The 2019 Japan boycott’s economic and societal implications

“JAPAN MAY condescend to Korea regarding our complicated history, but it doesn’t help if Korea undiscriminatingly labels people who aren’t outright anti-Japan as national traitors,” said An Sung-min (Fresh., Dept. of Mechanical Engineering, Waseda Univ.). A Korean student currently studying in Japan, An senses the sentiments of both nations going to the extreme, especially with the ongoing economic sanctions and boycott movements. Japanese brands in Korea are drastically losing businesses, and Japanese corporations even resorted to reducing a significant number of regional branches in the country. Amidst gradual exacerbation of tension, the two nations are reciprocally experiencing both economic and social ripple effects that are shaking both societies. With deeply embedded hatred between the two at a critical point, the outcome of the conflict remains elusive.

Lighting the fuse

The recent nation-wide Japan boycott movement ignited in Korea when Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe publicly announced the implementation of economic sanctions against Korea. At an official press conference on July 1, 2019, the Japanese Ministry of Economy and Industrial Affairs enforced limits on the export of a number of essential factors of production for semiconductors and display devices, explicitly expressing its intentions to place sanctions on the Korean economy. Such sanctions were speculated to be a retaliatory measure against the Republic of Korea Supreme Court’s ruling on October 30, 2018 pertaining to compensations for Japan’s wartime crimes. The Court decreed that Japanese corporation Nippon Steel should compensate for their forced labor drafting during the war, enforcing sequestration of the company’s assets. The following verdict was especially controversial as it overruled the 1965 Korea-Japan agreement, a treaty signed by the Republic of Korea and Japan on June 22, 1965 to reciprocally define their diplomatic relations. Apart from the restriction on certain industrial exports, the Japanese government also removed Korea from its “White List” of trade partners, indicating that South Korea’s previous privileged status which granted preferential economic treatments would also be eliminated. Such decisions are indeed regretful, with Japan contradicting several of its pledges made recently most notably the country’s stress on “free and equal trade” at the 2019 G20 Osaka Summit.

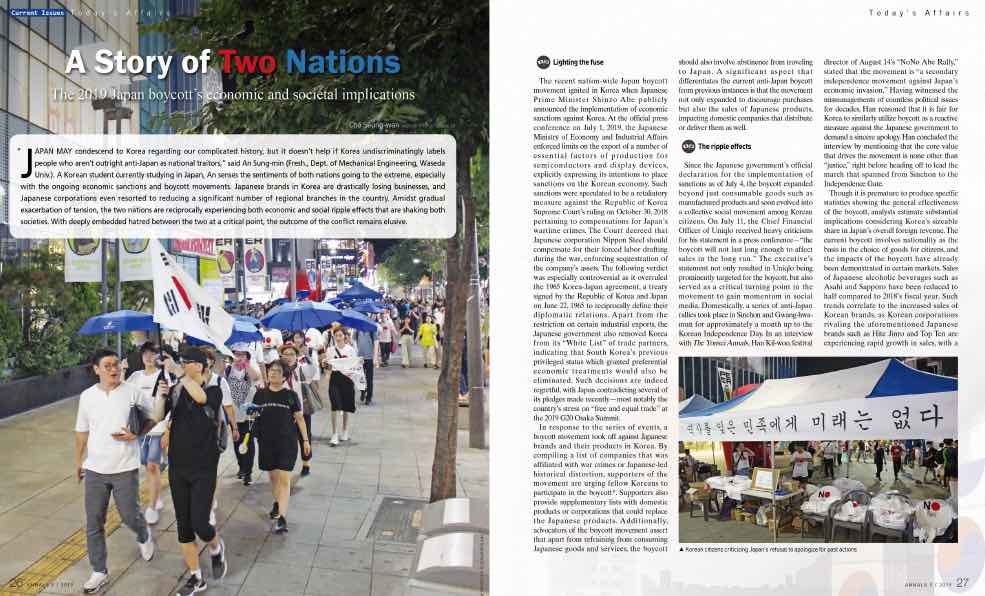

In response to the series of events, a boycott movement took off against Japanese brands and their products in Korea. By compiling a list of companies that was affiliated with war crimes or Japanese-led historical distortion, supporters of the movement are urging fellow Koreans to participate in the boycott*. Supporters also provide supplementarylists with domestic products or corporations that could replace the Japanese products. Additionally, advocators of the boycott movement assert that apart from refraining from consuming Japanese goods and services, the boycott should also involve abstinence from traveling to Japan. A significant aspect that differentiates the current anti-Japan boycott from previous instances is that the movement not only expanded to discourage purchases but also the sales of Japanese products, impacting domestic companies that distribute or deliver them as well.

The ripple effects

Since the Japanese government’s official declaration for the implementation of sanctions as of July 4, the boycott expanded beyond just consumable goods such as manufactured products and soon evolved into collective social movements among Korean citizens. On July 11, the Chief Financial Officer of Uniqlo received heavy criticisms for his statement in a press conference—“the boycott will not last long enough to affect sales in the long run.” The executive’s statement not only resulted in Uniqlo being prominently targeted for the boycott, but also served as a critical turning point in the movement to gain momentum in social media. Domestically, a series of anti-Japan rallies took place in Sinchon and Gwang-hwa-mun for approximately a month up to the Korean Independence Day. In an interview with The Yonsei Annals, Han Kil-woo, festival director of August 14’s “NoNo Abe Rally,” stated that the movement is “a secondary independence movement against Japan’s economic invasion.” Having witnessed the mismanagements of countless political issues for decades, Han reasoned that it is fair for Korea to similarly utilize boycott as reactive measures against the Japanese government to demand a sincere apology. Han concluded the interview by mentioning that the core value that drives the movement is none other than “justice,” right before heading off to lead the march that spanned from Sinchon to the Independence Gate.

Though it is premature to produce specific statistics showing the general effectiveness of the boycott, analysts estimate substantial implications considering Korea’s sizeable share in Japan’s overall foreign revenue. The current boycott involves nationality as the basis in the choice of goods for citizens, and the impacts of the boycott have already been demonstrated in certain markets. Sales of Japanese alcoholic beverages such as Asahi and Sapporo have been reduced to half compared to 2018’s fiscal year. Such trends correlated to the increased sales of Korean brands, as Korean corporations rivaling the aforementioned Japanese brands such as Hite Jinro and Top Ten are experiencing rapid growth in sales, with a 220% increase compared to the prior week in mid-July. Noticeable effects of the boycott can also be observed within the stock market, as several Japan-related tourist companies displayed trends of stagnation while stocks of their South Korean rivals have skyrocketed**.

The boycott movement also influenced the political interaction between the two countries. According to polls conducted by Gallup Korea as of July, 67% of Korean respondents expressed support for the anti-Japan boycott movement, and a considerable 80% additionally expressed intentions to discourage the purchase of Japanese products to others. The sentiment of hostility is also similar in Japan, as right-wing domestic journalists are publicly criticizing Korea’s boycott, belittling that the movement would be “ineffective since Korea is a small nation.” Japanese citizens are also attempting to discourage the sale and purchase of Korean products, effectively instigating a boycott resembling that of Koreans.

The pedigree

The recent movement is not the first instance of Korea’s boycott movement against Japan. Dating back as far as the 1920s during the era of Japanese colonialism, the Mul-san Jang-ryeo*** movement was a pivotal part of Korean citizens’ efforts towards independence. Despite the stark difference in timeline, the movements share many characteristics in that they both utilize curtailing consumptions of foreign goods and services as a mode of political retribution as well as facilitation of domestic economic growth. Even after the independence, President Park Chung-hee’s era carried out subsequent boycotts, triggered by the Korea-Japan Agreement in 1965 and Japanese corporations’ discrimination of Koreans in employment****. The boycott movements continued into the 1990s and the early 2000s, with conflicted views towards the comfort women issue and the Japanese government’s territorial claims of Dokdo Island propelling anti-Japan sentiments.

The current tensions in Korea and Japan’s economic and social relationship originated from a tenuous history, as the two nations identify each other as “a close but distant country.” With the majority of negative sentiments towards Japan affiliated with inadequate resolution of past history, the progression of diplomacy has revolved around the goals of justice and reconciliation. Following the Japanese occupation of Korea from the 1910s to 1945, Japan’s refusal to apologize for past affronts, such as the drafting Korean women as wartime sexual slaves or citizens as involuntary laborers and soldiers, have led to significant accumulation of anti-Japanese sentiments. Despite the numerous cultural exchanges and the current relationship between the two nations as political allies, the accumulation of resentment and rivalry still remains a deep-seated factor in the Korea-Japan relationship.

Where do we go from here?

Following Japanese Prime Minister Abe’s announcement, Minister of Foreign Affairs Kang Kyung-hwa expressed a resolute standpoint against Korea’s exclusion from Japan’s White List. According to Minister Kang, under the condition that the sanctions continue, the Korean government would also have to introduce retaliatory policies in response, reflecting the public sentiment of the majority of Korean citizens on the issue. Though Minister Kang stated that the two nations will proceed with negotiations to resolve the potential threat to the economies of both nations, the likelihood of resolution seems bleak from the latest summit with Japanese Minister of Diplomacy Gono Daro in July 1, 2019, failing to reach an agreement regarding the finalization of Japan’s White List exclusion of South Korea*****. Even a joint summit with the U.S. representative—the intervention of a third party—a day after the initial summit, did not yield significant results. Ultimately, the Korean government announced on August 12 that Japan will also be excluded from its own White List, continuing the line of retaliatory policies.

Analyzing the recent Korea-Japan conflicts, Jho Hwa-sun (Prof., Dept. of Political Science & Int. Studies) stated that the current situation should be regarded “in the context of collective changes in international relations.” Following the fall of traditional liberal international relations and the instigation of rivalry between hegemonic states, how Korea would resolve its conflicts with Japan should be a determinant of international peace and prosperity. In an interview with the Annals, Professor Kim Jung (Prof., Dept. of Political Science, University of North Korean Studies) also provided his insight into the issue, highlighting the factor of diplomatic vagueness as the key defining feature of Korea-Japan relations. The ambiguity in 1965’s agreement clauses might have granted reciprocal satisfaction at the time, but it ultimately led to exacerbate the buildup of political disputes and negative sentiments over the decades. Considering the system of representative democracy, Kim stated that it is “only natural that the governments of both nations are rallying their citizens’ support.”

Additionally, Kim also identified numerous rifts between the two nations as detrimental factors. As Kim mentions, the initial decision of the Korean Supreme Court, or the Korean Department of Justice, contradicts with the prior agreement the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had made with the Japanese government over five decades ago—the recent ruling of the Court was based upon a progressive interpretation of legislation based on human rights. It was also not a decision that reflected the administrative government’s need for a congenial diplomatic relationship with Japan. Such phenomenon is also present in the Japanese government, as their Ministry of Diplomacy and administrative government is displaying contradictory views. The fissure between citizens and the government is also certainly present as their political demands differ. While citizens demand societal justice for Japan’s past actions against the nation, the government’s interests are intimately linked to reconciliation necessary for sustaining the long-term diplomatic relations.

Since Korea and Japan are currently performing social action primarily geared towards retaliation, how the boycott movement and recent Korea-Japan conflicts will reach an ending is quite unclear. Korea greatly emphasizes the values of justice and compensation for past atrocities, while Japan refuses to renounce its own interpretation of past agreements. “In order for Korea and Japan to reach a significant agreement, re-introducing diplomatic ambiguity could be the key to the reconciliation between the two nations,” stated Professor Kim, who believes that rendering the current international conflict into a freeze state would be the shortcut to mutual satisfaction.

* * *

The economic sanctions and boycott movements of both nations possess a simple logic: to fight fire with fire. It is certainly true that the origins of the conflict date back more than a century, with numerous factors such as political and societal rifts being forces to be reckoned with. Despite both nations believing there is justification in their own decisions so far, the most effective solution to the current dispute seems not to be in concession or compromise, but in reaching the discussion table. While it is ineffective to seek unconditional reconciliation between Korea and Japan, refusing to heed each others’ standpoints and continuing the long chain of dispute is more than an undesirable future for the two nations.

*Nono Japan

**Naver News

***Mul-san Jang-ryeo: Korea’s pan-national economic independence movement during the Japanese occupation in the 1920s

****Seoul Newspaper

*****MSN News

Cho Seung-wan

wanwin99@yonsei.ac.kr