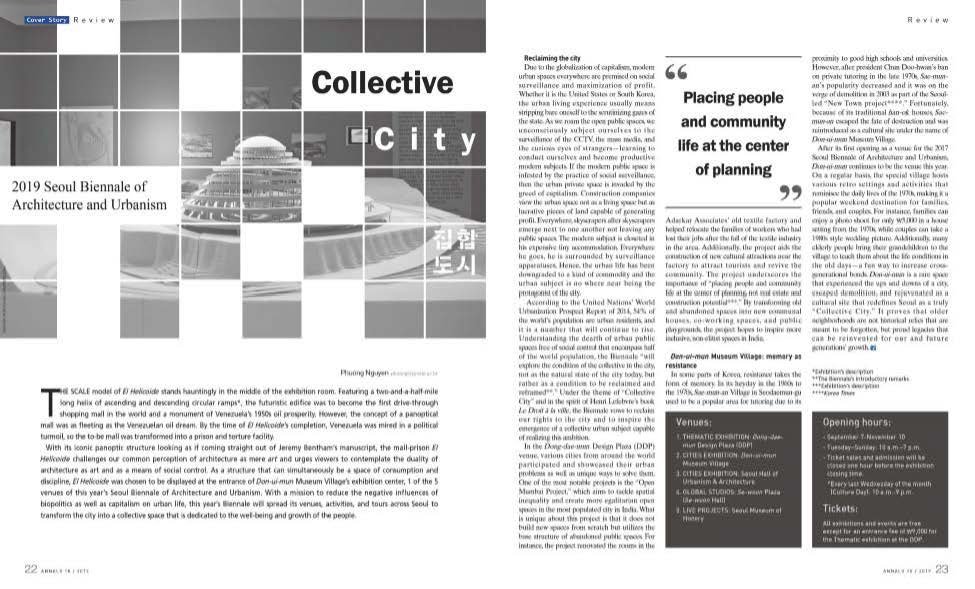

2019 Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism

THE SCALE model of El Helicoide stands hauntingly in the middle of the exhibition room. Featuring a two-and-a-half-mile long helix of ascending and descending circular ramps*, the futuristic edifice was to become the first drive-through shopping mall in the world and a monument of Venezuela’s 1950s oil prosperity. However, the concept of a panoptical mall was as fleeting as the Venezuelan oil dream. By the time of El Helicoide’s completion, Venezuela was mired in a political turmoil, so the to-be mall was transformed into a prison and torture facility.

With its iconic panoptic structure looking as if coming straight out of Jeremy Bentham’s manuscript, the mall-prison El Helicoide challenges our common perception of architecture as mere art and urges viewers to contemplate the duality of architecture as art and as a means of social control. As a structure that can simultaneously be a space of consumption and discipline, El Helicoide was chosen to be displayed at the entrance of Don-ui-mun Museum Village’s exhibition center, 1 of the 5 venues of this year’s Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism. With a mission to reduce the negative influences of biopolitics as well as capitalism on urban life, this year’s Biennale will spread its venues, activities, and tours across Seoul to transform the city into a collective space that is dedicated for the well-being and growth of the people.

Reclaiming the city

Due to the globalization of capitalism, modern urban spaces everywhere are premised on social surveillance and maximization of profit. Whether it is the United States or South Korea, the urban living experience usually means stripping bare oneself to the scrutinizing gazes of the state. As we roam the open public spaces, we unconsciously subject ourselves to the surveillance of the CCTV, the mass media, and the curious eyes of strangers—learning to conduct ourselves and become productive modern subjects. If the modern public space is infested by the practice of social surveillance, then the urban private space is invaded by the greed of capitalism. Construction companies view the urban space not as a living space but as lucrative pieces of land capable of generating profit. Everywhere, skyscrapers after skyscrapers emerge next to one another without any public spaces. The modern subject is closeted in his expensive tiny accommodation. Everywhere he goes, he is surrounded by surveillance apparatuses. Hence, the urban life has been downgraded to a kind of commodity and the urban subject no where near being the protagonist of the city.

According to the United Nations’ World Urbanization Prospect Report of 2014, 54% of the world’s population are urban residents, and it is a number that will continue to rise. Understanding the dearth of urban public spaces free of social control that encompasses half of the world population, the Biennale “will explore the condition of the collective in the city, not as the natural state of the city today, but rather as a condition to be reclaimed and reframed**.” Under the theme of “Collective City” and in the spirit of Henri Lefebvre’s book Le Droit à la ville, the Biennale vows to reclaim our rights to the city and to inspire the emergence of a collective urban subject capable of realizing this ambition.

In the Dong-dae-mun Design Plaza (DDP) venue, various cities from around the world participated and showcased their urban problems as well as unique ways to solve them. One of the most notable projects is the “Open Mumbai Project,” which aims to tackle spatial inequality and creates more egalitarian open spaces in the most populated city in India. What is unique about this project is that it does not build new spaces from scratch but utilizes the base structure of abandoned public spaces. For instance, the project renovated the rooms in the Adarkar Associates’ old textile factory and helped relocate the families of workers who had lost their jobs after the fall of the textile industry in the area. Additionally, the project also aids the construction of new cultural attractions near the factory to attract tourists and revive the community. The project underscores the importance of “placing people and community life at the center of planning, not real estate and construction potential***.” By transforming old and abandoned spaces into new communal houses, co-working spaces and public playgrounds, the project hopes to inspire more inclusive, non-elitist spaces in India.

Don-ui-mun Museum Village: memory as resistance

In some parts of Korea, resistance takes the form of memory. In its heyday in the 1960s to the 1970s, Sae-mun-an Village in Seodaemun-gu used to be a popular area for tutoring due to its proximity to good high schools and universities. However, after president Chun Doo-hwan’s ban on private tutoring in the late 1970s, Sae-mun-an’s popularity decreased and it was on the verge of demolition in 2003 as part of the Seoul-led “New Town project****.” Fortunately, because of its traditional han-ok houses, Sae-mun-an escaped the fate of destruction and was reintroduced as a cultural site under the name of Don-ui-mun Museum Village.

After its first opening as a venue for the 2017 Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, Don-ui-mun continues to be the venue for this year. On a regular basis, the special village hosts various retro settings and activities that reminisce the daily lives of the 1970s, making it a popular weekend destination for families, friends, and couples. For instance, families can enjoy a photo shoot for only ₩5,000 in a house setting from the 1970s while couples can take a 1980s style wedding picture. Additionally, many elderly people bring their grandchildren to the village to teach them about the life conditions in the old days, a fun way to increase cross-generational bonds. Don-ui-mun is a rare space that experienced the ups and downs of a city, escaped demolition, and rejuvenated as a cultural site that redefines Seoul as a truly “Collective City.” It proves that older neighborhoods are not historical relics that are meant to be forgotten but proud legacies that can be reinvented for our and future generations’ growth.

Venues:

1. THEMATIC EXHIBITION: Dong-dae-mun Design Plaza (DDP)

2. CITIES EXHIBITION: Don-ui-mun Museum Village

3. CITIES EXHIBITION: Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Architecture

4. GLOBAL STUDIOS: Se-woon Plaza (Se-woon Hall)

5. LIVE PROJECTS: Seoul Museum of History

Opening hours:

Tuesday–Sunday: 10 a.m.–7 p.m.

Ticket sales and admission will be closed one hour before the exhibition closing time.

※ Every last Wednesday of the month (Culture Day): 10 a.m.-9 p.m.

Tickets:

All exhibitions and events are free except for an entrance fee of ₩9,000 for the Thematic exhibition at the DDP.

*Exhibition’s description

**The Biennale’s introduction remark

***Exhibition’s description

****Korea Times

Nguyen Thi Lan Phuong

phuong@yonsei.ac.kr