| | | |

LEE YOUNG-EUN is an ordinary Korean citizen. She was born in Korea, received Korean public education from elementary to high school, and is now attending university in Seoul. Lee’s mother tongue is Korean, and like many of her peers, she identifies tteok-bo-kki as her comfort food. During her free time, Lee binge watches Korean TV shows and listens to her favorite group, EXO. From how she describes herself, Lee seems like a typical Korean college student. However, Lee has never felt that Korean society had accepted her for who she is—a Korean. Her slightly tanned skin and larger facial features from her Filipino mother’s side often have people questioning how “authentically” Korean she is. Lee, along with many others burdened with the “multicultural family” label, struggle every day to fit into a society they should naturally be a part of—the Korean society.

“We are not second-class citizens”

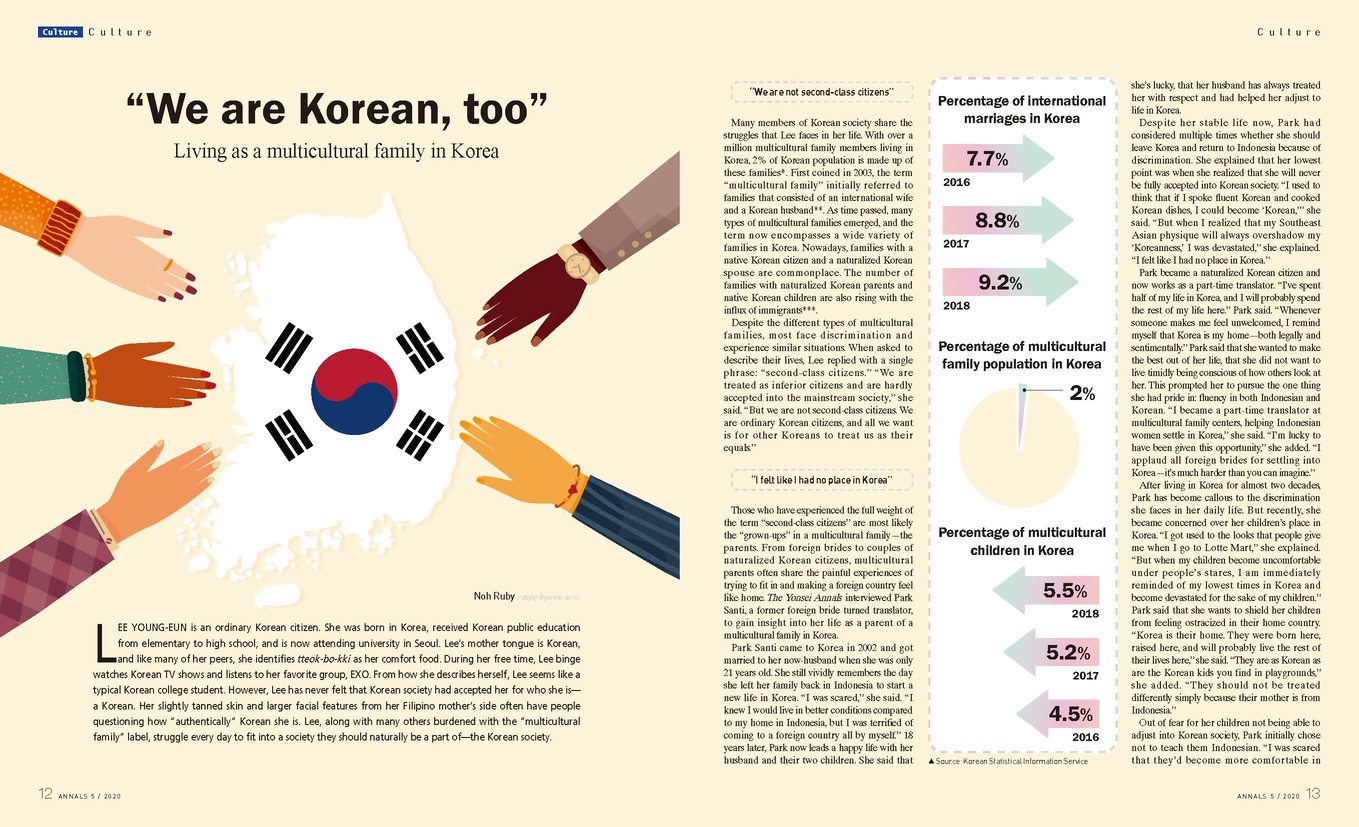

Many members of Korean society share the struggles that Lee faces in her life. With over a million multicultural family members living in Korea, 2% of Korean population is made up of these families*. First coined in 2003, the term “multicultural family” initially referred to families that consisted of an international wife and a Korean husband**. As time passed, many types of multicultural families emerged, and the term now encompasses a wide variety of families in Korea. Nowadays, families with a native Korean citizen and a naturalized Korean spouse are commonplace. The number of families with naturalized Korean parents and native Korean children are also rising with the influx of immigrants***.

Despite the different types of multicultural families, most face discrimination and experience similar situations. When asked to describe their lives, Lee replied with a single phrase: “second-class citizens.” “We are treated as inferior citizens and are hardly accepted into the mainstream society,” she said. “But we are not second-class citizens,” she explained. “We are ordinary Korean citizens, and all we want is for other Koreans to treat us as their equals.”

“I felt like I had no place in Korea”

Those who have experienced the full weight of the term “second-class citizens” are most likely the “grown-ups” in a multicultural family—the parents. From foreign brides to couples of naturalized Korean citizens, multicultural parents often share the painful experiences of trying to fit in and making a foreign country feel like home. The Yonsei Annals interviewed Park Santi, a former foreign bride turned translator, to gain insight into her life as a parent of a multicultural family in Korea.

Park Santi came to Korea in 2002 and got married to her now-husband when she was only 21 years old. She still vividly remembers the day she left her family back in Indonesia to start a new life in Korea. “I was scared,” she said. “I knew I would live in better conditions compared to my home in Indonesia, but I was terrified of coming to a foreign country all by myself.” 18 years later, Park now leads a happy life with her husband and their two children. She said that she’s lucky, that her husband has always treated her with respect and had helped her adjust to life in Korea.

Despite her stable life now, Park had considered multiple times whether she should leave Korea and return to Indonesia because of discrimination. She explained that her lowest point was when she realized that she will never be fully accepted into Korean society. “I used to think that if I spoke fluent Korean and cooked Korean dishes, I could become ‘Korean,’” she said. “But when I realized that my Southeast Asian physical features will always overshadow my ‘Koreanness,’ I was devastated,” she explained. “I felt like I had no place in Korea.”

Park became a naturalized Korean citizen and now works as a part-time translator. “I’ve spent half of my life in Korea, and I will probably spend the rest of my life here.” Park said. “Whenever someone makes me feel unwelcomed, I remind myself that Korea is my home—both legally and sentimentally.” Park said that she wanted to make the best out of her life, that she did not want to live timidly being conscious of how others look at her. This prompted her to pursue the one thing she had pride in: fluency in both Indonesian and Korean. “I became a part-time translator at multicultural family centers, helping Indonesian women settle in Korea,” she said. “I’m lucky to have been given this opportunity,” she added. “I applaud all foreign brides for settling into Korea—it’s much harder than you can imagine.”

After living in Korea for two decades, Park has become callous to the discrimination she faces in her daily life. But recently, she became concerned over her children’s place in Korea. “I got used to the looks that people give me when I go to Lotte Mart,” she explained. “But when my children become uncomfortable under people’s stares, I am immediately reminded of my lowest times in Korea and become devastated for the sake of my children.” Park said that she wants to shield her children from feeling ostracized in their home country. “Korea is their home. They were born here, raised here, and will probably live the rest of their lives here,” she said. “They are as Korean as are the Korean kids you find in playgrounds,” she added. “They should not be treated differently simply because their mother is from Indonesia.”

Out of fear for her children not being able to adjust into Korean society, Park initially chose not to teach them Indonesian. “I was scared that they’d become more comfortable in Indonesian,” she explained. “I intentionally sent my children to public schools because I wanted them to feel that they belonged in Korean society.” Park said that she dreaded waiting for her children to return from school. “I feared that one day they would come home crying and ask me why they looked ‘different’ and why their friends weren’t letting them play together.” Thankfully, nothing of the sort happened—but Park is still afraid of what she would have to do if her children start to become conscious of their differences compared to their friends.

“I am now teaching my children Indonesian—the other half of their heritage,” she said. “I don’t want to be afraid to teach my kids about Indonesia,” she explained. “They are as Indonesian as they are Korean.” However, as a mother who doesn’t want her children to be hurt, Park is still unsure how to convey the “multiculturalism” within the family. “I think this is a struggle that all multicultural parents face,” she said. “The balance between being Korean and being multicultural is hard to weigh.”

Towards the end of the interview, Park said that our society will only be fully integrated when both native Koreans and multicultural families are ready to embrace one another. “Despite the efforts made by public and civil organizations, most of the policies and aids focus only on multicultural families adjusting into Korean society,” she said. “But it’s not just the multicultural families that need to adapt to a new environment,” she explained. “Native Koreans also need to make an effort to adjust into our increasingly diverse society.” “It’s a two-way street,” she added. “I hope that one day I won’t be hesitant to teach my children Indonesian. I also hope I get to teach native Korean kids Indonesian—those eager to learn about other cultures in Korea.”

“I didn’t feel like I belonged anywhere”

Unlike their parents, most multicultural children are born and raised in Korea. Although they are not much different from non-multicultural Korean children, these children face discrimination and struggle to feel accepted in Korean society. The Annals was able to listen to Lal’s story of growing up as a multicultural child in Korea.

Lal is a native Korean born into a family of first-generation immigrant parents from Pakistan. His parents moved to Korea in 1994 and, four years later, they gave birth to Lal in Korea. He has spent his whole life in Korea, having never stepped foot outside the country. “For 21 years, all I’ve known is Korean culture and a little bit of Pakistani culture I’ve recently begun to learn,” he said.

“My parents knew that they didn’t have the financial resources to send me to an international school,” he recalled. “So as soon as I was able to speak, they taught me Korean.” Growing up, Lal listened to Korean nursery rhymes, read Korean children’s books, and watched Korean TV shows—just like other Korean kids. Lal said that his parents’ strategy of showering him with Korean culture worked. “I was Korean—maybe even more Korean than my friends with native Korean parents,” he said. “Because my parents had me read so many Korean books, I was better at Korean than my ‘real’ Korean friends.”

Lal never realized that he was “different” until he was in fifth grade. “I still remember that day,” said Lal. “It had never occurred to me that I was ‘different,’ that I wasn’t like my friends.” “I was on my way home when someone told me that I was too ‘dark’ to be a real Korean,” he recalled. Upon hearing that remark, Lal slowly started to notice that his family was a little unlike his friends’ families. “When I realized that my parents didn’t look like other Koreans, and that we didn’t have grandparents in Korea to celebrate chu-seok and seol-lal with, things started to click,” Lal explained. “Ever since that day, I’ve lived with a feeling of misplacement.”

During his time in public middle and high schools, Lal faced more discrimination and experienced bullying due to his multicultural background. “From ba-ki-stan**** to jab-jong*****, I’ve been called all kinds of derogatory terms one could name,” he said. “People often told me to go back to my ‘home’ country and to stop exploiting their tax money.” Lal had explained over and over again that his parents were naturalized, and that Korea is his home country, but the bullying never stopped. During his adolescent years, Lal considered moving to Pakistan, in hopes of being accepted as one of their own. However, Lal soon realized that on top of not knowing the language, he didn’t know anything about Pakistani culture apart from the occasional Pakistani dishes his mother made. “High school is a period of my life that I never want to go through again,” he recalled. “I genuinely understood what it meant to be lost—I didn’t feel like I belonged anywhere.”

Lal had hoped to form his identity when he went to college. Instead, he felt even more lost. “I reached out to both native Koreans and foreign students, but I felt left out in both groups,” he explained. Lal’s distinct physical features set him apart from native Koreans, and him being able to only speak Korean made it hard to get along with foreign students. “I felt like the native Koreans’ antagonism towards me got worse in college,” he said. Lal remembered being blamed for the rising competitiveness in college examinations and job recruitments, as some native Korean students claimed the “real” Koreans are being robbed of opportunities while “free passes” are given to multicultural children. “I did indeed benefit from the multicultural family policies in pursuing higher education,” he said. “But I also felt that multicultural children have become a scapegoat for the injustices in Korea.”

Upon graduating college, Lal is planning to join the military next year. “I don’t know whether I’m going to give up my Pakistani nationality,” he said. “With all of my family in Korea, I would never settle down in Pakistan, but it’d be good to have a second choice to fall back on.” When asked whether he had fully formed his identity, Lal replied “no.” “I am coming to terms with being a multicultural Korean citizen,” he explained. “I may never fit in anywhere.” Lal claimed that not all multicultural children struggle with their identities. His siblings, for example, have accepted their multicultural background and are satisfied in that they get to enjoy both Korean and Pakistani heritage. “But for me, I am still lost,” Lal explained. “I’m lost with my identity and my future path, and I hope I sort things out soon.”

“Oneness can be achieved through diversity”

Multicultural families have now become integral members of Korean society. With the rising number of foreigners coming into Korea and the increasing rate of international marriages, multicultural families will make up a significant portion of Korean population in the years to come. Despite their growing numbers, multicultural families are still victims of discrimination, facing strict barriers and feeling ostracized in the country they call home.

Throughout the interviews, many interviewees explained that the “multicultural family” label heightens the sense of separation between them and “real” Koreans. They felt that the concept of “multicultural family” and being a Korean has become mutually exclusive. “In essence, if you identify yourself as a member of a ‘multicultural family,’ people will not treat you as a ‘Korean’ anymore,” Lee explained. In order for multicultural families to be fully integrated and not feel like second-rank citizens, Korean society needs to accept that an individual can be both Korean and a multicultural family member at the same time. Belief in monoculturalism and racial homogeneity are deeply rooted in Korean culture. Experts refer to Korea’s dan il min jok****** history as a decisive factor that makes it harder to combine multiculturalism into Korea’s national identity. Over the years, these long held beliefs shaped Korea to strive for unitedness and oneness among themselves. However, with Korean society becoming increasingly diverse and international, Korea needs to accept multiculturalism and diversity into their national values*******. Ultimately, Korea needs to realize that oneness can be achieved through diversity.

Up until now, Korea has mainly focused on getting multicultural families to adjust into Korean culture. However, getting Korean society acquainted with these various cultures is just as important in order to establish an accepting and harmonious society********. Oneness cannot be attained with only one of the stakeholders trying—both Korean society and the multicultural families need to work together to fully understand each other. Only then will Park not be afraid to introduce her children to their Indonesian heritage; only then will Lee and Lal feel wholly accepted by Korean society; only then will oneness through diversity be achieved.

*Korean Statistical Information Service

**Maeil Business Newspaper

***The Asan institute for Foreign Studies

****ba-ki-stan: Derogatory Korean term for Pakistani multicultural families

*****jab-jong: Derogatory Korean term for bi-racial and multicultural children

******dan il min jok: Korean term for a racially homogeneous nation

*******The Asan institute for Foreign Studies

********Yonhap News Agency