An insight to barrier-free arts on university campuses

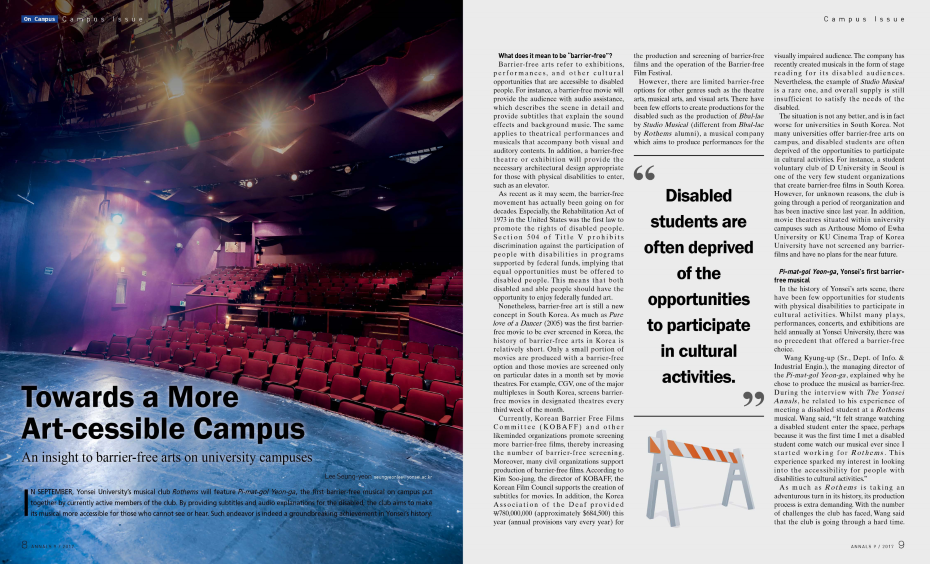

IN SEPTEMBER, Yonsei University’s musical club Rothems, will feature Pi-mat-gol Yeon-ga, the first barrier-free musical on campus put together by currently active members of the club. By providing subtitles and audio explanations for the disabled, the club aims to make its musical more accessible for those who cannot see or hear. Such endeavor is indeed a groundbreaking achievement in Yonsei’s history.

What does it mean to be “barrier-free”?

Barrier-free arts refer to exhibitions, performances, and other cultural opportunities that are accessible to disabled people. For instance, a barrier-free movie will provide the audience with audio assistance, which describes the scene in detail and provide subtitles that explain the sound effects and background music. The same applies to theatrical performances and musicals that accompany both visual and auditory contents. In addition, a barrier-free theatre or exhibition will provide the necessary architectural design appropriate for those with physical disabilities to enter, such as an elevator.

As recent as it may seem, the barrier-free movement has actually been going on for decades. Especially, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 in the United States was the first law to promote the rights of disabled people. Section 504 of Title V prohibits discrimination against the participation of people with disabilities in programs supported by federal funds, implying that equal opportunities must be offered to disabled people. This means that both disabled and able people should have the opportunity to enjoy federally funded art.

Nonetheless, barrier-free art is still a new concept in South Korea. As much as Pure love of a Dancer (2005) was the first barrier-free movie to be ever screened in Korea, the history of barrier-free arts in Korea is relatively short. Only a small portion of movies are produced with a barrier-free option and those movies are screened only on particular dates in a month set by movie theatres. For example, CGV, one of the major multiplexes in South Korea, screens barrier-free movies in designated theatres every third week of the month.

Currently, Korean Barrier Free Films Committee (KOBAFF) and other likeminded organizations promote screening more barrier-free films, thereby increasing the number of barrier-free screening. Moreover, many civil organizations support production of barrier-free films. According to Kim Soo-Jung, the director of KOBAFF, the Korean Film Council supports the creation of subtitles for movies. In addition, the Korea Association of the Deaf provided 780,000,000 (approximately $684,500) this year (annual provisions vary every year) for the production and screening of barrier-free films and the operation of the Barrier-free Film Festival.

However, there are limited barrier-free options for other genres such as the theatre arts, musical arts, and visual arts. There have been few efforts to create productions for the disabled such as the production of Bbal-lae by Studio Musical (different from Bbal-lae by Rothems alumni), a musical company which aims to produce performances for the visually impaired audience. The company has recently created musicals in the form of stage reading for its disabled audiences. Nevertheless, the example of Studio Musical is a rare one, and overall supply is still insufficient to satisfy the needs of the disabled.

The situation is not any better, and is in fact worse for universities in South Korea. Not many universities offer barrier-free arts on campus, and disabled students are often deprived of the opportunities to participate in cultural activities. For instance, a student voluntary club of D University in Seoul is one of the very few student organizations that create barrier-free films in South Korea. However, for unknown reasons, the club is going through a period of reorganization and has been inactive since last year. In addition, movie theatres situated within university campuses such as Arthouse Momo of Ewha University or KU Cinema Trap of Korea University have not screened any barrier-films and have no plans for the near future.

Pi-mat-gol Yeon-ga, Yonsei’s first barrier-free musical

In the history of Yonsei’s arts scene, there have been few opportunities for students with physical disabilities to participate in cultural activities. Whilst many plays, performances, concerts, and exhibitions are held annually at Yonsei University, there was no precedent that offered a barrier-free choice.

Wang Kyung-up (Sr., Dept. of Info. & Industrial Engin.), the managing director of the Pi-mat-gol Yeon-ga, explained why he chose to produce the musical as barrier-free. During the interview with The Yonsei Annals, he related to his experience of meeting a disabled student at a Rothems musical. Wang said, “It felt strange watching a disabled student enter the space, perhaps because it was the first time I met a disabled student come watch our musical ever since I started working for Rothems. This experience sparked my interest in looking into the accessibility for people with disabilities to cultural activities.”

As much as Rothems is taking an adventurous turn in its history, its production process is extra demanding. With the number of challenges the club has faced, Wang said that the club is going through a hard time. The employment of new facilities is one of the largest tasks Rothems is to overcome. Especially, the Closed Caption (CC) system differentiates Pi-mat-gol Yeon-ga from the previous productions. The CC system provides its services through a device or mobile phone applications. Using the given device or their phones, the audience member will have individual access to subtitles and audio explanations. Rothems is currently working on creating Korean subtitles, English subtitles, and audio narrations for the audience.

Moreover, barrier-free productions are expensive to make, especially for student productions. Wang mentioned that the production of Pi-mat-gol Yeon-ga takes around 35,000,000. For Rothems, financing was among the toughest problems it faced. The production of Bbal-lae, a barrier-free musical produced by Rothems alumni in March, was particularly detrimental to Rothems’ budget situation. Since Rothems wanted the musical to be open for as many disabled audience members as possible, the club offered the musical for free, but the consequences were severe. The total cost of the production surpassed its budget by 15,000,000, which is a substantial sum of money for a student club.

However, despite such financial difficulties, Bbal-lae was successful. From a collection of anonymous comments left by audience members after the performance, a majority of the comments remarked how the barrier-free performance was an exceptional experience. Comments left by visually impaired audience members included, “I hope opportunities like this happen more often,” and “It was nice to enjoy a performance with able students.” Comments left by auditorily impaired audience members included, “I liked the subtitles. Although I could not hear the music, I could feel it in my heart,” and “I have always wanted to watch musicals, and I am so happy for this opportunity.”

Therefore, Rothems was determined to once again make their musical accessible to students who once were ostracized from the cultural scene. In order to overcome the financial challenges for the production, the club is currently cooperating with several companies to put on the show. Wang remarked that Rothems had never cooperated with this many companies in its history. For instance, Rothems is currently raising funds through Kakao’s social contributory platform called Gat-ie-Ga-chi with Kakao for its budget. The platform is holding a project called “King of Volunteer, That is Me” which provides an opportunity for voluntary projects to raise funds. Through this fundraising project, Rothems’ production of Pi-mat-gol Yeon-ga aims to raise 5,000,000. Also, Rothems has collaborated with Sil-lo-am Welfare Center for Visually Impaired People in publishing Braille brochures for the musical and creating a social campaign for increased awareness of the blind. Not to mention, it has also received funding from a number of patrons in order to cover its expenses.

Wang added that he has been asking the Office of Student Welfare Services for budgetary support. Since the university does not provide any financial support for student extracurricular organizations, chances are very low. However, support from school would mean a lot because Pi-mat-gol Yeon-ga is not a mere school production but a social contribution for the increased accessibility of the arts. Wang said, “Spending our time and effort on creating the narrations and subtitles for the musical instead of preparing for the budget would definitely improve the quality of the musical for those who were once neglected of their cultural rights.”

Barrier-free arts and the student society

According to Kim Soo-jung, barrier-free arts have become widely adopted by many artists in foreign countries. In a theatre Kim visited in Australia, audience members in need of barrier-free services could apply for the necessary service in advance. Following their orders, the theatre provided them with a receiver through which they could directly read the descriptions. Moreover, there are aquariums or art exhibitions that incorporate a service that allows the visually impaired to understand the art by touching the 3D copies of the exhibits. Museo Del Prado of Spain is a leading example — its recent exhibition Touching the Prado has incorporated six touchable copies of its paintings and audio explanations for the visually impaired.

While the current legislation of Korea prohibits the discrimination against persons with disabilities, it does not specify that arts and performances should have barrier-free options. Therefore, even though federally funded galleries or productions do not offer a barrier-free option for the disabled, there is no associated penalty. Artists or producers do not find it necessary to spend additional costs of providing barrier-free options. The law exists under the name of “Anti-Discrimination Against and Remedies for Persons with Disabilities Act and Enforcement Decree”, but it is questionable as to whether it sincerely functions to prohibit “discrimination” against the disabled and promote equal rights of all citizens, regardless of their disability. In order to preserve the disabled of their cultural rights, these social norms must be challenged.

Kim reinforced that it is important for students to challenge such norms because they have the potential to bring about change. Students could either start a social campaign to increase awareness or provide barrier-free cultural opportunities. As much as universities are where students can be experimental and bold, Kim hopes to see university students take the lead in social changes. The disabled deserve to enjoy equal opportunities, and it is of an important duty for students, as future artists, producers, and pioneers, to ensure them of their basic cultural rights.

* * *

As the large attention provoked by the production of Pi-mat-gol Yeon-ga proves, barrier-free performances are commonly perceived as an extraordinary and uncommon experience. Although it is a good sign that more barrier-free performances are produced in Korea, barrier-free elements should be employed in all cultural experiences for the disabled to enjoy the arts like the able audience. Disability should not deny the disabled of artistic sensibility, and it should not deprive the disabled of their rights to cultural experiences and nourishment.

Pi-mat-gol Yeon-ga, hitting the theatre of the Centennial Hall from September 4th – 7th, will be accessible for all students. Tickets for the show are available on (goo.gl/AJrgvu), and more information on the upcoming musical is available on Rothems’ Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/yonseimusical). Since the opportunity to watch a barrier-free musical on campus does not come so often, it is highly recommended that Yonseians come watch Pi-mat-gol Yeon-ga.

Lee Seung-yeon

seungyeonlee@yonsei.ac.kr