Dissecting the culture of shame and secrecy behind the stigmatization of menstruation

THE NATURAL cycle of the life on earth grants many things in our world: the rise and fall of the sun, the birth and death of organisms, the ebb and flow of the seas, and…menstruation. Equally as natural as the cycle of the heavens, the workings of the ecosystem and the movement of the waters is female menstruation. Despite its perfectly natural state of being, however, menstruation has long been regarded as an inappropriate matter for public discussion. Seen as the symbol of impurity and contamination, menstruation stands with a long history of neglect and disdain. Even to this day, the topic remains an indelicate subject—even a societal taboo—in many nations. How has this bizarre culture of shame and secrecy come about, and how is it undergoing change in the contemporary world?

Defining the problem

Let’s begin with the golden question—what is menstruation? A biological process within a woman’s reproductive cycle, menstruation refers to the discharge of the uterus lining, which thickens each month in preparation for a woman’s pregnancy that occurs to a non-pregnant woman on a monthly interval. This biological phenomenon is an inseparable daily routine to all women; almost as natural and due in course as is going to the toilet and digesting food.

We normally assume the frequency and regularity of something would be directly proportional to its level of familiarity and acceptance within the society. The more people experience the matter, surely the more they would be willing to talk about it, right? This easily accepted assumption, however, faces a compelling counterexample when applied to the case of menstruation. As much as it is a natural and routine part of the life of any woman (who, for your information, make up half of the world’s population), it is powerfully concealed and even suppressed in many, if not all, societies.

An analysis of the past reflects how the humanity’s failure to take this recurring biological process of the female anatomy at face value has been a continuous historical phenomenon. The negative interpretation and response to menstruation appears to have continued across history and across continents in perpetuum. How so? How did this stigmatization come to reign our society?

The answer lies in religion, tradition, and culture: the three of the most essential pillars that form the basic values of a being. For hundreds of years, these essential components, those which shape the people’s ways of life, have been rendering the matter of menstruation so tricky for so many.

With the most dominant religions—Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism—viewing menstruation as a punishment from God, it is with no surprise that the “bleeding shame” has been the dominant concept among the public for centuries of time. Many religions even stipulate restrictions concerning the “right” societal attitude towards a menstruating woman.

Judaism, for instance, brands menstruation as “ritually unclean” and sets out a rule of conduct in response. According to Aru Bhartiya’s study in 2013, “Menstruation, Religion and Society,” the Book of Leviticus specifies that “If a woman has an emission, and her emission in her flesh is blood, she shall be seven days in her [menstrual] separation, and anyone who touches her shall be *tamei* [interpreted as ritually unclean commonly by people] until evening...And if any man lie with her at all and her [menstrual] separation will be upon him, he will be *tamei* for seven days."

As can be clearly seen from this case, the stigmatization of menstruation lies deep within religious grounds. Accordingly, numerous traditions and cultures have come to associate menstruation with negative concepts of impurity and contamination, due to the influence of such religious beliefs. According to *Sikhism: An Introduction* by Nikky-Guninder Kaur Kaur Singh, even *Mahatma* (Sanskrit for “venerable”, or “high-souled”—*The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary*) Gandhi is known to have regarded menstruation as an indicator of a woman’s distorted soul, and believed that she would stop menstruating only when her soul had become purified.

The status quo

It is not difficult to infer from these individual cases the entire history of ignominy, concealment, and suppression that women had to endure for centuries. A simple examination of the status quo proves that this mindset of the bleeding shame has persisted into the contemporary times. Consider the case of Korea, for instance. The culture governs every aspect of a woman’s life: it persists in the general language of the public, it persists in the media, and it persists in the daily activities of an average citizen.

An entire dictionary of metaphors exists to replace the word “menstruation” with “magic day,” “the day of mother nature,” and “that day” being particular favorites of many Koreans. Such euphemisms have taken over the idiosyncrasies of the public, a trend that has not been exclusive to Korea: according to *Hankookilbo*, researchers estimate that approximately 5,000 euphemisms exist in replacement of the word “menstruation” all across the globe. Just as the magical society in J.K Rowling’s best seller novel *Harry Potter* dreads to utter the name of the evil wizard, Voldemort (or “he who must not be named”), so too does our society in saying menstruation aloud.

Furthermore, this culture of period shaming continues to perpetuate through the Korean media. Advertisements of sanitary pads, for instance, ironically never contain the word “menstruation,” or even “sanitary pad.” Instead, they are once again evaded in vague terms, or replaced by a metaphor. This once again reflects the culture of suppression: even when the matter of menstruation is openly discussed on the surface, it is never quite done in a direct and straight-forward manner.

Moreover, these commercials usually appear in a perfectly set-up background that screams “purity” and “cleanliness” as if those were “God-sent” conditions to live by. The fact that such media portrayals of female menstruation do not allow a single speck of dust reflects the hidden fear of impurity and uncleanliness that the society seems to have preserved from the old times.

Another way the culture of shame and secrecy manifests in the Korean society is through the very way individuals act in their daily lives. The epitome of this is the Korean cashiers’ tendency to pack sanitary pads in a black plastic bag. When a customer purchases sanitary pads in stores, it is considered good manners on the cashier’s part if he or she puts it in a black plastic bag so that the pad cannot be seen by others.

In addition, when girls pass on sanitary pads or tampons to each other, they suddenly become 007 agents: smuggling the pad through their shirt sleeves, or exchanging tampons under the desk in a secretive way so that no one can dare notice this top-secret transaction.

A social experiment by Dotface, a Korean media startup based on video journalism, in 2016 reflect how commonplace this practice is. Members of Dotface went out on the streets, visited numerous convenience stores and recorded how many returned the sanitary pads in a black plastic bag. It revealed that an overwhelming majority—except the ones that ran out of black plastic bags—returned the favor.

When asked the question─“why do you put the pads in a black bag when you give them back to the customers?”─the cashiers replied, “because the pads can see through if the bag is not black,” “because it is a little embarrassing,” and “so that the others do not know what is in the bag.” Under these responses lie the assumption that the customers must undoubtedly feel ashamed about their purchase of the female hygiene products.

The question now is, is this culture of “bleeding shame” specific only to Korea? The answer is a loud and clear “no.” The secrecy and shame associated with menstruation appears to be a universal phenomenon, even in nations that are considered to be at the forefront of a liberal mindset. For instance, in 2012, the renowned pop star Christian Aguilera appeared on stage with clear stains of menstrual blood on her legs. The photograph of this scene caused an uproar online, with the media and the public labelling it as embarrassing, gross and shameful.

However, recently a wave of change has been sweeping over this traditional attitude that diminishes menstruation from the natural bodily function it is. This wave first started when women began to question the norms that were placed upon them. Why is it that something so natural as the matter of female hygiene became a subject of taboo?

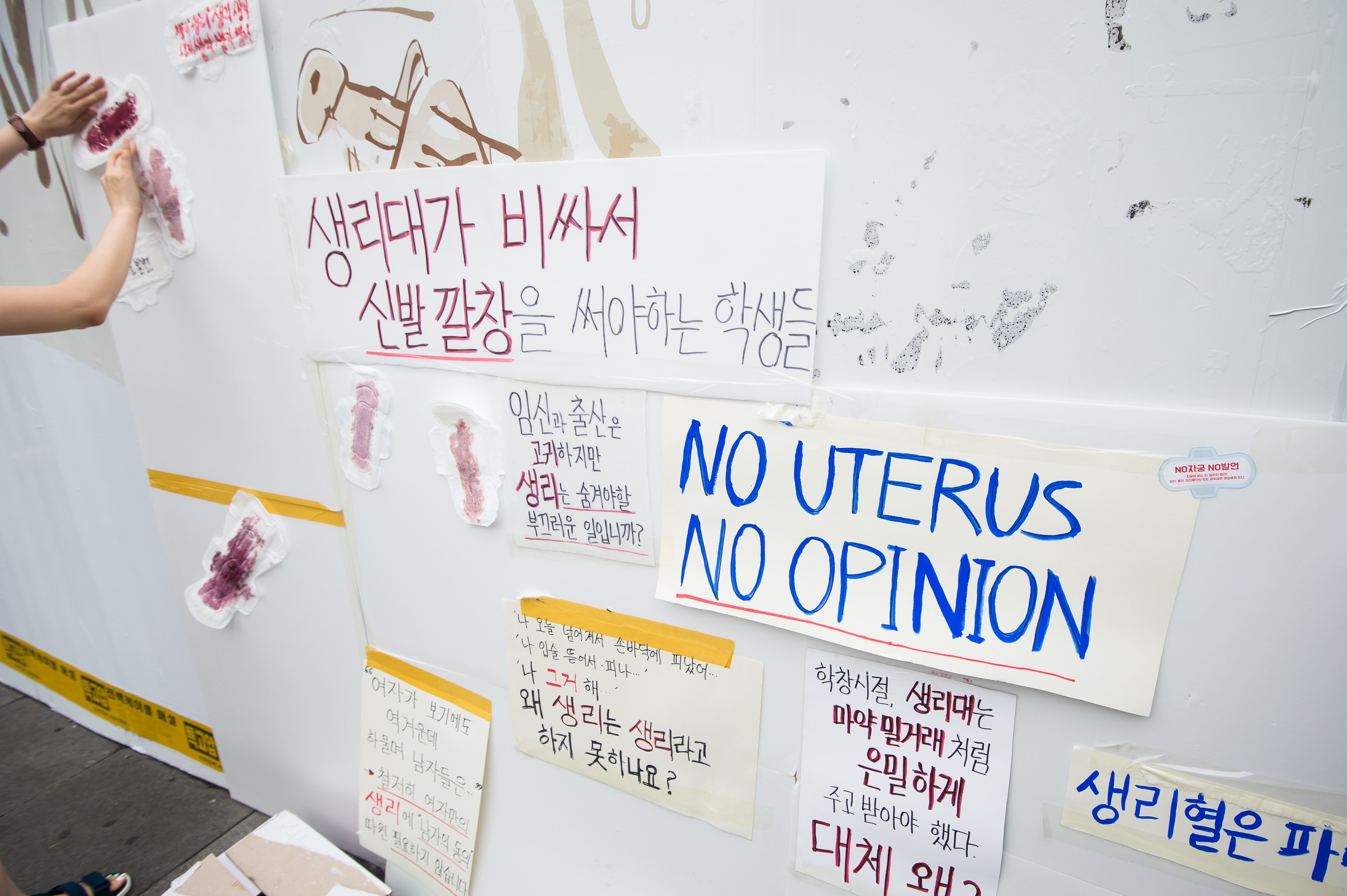

The voices demanding change has been on a constant rise, with both individuals and groups actively seeking to bring fundamental transformation to the social stigma. In 2016, a group of female activists came together in Insadong to promote their campaign that calls for a conversion in the society’s negative recognition of menstruation. They stuck sanitary pads up on the walls, posted placards criticizing the traditional suppression of menstruating women, and demanded the shift in individual attitudes towards menstruation. This campaign soon became a platform for public engagement. Pedestrians and interested parties joined in the campaign, adding their own opinion to the issue.

Similarly, individuals have also been actively participating in this social campaigning for the unveiling of menstruation in Korea. A trend among YouTubers, for instance, has been moving on from the reviews of makeup products and clothing lines to the reviews of female hygiene products. From reviews of various sanitary pad brands and tampons to those of menstrual cups—a novel invention that has been on a rising influx to Korea—a number of Korean YouTubers have been breaking the taboo in their own ways, through their own platforms and skillsets.

From a social taboo to now a common discussion material in households, schools, and the media, menstruation has made a long way through its long history. However, there still exists a vast room for progress, in order for such shift in attitudes to become a society-wide phenomenon. It is time to take menstruation at face value, for what it really is: a natural phenomenon of the female anatomy. Because it is about bloody time.