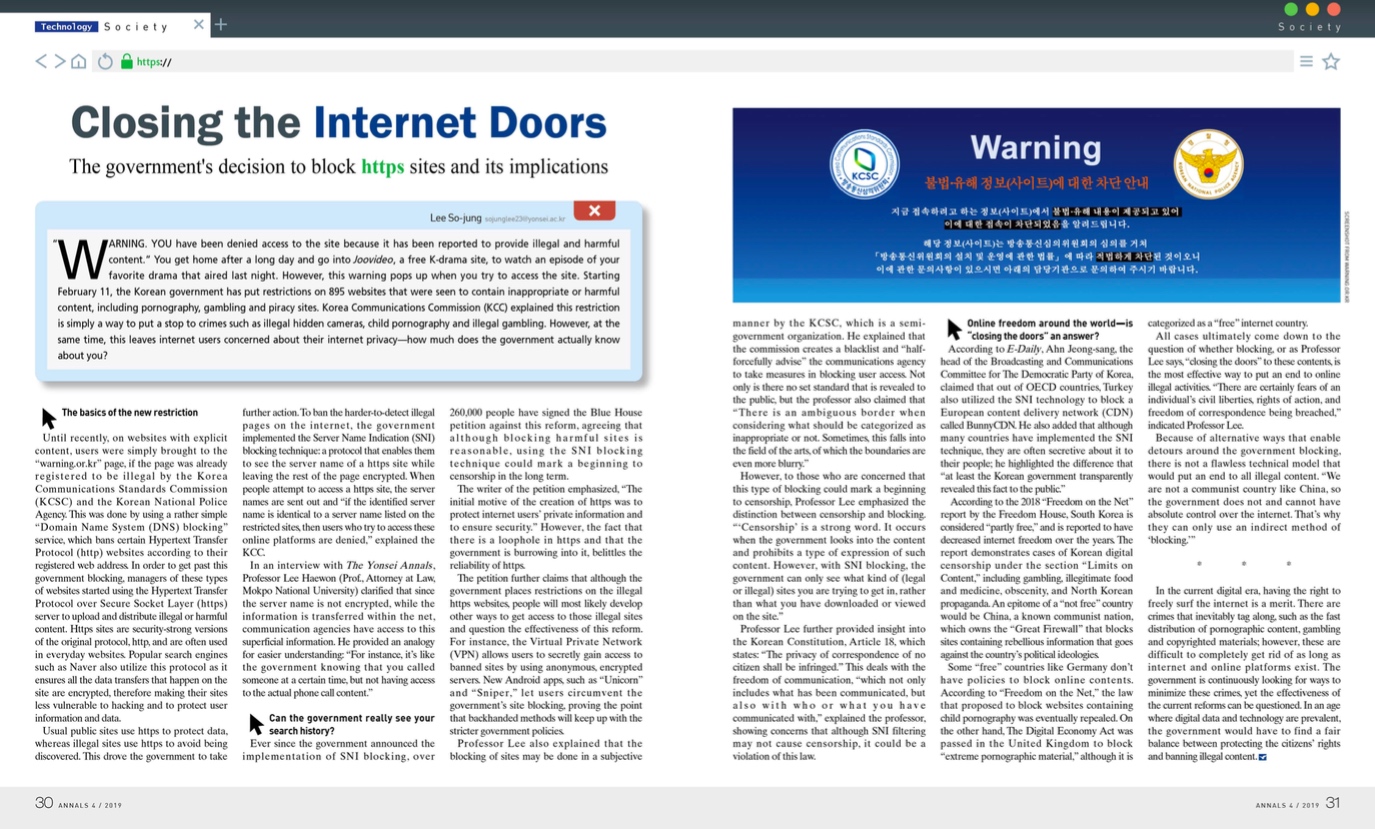

“WARNING. YOU have been denied access to the site because it has been reported to provide illegal and harmful content.” You get home after a long day and go into Joovideo, your favorite free K-drama site, to watch an episode of your favorite drama that aired last night. However, this warning pops up when you try to access the site. Starting February 11, the Korean government has put restrictions on 895 websites that were seen to contain inappropriate or harmful content, including pornography, gambling and piracy sites. Korea Communications Commission (KCC) explained this restriction is simply a way to put a stop to crimes such as illegal hidden cameras, child pornography and illegal gambling. However, at the same time, this leaves internet users concerned about their internet privacy—how much does the government actually know about you?

The basics of the new restriction

Until recently, on websites with explicit content, users were simply brought to the “warning.or.kr” page, if the page was already registered to be illegal by the Korea Communications Standards Commission (KCSC) and the Korean National Police Agency. This was done by using a rather simple “Domain Name System (DNS) blocking” service, which bans certain Hypertext Transfer Protocol (http) websites according to their registered web address. In order to get past this government blocking, managers of these types of websites started using the Hypertext Transfer Protocol over Secure Socket Layer (https) server to upload and distribute illegal or harmful content. Https sites are security-strong versions of the original protocol, http, and are often used in everyday websites. Popular search engines such as Naver also utilize this protocol as it ensures all the data transfers that happen on the site are encrypted, therefore making their sites less vulnerable to hacking and to protect user information and data.

Usual public sites use https to protect data, whereas illegal sites use https to avoid being discovered. This drove the government to take further action. To ban the harder-to-detect illegal pages on the internet, the government implemented the Server Name Indication (SNI) blocking technique: a protocol that enables them to see the server name of a https site while leaving the rest of the page encrypted. When people attempt to access a https site, the server names are sent out and “if the identified server name is identical to a server name listed on the restricted sites, then users who try to access these online platforms are denied,” explained the KCC.

In an interview with The Yonsei Annals, Professor Lee Haewon (Prof., Attorney at Law, Mokpo National University) clarified that since the server name is not encrypted, while the information is transferred within the net, communication agencies have access to this superficial information. He provided an analogy for easier understanding: “For instance, it’s like the government knowing that you called someone at a certain time, but not having access to the actual phone call content.”

Can the government really see your search history?

Ever since the government announced the implementation of SNI blocking, over 260,000 people have signed the Blue House petition against this reform, agreeing that although blocking harmful sites is reasonable, using the SNI blocking technique could mark a beginning to censorship in the long term.

The writer of the petition emphasized, “The initial motive of the creation of https was to protect internet users’ private information and to ensure security.” However, the fact that there is a loophole in https and that the government is burrowing into it, belittles the reliability of https.

The petition further claims that although the government places restrictions on the illegal https websites, people will most likely develop other ways to get access to those illegal sites and question the effectiveness of this reform. For instance, the Virtual Private Network (VPN) allows users to secretly gain access to banned sites by using anonymous, encrypted servers. New Android apps, such as “Unicorn” and “Sniper,” let users circumvent the government’s site blocking, proving the point that backhanded methods will keep up with the stricter government policies.

Professor Lee also explained that the blocking of sites may be done in a subjective manner by the KCSC, which is a semi-government organization. He explained that the commission creates a blacklist and “half-forcefully advise” the communications agency to take measures in blocking user access. Not only is there no set standard that is revealed to the public, but the professor also claimed that “There is an ambiguous border when considering what should be categorized as inappropriate or not. Sometimes, this falls into the field of the arts, of which the boundaries are even more blurry.”

However, to those who are concerned that this type of blocking could mark a beginning to censorship, Professor Lee emphasized the distinction between censorship and blocking. “‘Censorship’ is a strong word. It occurs when the government looks into the content and prohibits a type of expression of such content. However, with SNI blocking, the government can only see what kind of (legal or illegal) sites you are trying to get in, rather than what you have downloaded or viewed on the site.”

Professor Lee further provided insight into the Korean Constitution, Article 18, which states: “The privacy of correspondence of no citizen shall be infringed.” This deals with the freedom of communication, “which not only includes what has been communicated, but also with who or what you have communicated with,” explained the professor, showing concerns that although SNI filtering may not cause censorship, it could be a violation of this law.

Online freedom around the world—is “closing the doors” an answer?

According to E-Daily, Ahn Jeong-sang, the head of the Broadcasting and Communications Committee for The Democratic Party of Korea, claimed that out of OECD countries, Turkey also utilized the SNI technology to block a European content delivery network (CDN) called BunnyCDN. He also added that although many countries have implemented the SNI technique, they are often secretive about it to their people; he highlighted the difference that “at least the Korean government transparently revealed this fact to the public.”

According to the 2018 “Freedom on the Net” report by the Freedom House, South Korea is considered “partly free,” and is reported to have decreased internet freedom over the years. The report demonstrates cases of Korean digital censorship under the section “Limits on Content,” including gambling, illegitimate food and medicine, obscenity, and North Korean propaganda. An epitome of a “not free” country would be China, a known communist nation, which owns the “Great Firewall” that blocks sites containing rebellious information that goes against the country’s political ideologies.

Some “free” countries like Germany don’t have policies to block online contents. According to “Freedom on the Net,” the law that proposed to block websites containing child pornography was eventually repealed. On the other hand, The Digital Economy Act was passed in the United Kingdom to block “extreme pornographic material,” although it is categorized as a “free” internet country.

All cases ultimately come down to the question of whether blocking, or as Professor Lee says, “closing the doors” to these contents, is the most effective way to put an end to online illegal activities. “There are certainly fears of an individual’s civil liberties, rights of action, and freedom of correspondence being breached,” indicated Professor Lee.

Because of alternative ways that enable detours around the government blocking, there is not a flawless technical model that would put an end to all illegal content. “We are not a communist country like China, so the government does not and cannot have absolute control over the internet. That’s why they can only use an indirect method of ‘blocking.’”

* * *

In the current digital era, having the right to freely surf the internet is a merit. There are crimes that inevitably tag along, such as the fast distribution of pornographic content, gambling and copyrighted materials; however, these are difficult to completely get rid of as long as internet and online platforms exist. The government is continuously looking for ways to minimize these crimes, yet the effectiveness of the current reforms can be questioned. In an age where digital data and technology are prevalent, the government would have to find a fair balance between protecting the citizens’ rights and banning illegal content.