Taking the Peace Train to the world’s one and only Demilitarized Zone

ISSUES CONCERNING the division of the two Koreas and their reunification have always been unapproachable for me, as I lived abroad throughout my adolescence. I was oblivious to the inerasable scars that the division had left on Koreans, and its tremors still reverberating throughout the contemporary society. However, the repercussions of the separation struck me recently after watching a heartbreaking video on the reunion and almost immediate separation of family members from North and South Korea; these families were sobbing at the fact that they are unlikely to see each other again in the foreseeable future. Realizing the need to understand the tragic remnants of the past, I booked a ticket for the One-Day Mt. Dora Security Tour, a package tour that introduces historically important spots around Mt. Dora.

The Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) is known as the Korean Demilitarized Zone abroad because it is singular to the Korean Peninsula—the only divided country in the world. The DMZ is an area where the stationing of forces, placement of weaponry, and installation of military facilities have been banned after the Korean Armistice Agreement*. According to NASA Earth Observatory, the DMZ is 250 kilometers long and 4 kilometers wide, intersecting with, but not necessarily following, the 38th parallel. The part of the DMZ I decided to visit was an area around Mt. Dora Station in Paju, Gyeonggi-do.

My journey to the DMZ began with boarding the DMZ Peace Train at 10 a.m. at Yongsan Station. Recognizing the Peace Train was hardly a difficult task. It has a distinct appearance, marked by numerous roses of Sharon, the national flower of Korea. Also, there were decorations of characters dressed in traditional red and blue costumes to symbolize a unified Korea. Walking inside, my immediate thought was: “Oh, my youngest sister would like this.” The interior of the train was overly flamboyant, including seats patterned with colorful pinwheels. I found myself perplexed and amused by the light-hearted atmosphere of the train compared to the weight of its destination. What was especially memorable was the slow speed of the train; Peace Trains are all Sae-ma-eul Trains, meaning they are considerably slower than the KTX express trains. The calm speed, however, allowed me to fully enjoy the peaceful, tranquil view of the outskirts of Seoul. As the train was passing by the Imjin River, the only river that flows across both Koreas, the train began to play “A-ri-rang,” a traditional Korean folk song. The song stirred a solemn feeling in me upon realizing that when the song had first been composed, the Koreas were yet united, and division would have been unimaginable.

The Peace Train stopped at the Imjin River Station for an identity check after an hour-long ride. Within ten kilometers from the Military Demarcation Line (MDL) or the ceasefire line, there is a Civilian Control Line (CCL)**, where the entrance of civilians is strictly supervised due to possible military dangers. Thus, those on the Peace Train must go through identity checks, which involve showing ID cards and submitting applications for entrance. Receiving hard, almost intimidating stares from the soldiers who oversaw identity checks, I began to sense the gravity of entering a potentially dangerous area.

Following the identity check, passengers (including myself) climbed onto the train again to reach the final destination, Mt. Dora Station. Arriving at Mt. Dora Station, we boarded the tour bus, where the guide began the tour by warning us that we were entering the Civilian Control Zone from this point on, and taking photos in the street was prohibited. Afterwards, we were introduced to a tollgate nearby: it is the only tollgate to the other Korea and vice versa, so government officials use it when they meet for talks. The tollgate reminded me of the movie Steel Rain in which after a coup, the North Korean leader escapes to South Korea via a tollgate with the main character played by Jung Woo-sung. The movie seems to have well portrayed the tollgate and its surrounding areas.

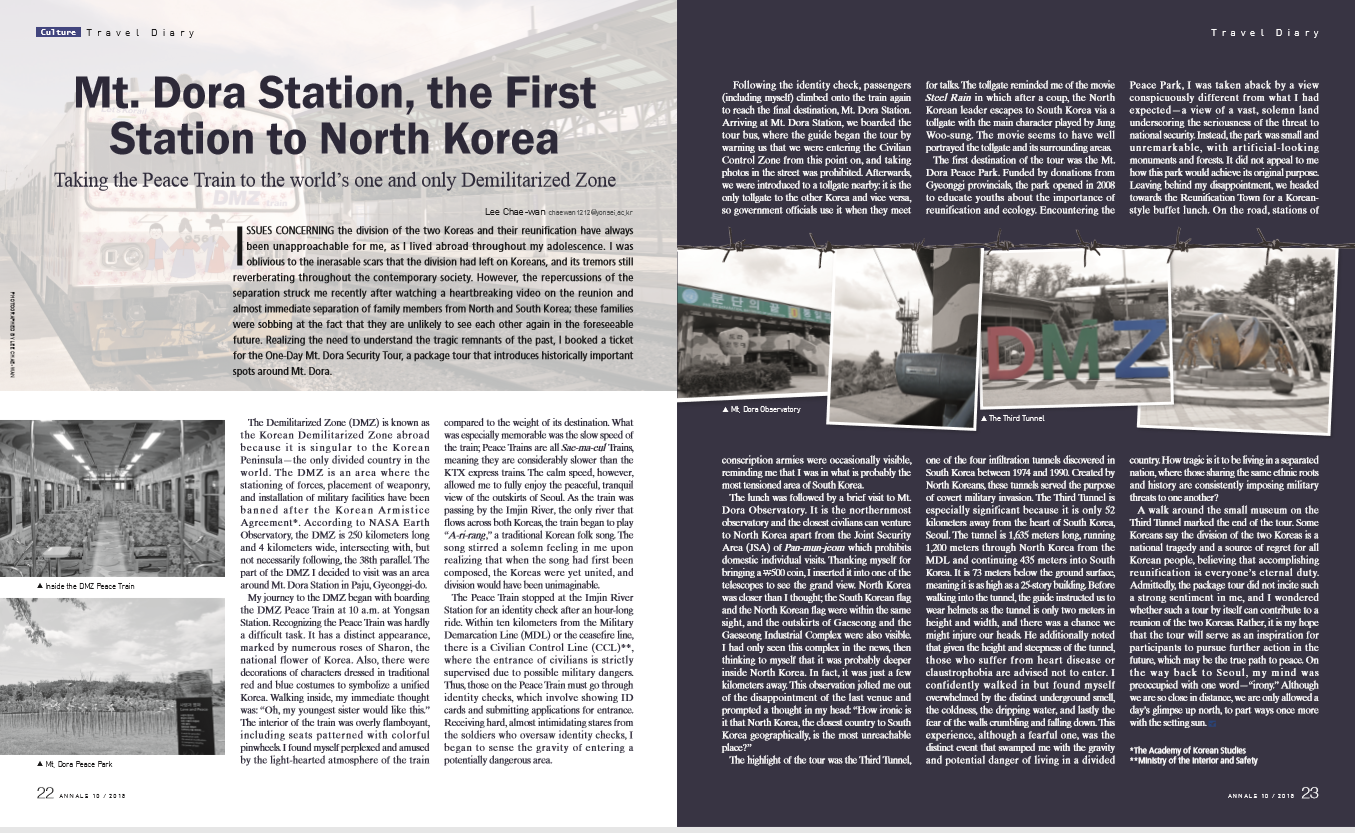

The first destination of the tour was the Mt. Dora Peace Park. Funded by donations from Gyeonggi provincials, the park opened in 2008 to educate youths about the importance of reunification and ecology. Encountering the Peace Park, I was taken aback by a view conspicuously different from what I had expected—a view of a vast, solemn land underscoring the seriousness of the threat to national security. Instead, the park was small and unremarkable, with artificial-looking monuments and forests. It did not appeal to me how this park would achieve its original purpose. Leaving behind my disappointment, we headed towards the Reunification Town for a Korean-style buffet lunch. On the road, stations of conscription armies were occasionally visible, reminding me that I was in what is probably the most tensioned area of South Korea.

The lunch was followed by a brief visit to Mt. Dora Observatory. It is the northernmost observatory and the closest civilians can venture to North Korea apart from the Joint Security Area (JSA) of Pan-mun-jeomwhich prohibits domestic individual visits. Thanking myself for bringing a ₩500 coin, I inserted it into one of the telescopes to see the grand view. North Korea was closer than I thought; the South Korean flag and the North Korean flag were within the same sight, and the outskirts of Gaeseong and the Gaeseong Industrial Complex were also visible. I had only seen this complex in the news, then thinking to myself that it was probably deeper inside North Korea. In fact, it was just a few kilometers away. This observation jolted me out of the disappointment of the last venue and prompted a thought in my head: “How ironic is it that North Korea, the closest country to South Korea geographically, is the most unreachable place?”

The highlight of the tour was the Third Tunnel, one of the four infiltration tunnels discovered in South Korea between 1974 and 1990. Created by North Koreans, these tunnels served the purpose of covert military invasion. The Third Tunnel is especially significant because it is only 52 kilometers away from the heart of South Korea, Seoul. The tunnel is 1,635 meters long, running 1,200 meters through North Korea from the MDL and continuing 435 meters into South Korea. It is 73 meters below the ground surface, meaning it is as high as a 25-story building. Before walking into the tunnel, the guide instructed us to wear helmets as the tunnel is only two meters in height and width, and there was a chance we might injure our heads. He additionally noted that given the height and steepness of the tunnel, those who suffer from heart disease or claustrophobia are advised not to enter. I confidently walked in but found myself overwhelmed by the distinct underground smell, the coldness, the dripping water, and lastly the fear of the walls crumbling and falling down. This experience, although a fearful one, was the distinct event that swamped me with the gravity and potential danger of living in a divided country. How tragic is it to be living in a separated nation, where those sharing the same ethnic roots and history are consistently imposing military threats to one another?

A walk around the small museum on the Third Tunnel marked the end of the tour. Some Koreans say the division of the two Koreas is a national tragedy and a source of regret for all Korean people, believing that accomplishing reunification is everyone’s eternal duty. Admittedly, the package tour did not incite such a strong sentiment in me, and I wondered whether such a tour by itself can contribute to a reunion of the two Koreas. Rather, it is my hope that the tour will serve as an inspiration for participants to pursue further action in the future, which may be the true path to peace. On the way back to Seoul, my mind was preoccupied with one word—“irony.” Although we are so close in distance, we are only allowed a day’s glimpse up north, to part ways once more with the setting sun.

*The Academy of Korean Studies

**Ministry of the Interior and Safety

Lee Chae-wan

chaewan1212@yonsei.ac.kr