The deliverymen behind South Korea’s logistics industry

MR. KANG Chul-chung, a deliveryman under CJ Logistics, begins his day at 6.20 a.m., leaving his house in haste to the logistics warehouse in Yong-san. After hours of unpaid package sorting and distribution in the warehouse, it is only slightly after noon when Kang starts his delivery. With around 400 packages that need to be delivered within the day, Mr. Kang spends another 8 hours delivering packages, just making a commission of approximately 770 per package delivered. The legal limit of 52 working hours per week implemented by the government does not mean anything to Kang who works 70 hours per week. This is the day of an average deliveryman in South Korea; the untold lives of those who bring your packages at your doorsteps.

The prospering industry

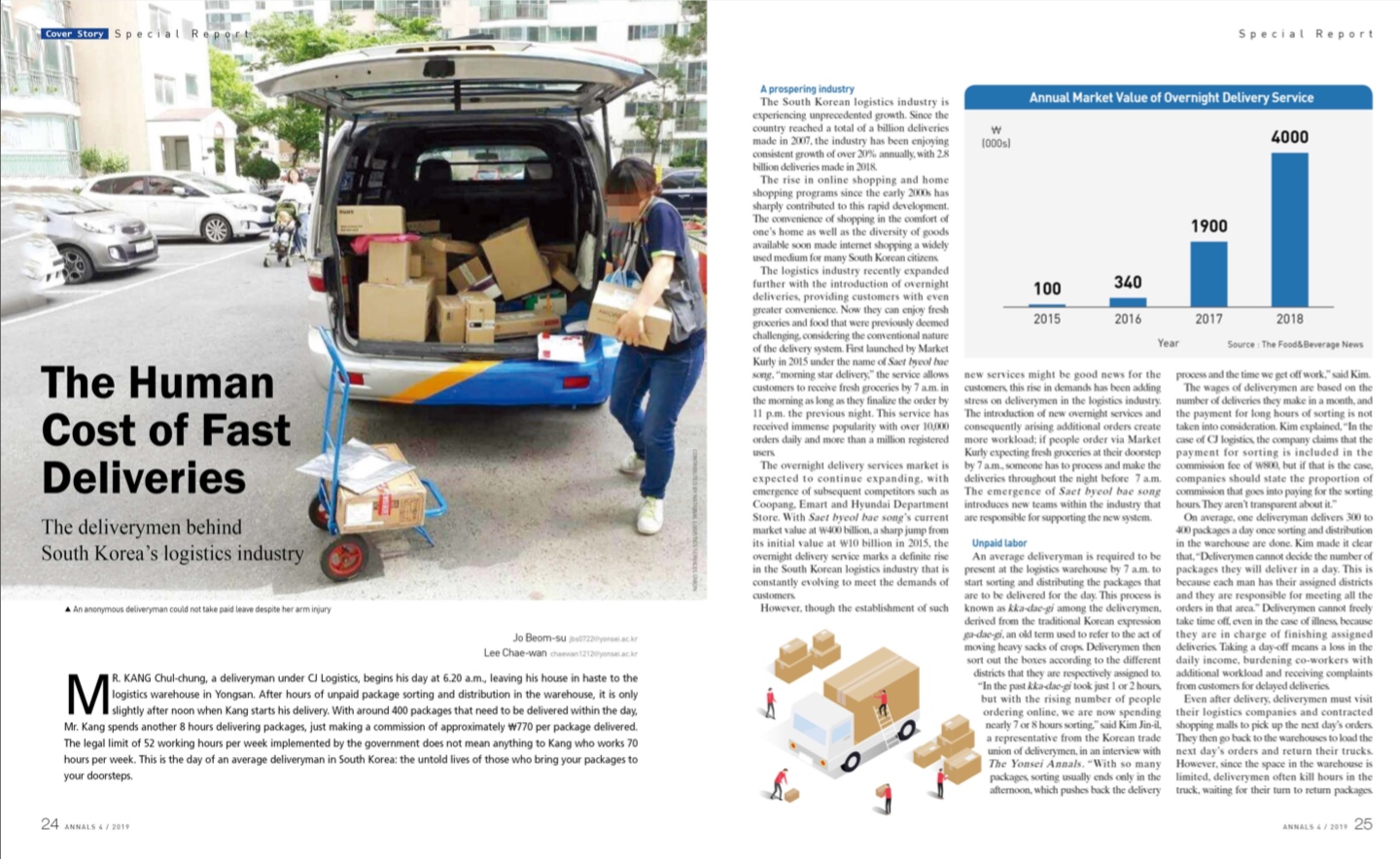

The South Korean logistics industry is experiencing unprecedented growth. Since the country reached a total of a billion deliveries made in 2007, the industry has been enjoying consistent growth of over 20% annually, with 2.8 billion deliveries made in 2018.

The rise in online shopping and home shopping programs since the early 2000s has sharply contributed to this rapid development. The convenience of shopping in the comfort of ones’ homes as well as the diversity of goods available soon made internet shopping a widely used medium for many South Korean citizens.

The logistics industry recently expanded further with the introduction of overnight deliveries, providing the customers with even greater convenience. Now they can enjoy fresh groceries and food that were previously deemed challenging, considering the conventional nature of the delivery system. First launched by Market Kurly in 2015 under the name Saet byeol bae song, “morning star delivery,” the service allows customers to receive fresh groceries by 7 a.m. in the morning as long as they finalize the order by 11 p.m. the previous night. This service has received immense popularity with over 10,000 orders daily and more than a million registered users.

The overnight delivery services market is expected to continue expanding, with emergence of subsequent competitors such as Coopang, Emart and Hyundai Department Store. With Saet byeol bae song’s current market value at 400 billion, a sharp jump from its initial value at ₩10 billion in 2015, the overnight delivery service marks a definite rise in the South Korean logistics industry that is constantly evolving to meet the demands of customers.

However, though the establishment of such new services might be good news for the customers, this rise in demands places has been adding stress on those deliverymen in the logistics industry. The introduction of new overnight services and consequently arising additional orders create more workload; if people order via Market Kurly expecting fresh groceries at their doorstep by 7 a.m., someone has to process and make the deliveries throughout the night before 7 a.m. The emergence of Saet byeol bae song introduces new teams within the industry that are responsible for supporting the new system.

Unpaid labor

An average deliveryman is required to be present at the logistics warehouse by 7 a.m. to start sorting and distributing the packages that are to be delivered for the day. This process is known as kka-dae-gi among the deliverymen, derived from the traditional Korean expression ga-dae-gi, an old term used to refer to the act of moving heavy sacks of crops. Deliverymen then sort out the boxes according to the different districts that they are respectively assigned to. “In the past kka-dae-gi took just one or two hours, but with the rising number of people ordering online, we are now spending nearly seven or eight hours sorting,” said Kim Jin-il, a representative from the Korean trade union of deliverymen, in an interview with The Yonsei Annals. “With so many packages, sorting usually ends only in the afternoon, which pushes back the delivery process and the time we get off work,” said Kim.

The wages of deliverymen are based on the number of deliveries they make in a month, and the payment for long hours of sorting is not taken into consideration. Kim explained, “In the case of CJ logistics, the company claims that the payment for sorting is included in the commission fee of ₩800, but if that is the case, companies should state the proportion of commission that goes into paying for the sorting hours. They aren’t transparent about it.”

On average, one deliveryman delivers 300 to 400 packages a day once sorting and distribution in the warehouse are done. Kim made it clear that, “Deliverymen cannot decide the number of packages they will deliver in a day. This is because each man has their assigned districts and they are responsible for meeting all the orders in that area.” Deliverymen cannot freely take time off, even in the case of illness, because they are in charge of finishing assigned deliveries. Taking a day-off means a loss in the daily income, burdening co-workers with additional workload and complaints from customers for delayed deliveries.

Even after delivery, deliverymen must visit their logistics companies and contracted shopping malls to pick up the next day’s orders. They then go back to the warehouses to load the next day’s orders and return their trucks. However, since the space in the warehouse is limited, deliverymen often kill hours in the truck, waiting for their turn to return packages. Kim emphasized, “Waiting hours after work are also unpaid and taken for granted. They come in at 7 a.m. and finish work at 10 p.m. or even 11 p.m.”

Despite the long working hours, more than half of the time is unpaid by logistics companies. As a result, according to the Korea Transport Institute’s report in 2015, a deliveryman works 14.8 hours a day and a total of 24.9 days a month on average. However, since their work is conveniently counted through commission, the total amount of time spent that contributes to their wage is minimal. Kim mentioned, “Despite the long working hours, it is estimated that we receive just a little more than the minimum wage per hour.” Reports from the Ministry of Environment and Labor in 2015 prove this claim; the actual monthly wage for a deliveryman is only approximately ₩2.27 million.

Safety net unavailable

While the conditions for deliverymen violate Labor and Employment Law, deliverymen are unable to turn to the South Korean justice system for help. A majority of deliverymen are registered as self-employed business owners who do not fall into the category of “laborers” protected under the Labor and Employment Law. In an interview with CBS Radio, Yoo Sung-wook explained, “This system began in 1997, during the Asian Financial Crisis when companies requested their employees to switch their status as self-employed owners to reduce costs of labor and production.” In an interview with the Annals Kim Jin-il commented, “There are three big things that the Labor and Employment Law protects—contractual relationship, wages and annual paid leaves. However, deliverymen are subject to constant threats of losing their contracts with logistics companies, delayed incomes, and a lack of paid leaves.”

Deliverymen cannot enjoy annual paid leaves since such day-offs would incur heavy costs. An anonymous deliveryman wrote a post on the internet café for deliverymen, as he was quitting his work: “While working as a deliveryman for 15 years, I have never been on a proper vacation before. When my father died, I took one week off and it cost me ₩2 million. I sincerely regret living like a machine for the past 15 years and not taking care of my family.”

Another serious threat for deliverymen is that logistics companies can lay them off without prior notice. Fired workers are not protected by the Labor and Employment Law and cannot file a claim for wrongful dismissal; the most they can do is file a civil lawsuit.

In one case, a deliveryman was fired by CJ Logistics Company Busan because he unintentionally failed to return the payment of ₩28,000 from a collect-on-delivery package to the headquarter. He was laid-off on the grounds of embezzlement. In an interview with Hankyoreh he explained, “I often deliver up to 450 packages a day. Work can go on until 11 p.m. and on that day, I worked for 14 hours. Since I was too exhausted, I forgot to submit ₩28,000 to the headquarters but it was not an act of embezzlement. The logistics company did not listen to me at all before laying me off.”

Little welfare for the deliverymen

To avoid further responsibilities regarding labor rights and the welfare of deliverymen, many logistics companies’ headquarters are outsourcing their delivery work. Instead of employing deliverymen directly, logistics companies have been outsourcing to intermediary delivery agencies which in turn sign contracts with deliverymen who are registered as self-employed workers. With the deliverymen registered as self-employed workers contracted to delivery agencies, logistics firms are not mandated to provide deliverymen with even the basic necessities for work—trucks, fuel costs, uniforms and even invoices. In the case of an emergency, for instance if a deliveryman were to get seriously injured, logistic headquarters are not liable and instead delivery agencies carry on that role.

Given the physical work entailed in the job, health insurance is a priority that needs to be taken care of by the employers. Surveys from Korea Labor Institute show that 40.1% of deliverymen have experienced at least one car accident per year; 66.8% suffer from bad cramps and 58.6% are experiencing fatigue. However, only 10% of the deliverymen are protected by health and safety insurance; the other 90% are exposed to insecurity. The reason that most deliverymen cannot sign up for health and safety insurance is that delivery agencies prevent such acts, threatening to end their contracts. According to SBS’s footage in April 2017, the contract for a deliveryman with Coopang ended abruptly because he took a leave of absence under the health and safety insurance.

Despite poor working conditions, many deliverymen still renew their contracts because, “We need to earn money,” said Kim Jin-il in an interview with the Annals. When asked if he had known about the poor working environments and the unfair terms of contracts, Kim answered yes.

Hope for the future?

Kim suggests two ways to improve the working conditions of deliverymen. One cause of long working hours is a low commission fee. If this commission fee increases, deliverymen can work less hours and still earn enough income to afford their lives. After deducting tax, a deliveryman would often receive less than ₩770 for one package. However, a second more feasible and fundamental solution Kim suggests is to devise a system that minimizes the sorting and distribution process, allowing deliverymen to start the delivery process early. This means they can go home much earlier at around 6 to 7 p.m. and spend less time doing unpaid work.

However, apart from these recommendations to modify the work structure, deliverymen still remain outside of conventional worker protection. Aside from the lack of applicability of labor laws, deliverymen also cannot apply for Industrial Compensation Insurance, insurance almost automatically provided to all workers in warehouses and factories. The government has shown effort to patch up these loopholes. Most notably, the government has implemented a number of policies regarding Persons in Special Type of Employment—a term formulated to refer to employees who are not protected by conventional labor laws. The occupations that fall under this category are determined through presidential decree, and deliverymen fall within this category, along with other occupations such as golf caddies and insurance planners.

Some of the government initiatives for these Persons in Special Type of Employment include allowing exceptional openings for registration of Industrial Compensation Insurance from July 2008, acknowledging the high likelihood of occupational hazards and the need for legal protection of those unconventional workers. Deliverymen now have the option to apply for an insurance claim when they encounter incidents during their work.

Additionally, with President Moon Jae-in’s urge to strengthen the legal protection of Persons in Special Type of Employment, there is a positive speculation that the labor condition and rights for the deliveryman would improve even further. “As there are several differing occupations under the category of Persons in Special Type of Employment, we have to strategically categorize and resolve the issue instead of collectively enforcing the legal protection,” stated Moon in a joint lunch with Prime Minister Lee Nak-yeon on 2nd July, 2018.

With the call for labor rights in occupations that were once neglected, further government measures pertaining to the rights of deliverymen are projected to be implemented gradually over time. Some fundamental reforms include the application of “three rights of laborer” under article 33 of the constitution—the right to independent association, collective bargaining and collective action to the occupations of Persons in Special Type of Employment such as the deliverymen.

* * *

As logistics companies expand to accommodate the demand for convenience in the 21st century, tension is put on operational services. Though the logistics industry is experiencing rapid advancement, the employment structure of the delivery industry has remained unchanged; the structure that was established during the time of crisis still continues to impose insecurity upon the fundamental manpower that is sustaining the industry. Time has changed and alterations should be made to the structure as well. Before we celebrate the rapid success of Korean logistics industry there is a need to reflect if our system is exemplary in the first place.

*Industrial Compensation Insurance: One of the four mandatory insurances that employees are entitled to join when granted employment; it provides relevant compensations for work-related accidents as well as financial support for rehabilitation of the injured workers so they can return to work.

Jo Beom-su, Lee Chae-wan

jbs0722@yonsei.ac.kr, chaewan1212@yonsei.ac.kr