad. The New York Times states that his estimated annual revenues exceed $3 billion, which is comparable to that of Netflix or Facebook. What these two drug lords have in common is that they both come from an impoverished background. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 25% of the Latin American and Caribbean population live under poverty as they earn less than $4 a day. The profitable drug business appears attractive enough for these poor people who are looking for an easy way to earn money while dreaming of becoming the second El Chapo.

Drug cartels against the corrupted government

Curbing drug trafficking in Latin America is hard because drug trafficking is perceived as part of the culture. Most people who have joined drug cartels are usually poor and uneducated. “A friend of mine told me about this business," said Rafael, a teenage hit-man from Sinaloa Cartel during an interview conducted by BBC. “He was part of this team. So I joined too. I was 14 years old. I was not good at school. I like this.” Like Rafael, it is normal for many uneducated teenagers to follow their peers and join drug cartels. They search for their new social identity from drug cartels which heighten their sense of belonging outside their vulnerable home.

Furthermore, the government faces limitations in deterring drug crime because the government itself is being challenged by drug cartels. Drug cartels have their own system which highly resembles that of the federal government. They have their own central leader, supervisors, hitmen, and operators who all coordinate and work under a set of rules. Consequently, they pursue independence from government control to protect their lucrative business, and they are dauntless to face any danger against the government. For instance, on Jan. 2th of 2014, Gisela Mota, the newly elected mayor of Temixco, was murdered in her house. The murder was carried out by drug gang members, and the reason is presumed to be her political campaign to fight against drug trafficking by imposing restrictions on drug routes to Mexico City. Such murders of political authorities are common in Mexico; the National Federation of Municipalities states that for the past eight years, most of the mayors in Mexico have been killed by drug traffickers. The cost of eradicating drug cartels is increasing as narco-traffickers increasingly become vicious to the authorities.

As drug traffickers challenge the government each time, problems arise regarding weak surveillance system and government corruption. Members of drug cartels easily bribe and work in concert with the corrupted local police. While the members carry out their criminal activities, the police defend their smuggling business and turn a blind eye on their crime. Moreover, according to the UN, only 1-2% of the 102,696 homicides that took place in Mexico between 2006 and 2012 were investigated for conviction. This means that the majority of murders were not thoroughly investigated or even prosecuted, verifying the weak role of civic institutions.

In fact, the federal government’s credibility itself is often put under question. On September 2014, there was a massacre of activist students from Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers' College in Mexico. They were on their way to commemorate the 1968 Tlatelolco Massacre where many student activists were killed by the federal police for their political opposition. The students were stopped during their trip and were confronted by some unknown forces until they were kidnapped. Mexico’s attorney general, Jesus Murillo Karam announced that the corrupted local police had handed them over to an infamous drug cartel, Guerreros Unidos. However, after a year, the Inter-American Commission reported that the federal police and the Mexican Army were present at the scene, and raised doubts on whether the central government had announced the truth. Citizens have no-one to trust as both central and state governments distort the truth about drug cartels. As a result, more and more people distrust the government as they believe that the government has been bribed by drug cartels.

Kicking the start of U.S.-Mexican collaboration

Most of the infamous drug cartels are located in Mexico, the closest route to the United States. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) reports that major Mexican cartels are operating in the United States, where they earn most of their profit. Therefore, U.S. involvement is crucial to solving drug trafficking problems. One of the reasons why drugs flow from Mexico to the United States is that the U.S. demand for narcotics is high. This indicates that a huge, yet surreptitious drug market exists between Mexican drug cartels and U.S. drug dealers. Drug cartels develop their own agents to assist drug distribution in the United States. Furthermore, according to a report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the route to smuggle drugs to the United States is also used to transport weapons to Mexico. Members of drug cartels legally buy weapons from the United States and illegally send them back to Mexico. The process is discreet and hard to detect because of the great amount of goods that are smuggled between the two countries.

Despite the heightened importance of U.S.-Mexican collaboration, current Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto has been limiting the U.S. military presence in Mexico. Although he approves of the U.S. assistance through technology such as surveillance drones, he emphasizes that the operation to fight drug cartels should be handled by the Mexican authorities. When El Chapo escaped last year, President Peña was criticized for holding back extradition of captured drug lords to the United States, demonstrating that Mexico alone can handle these kingpins. Furthermore, he strayed away from the kingpin strategy which targets the capture of drug lords and shifted his focus to prevention strategies by increasing funds on social programs to deter people from joining drug cartels. Nevertheless, government corruption cases, such as the September 2014 massacre of activist students, raise doubts on the effectiveness of the president’s security policies.

In order to gain back citizens’ trust, President Peña must show that his administration can cooperate with the United States in combating the drug war. El Chapo’s recapture by Mexican authorities with the U.S. assistance points out the importance of stronger cooperation between the two countries. Continual assistance by the United States will aid Mexico to eradicate corruption in police and military forces. Mexico will have to open up for more U.S. military back-up while the United States will have to realize its inevitable responsibility to stop the flow of drugs and weapons across the borders. With ever-stronger influence of drug cartels on both nations, Mexico and the United States need to negotiate possible ways to deter drug cartel activities.

* * *

President Peña’s tweet, “Mission accomplished” after the capture of El Chapo, must actually mean “Mission begins.” The roots of the problems of drug cartels are embedded in Latin America’s political system and its socio-economic condition. It is not an easy task to terminate drug-related crimes. However, efforts to restrict such activities should be made, and mutual cooperation will open up the path towards a crime-free society. Drug trafficking is not a matter of looking for whom to blame. El Chapo’s recapture must be the relevant start to lighten up U.S.-Mexican relations, which is crucial in saving thousands of innocent lives in both countries.

Yeo Ye-rim

yryeo94@yonsei.ac.kr