Controversies regarding Seoul’s Youth Allowance Project

SOUTH KOREA’s pursuit of an advanced welfare state has always been challenging. Citizens agree with the necessity to build a better social safety net for everyone, but hesitate when it involves a greater financial burden. Such is the case for the recent welfare project of the Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG). The so-called Youth Allowance Project targets the disconnected youth, a recent term brought up by the SMG to describe young people in their twenties who are neither working nor studying at school. However, doubts have arisen about whether the new program can really help these youths with their careers.

A social safety net for the youth

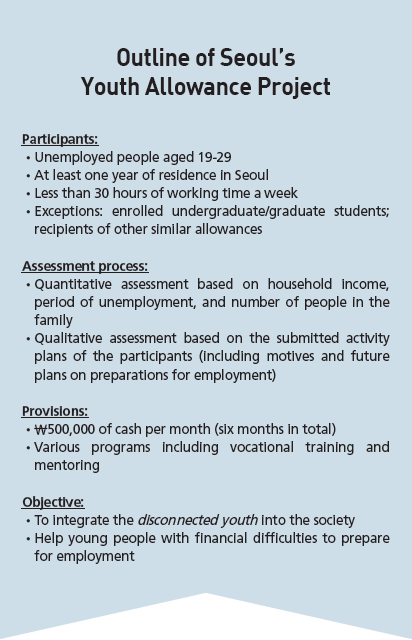

Since Aug. 3, the SMG started to provide a monthly allowance of ₩500,000 for the recipients of the Youth Allowance Project. Requirements for eligibility to receive the allowance are strict, as the program targets middle to lower class people who have financial trouble preparing for employment. Applicants for the allowance have to be between the ages of 19 and 29 and should have resided in Seoul for at least one year, working less than 30 hours a week. Moreover, those who are enrolled in school or are already being provided with other similar allowances from a different city or program are not eligible.

The SMG first went through a quantitative assessment of the applicants based on factors including household income (50%), period of unemployment after graduation (50%), and the number of people in the family (bonus points). Then, it went through a qualitative assessment of the applicants, looking at their plans, motives, and objectives regarding their future activity to seek employment. In the end, more than 6,000 people applied and a total of 3,000 were selected as recipients for the project. The Youth Allowance Project is only a trial, but if it should yield positive results, the SMG plans to expand the number of recipients.

Seoul’s project is conditional; in return for the monthly provisions, the recipients must write a report each month on how they have used their allowances and what activities they have done regarding employment. If they fail to do so, they will receive no subsidy. There is also a monitoring system that regularly checks on the recipients’ cash receipts and expenditure accounts to prevent them from exploiting the allowances for other activities. Further, the Youth Allowance Project does not simply aim to provide benefits for the unemployed youth; it includes various activities such as mentoring, in order to help them receive necessary job information and search for suitable jobs.

The city government’s plan is a response to the high unemployment rate amongst young Koreans. According to Statistics Korea, in February, South Korea’s youth unemployment rate stood at 12.5%, which is a relatively low rate compared to other OECD countries like Spain, France, and Greece. In Korea, however, there is a high number of people preparing for the civil service examinations or those who have given up searching for jobs, and these people are not included in the unemployment rate. “500,000 out of a total 1.44 million people in their twenties living in Seoul are experiencing long-term unemployment or underemployment,” wrote Park Won-soon (Mayor, Seoul Metropolitan Government) on his Facebook. “Young people are our future. If we do not work for them, they will become poor. It is our task to provide a social safety net for the younger generation.” The new project, according to Mayor Park, is a long-term plan to promote more social participation amongst these disconnected youth.

Simmering disputes

As soon as the Youth Allowance Project took off on Aug. 3, the Ministry of Health and Welfare invoked an ex officio cancellation* against the project. The Ministry states that the project violates Article 26 of the Framework Act on Social Security, which states that “in cases of newly establishing or altering a social security system, the heads of relevant central administrative agencies and the heads of local government agencies shall enter into a consultation, as prescribed by the Presidential Decree … with the Ministry of Health and Welfare.” In response, the SMG called for a withdrawal of the ex officio cancellation, citing Article 117 of the Constitution of The Republic of Korea, which states: “Local governments shall deal with administrative matters pertaining to the welfare of local residents, manage properties, and may enact provisions relating to local autonomy, within the limit of Acts and subordinate statutes.” The conflict continues between the central and the local government.

On Aug. 12, the Ministry of Employment and Labor surprisingly announced that it will start providing ₩600,000 in total over three months to low-income, young employment seekers who are taking part in the Employment Success Package. The package was first launched in 2010 to help young adults who have difficulties finding jobs or who only have temporary jobs and are looking for full-time positions. The new program under the Employment Success Package is called the Youth Hope Fund, and targets those aged 18 to 34. Recipients of the program can use the fund only in preparation for job interviews, transportation fees, and rental costs for suits. The Ministry’s program is different from Seoul’s in that the former only focuses on helping young people with job preparations, while the latter concentrates on integrating low-income youths into society. According to Lee Ki-kweon (Minister, Ministry of Employment and Labor) during his announcement at the Seoul Government Complex, “Seoul’s project does not set the youth’s participation in job searching efforts as a precondition.”

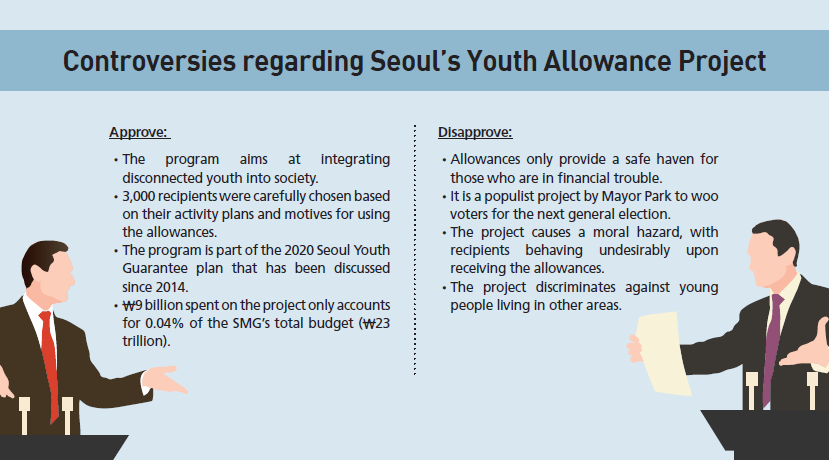

Meanwhile, the public is also divided over the controversial issue of Seoul’s Youth Allowance Project. The main claim of the opponents of the project is that providing allowances to the recipients does not lead to the improvement of youth unemployment. According to Ryu Ki-jung (Director, Korea Employers Federation) at the Korean Tripartite Forum in 2015, “It is difficult to alleviate the youth unemployment rate by sharing money. Youth unemployment originates from the unfair system and practice of the labor market rather than the youth’s financial hardships.” Seoul’s project is not yet specific on how it will help the jobless youth to find employment. The allowances only seem to provide a safe haven for those who are in financial trouble. Kim Jin-seon (Jr., UIC, Dept. of Econ.) also remarked that “there should rather be more discussions on how companies could expand the number of workplaces for young people. I don’t see a clear relation between providing allowance to the youth and helping them with employment.”

Opponents also claim that the project comes with unfavorable causes and consequences. Many criticize Seoul’s project as a populist program by Mayor Park to woo voters for the upcoming general election in 2017. “While I agree that youth unemployment is an important issue that should be solved, purchasing the youth’s minds with allowances is typical populism. Buying voters through welfare tax will definitely result in heavy criticisms from the residents,” stated Kim Moo-sung, the previous Chairman of the Saenuri Party, during a speech at the National Assembly in March. Further, critics claim that the allowance causes a moral hazard, in which the recipient behaves undesirably upon receiving the allowance. For instance, the recipients may start relying more on welfare to support their personal needs, rather than using it to seek employment.

Young people residing outside of Seoul are also dissatisfied with the project. “Seoul’s program discriminates against young people living in other areas. Young people residing in Seoul are not the only youth that needs help,” said an anonymous resident of Incheon during an interview with Dailian. After all, the project only provides for 3,000 people residing in Seoul among thousands of unemployed youth in South Korea. While ₩9 billion is being spent over the six-month project, some suggest that Seoul should rather take specific measures that are related to job preparation, such as provision of fees for language certificates, or for job-preparing academies.

The SMG, on the other hand, argues that the Youth Allowance Project is only a trial, and if it succeeds, other local governments may well follow Seoul’s example. The project, according to the SMG, aims to grant minimum financial support for lower-income young adults who are currently seeking employment. Many have limited time and resources to prepare for jobs. The program is not simply aimed at providing allowances or guaranteeing jobs to the unemployed. It rather attempts to *integrate* those youths with financial difficulties into society, helping them to become more active. Seoul’s project is a proactive program that provides information on employment through mentoring and other activities.

In response to the opponents’ claims about the danger of moral hazard, the SMG stated on its website, “Those who claim that the recipients will act in moral hazard have no faith in the young generation. Rather than criticizing the young people, we must truly listen to their needs and make action.” It further stated, “We carefully chose 3,000 recipients who showed great willingness to use the allowances in searching and preparing for jobs. Recipients must submit a monthly activity report on how they have used their allowances. With our strict monitoring system, there is a low possibility that they will exploit the benefits for other personal needs.”

The SMG also refuted the populist claim, stating that the allowance program has been carefully planned as part of the 2020 Seoul Youth Guarantee plan** that was first announced in 2014. The Youth Allowance Project was the outcome of a total of 23 conferences, forums, and discussions held during the past two years concerning the young generation’s problems. According to the SMG, “the project reflects young people’s voice. Stating that such a project is a populist program of Mayor Park is an exaggeration.”

Similar programs for youth employment

Seoul’s Youth Allowance Project is not the only existing program that addresses youth unemployment. The Municipality of Seongnam has been carrying out a trial program called Youth Dividend since 2015. The program grants ₩250,000 each quarter (₩1,000,000 for a year) to all residents of Seongnam aged 24. After the trial, Seongnam City plans to expand the benefit to all Seongnam residents aged 19 to 24. Recipients of the benefit receive a Seongnam Gift Certificate that can be used as cash in designated areas, including academies, bookstores, restaurants, supermarkets, clothes stores, and hair shops within the city. The ultimate goal of the program is to provide basic income to young people for job preparations and basic living expenses. Seongnam’s program is different from Seoul’s allowance project in that the former grants subsidy to young job seekers regardless of their income, while the latter targets the low income class. Further, Seoul’s project limits the use of the allowance to specific employment-related activities, such as job lessons and transportation. Despite these differences, both programs share the goal of stabilizing youth unemployment.

When Seongnam’s Youth Dividend program first launched in 2015, it faced similar criticisms to Seoul’s project. The opponents’ main claim was that the program was not the fundamental solution to alleviate the high unemployment rate of the young generation. Nevertheless, the satisfaction rate of the program was high. For three days during April 2016, Seongnam’s research institution Southern Post conducted a survey on 2,866 recipients on the satisfaction rate regarding the Youth Dividend program, and 96.3% of the respondents answered that the program was helpful. Moreover, in an interview with Kookmin Ilbo, Lee, one of the recipients’ mother, said, “My son is graduating college next year, and he is collecting the subsidies provided by Seongnam’s Youth Dividend program. He is planning to buy books to prepare for his career.” The Municipality of Seongnam plans to continue the program in the long-term.

France also carries out a project called La Garantie Jeunes (Youth Guarantee) which grants benefits to unemployed people between ages 18 and 25. It provides €452 per month to those whose monthly income does not exceed the minimum welfare benefit of €499.31 provided by the Revenu de solidarité active (RSA). The program focuses on integrating the young NEETs (not in employment, education or training) into the society and increasing their chances in the labor market, providing them with work experience, training, and financial support. It expects recipients to get employed within three to six months of provision. By 2017, 100,000 to 150,000 people are expected to benefit from the program.

The program is significant in that it creates a safety net for socially neglected youth. According to 2016 Employment Outlook, a report by the OECD, the Youth Guarantee represents a “significant commitment to help disadvantaged youth find sustainable employment.” The methods taken by the program, such as counseling, job search assistance, and job readiness training, have all proved successful in other OECD countries. The French program came along with positive feedback from the recipients as well. Marina, one of the participants in the program, commented during an interview with the Ministry of Employment, “The Youth Guarantee made me realize that I am not the only one suffering.”

Although the French program is yet to alleviate the high unemployment rate of young people in France, the project is expected to yield positive results in the long-term; it also holds a symbolic meaning in providing a *chance* for the jobless youth. This should be enough inspiration for Seoul to carry on its project despite the current harsh criticisms.

* * *

Both Seoul’s and Seongnam’s projects are subject to the same criticism that the programs do not aim to alleviate the youth unemployment crisis. In order to prove that Seoul’s new project is not simply a financial provision to the needy, the SMG must come up with a variety of employment-related services, such as vocational training and counseling. It should also lay out specific measures and plans on how its project will support the recipients to integrate into the society and economy over the six-month course. If many of the 3,000 recipients should later prove that the allowances really helped them to prepare for jobs, then Mayor Park may be able defuse criticism of the project.

*Ex officio cancellation: It refers to the power granted to a public office which can use its institutional authority to cancel a certain system or program.

**2020 Seoul Youth Guarantee plan: Planned since 2014 and officially launched in November 2015, the five-year program aims to provide ₩500,000 per month to 5,000 young, unemployed people by 2020. It focuses on four different areas, including funding for social participation activities, jobs, housing, and spaces for social activities.

Yeo Ye-rim

yryeo94@yonsei.ac.kr