Bang-a, a scientific treasure

"KOONG DUCK koong duck!" A rhythmic tone echoes through the air as the Didil Bang-a (Foot operated mill) pounds crops. With this sound, three people singing songs together, work to finish their chores before the sun sets. Two people step on the foothold while the other person mixes the rice at the other end. This was a common scene up until the end of the Chosun Dynasty.

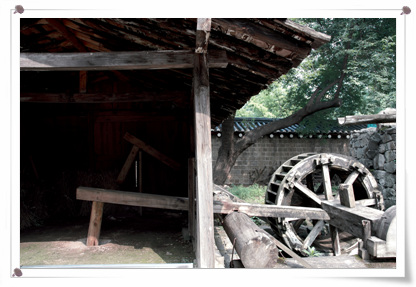

▲ Mulle Bang-a, operated with water

Bang-a, a traditional Korean farming implement, is used to pound or powder dried crops. The beginning of its use goes way back to the New Stone Age. "From the grinding stone, two different tools were derived, the bang-a and the millstone. As farming techniques developed, other tools followed, and today there are many kinds of bang-as all over the country," says Jung Yon-hak, a curator of The National Folk Museum of Korea. The exact time when the bang-a appeared in Korean history is not clear. However, as bang-as were quite familiar to Koreans, they were used as the subject of songs, idioms, plays, and novels.

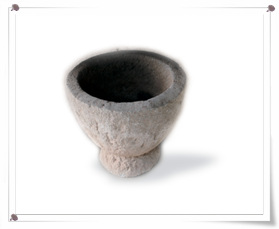

There are various kinds of bang-as in Korea. They can be divided into three categories depending on their source of power. First Jeolgu is operated with hands, and Didil Bang-a is worked by feet. Lastly Mulle Bang-a and Tong Bang-a are operated with water. The basic concept of a bang-a is to pound the crops with the pounder inside the mortar. Experts today consider this process to have been technologically advanced for its time.

As a tool used from the beginning of our cultivation culture, the bang-a has become culturally symbolic. "Since a bang-a was difficult to make, it symbolized the wealth of the family at the time. Every bang-a had the date of its production and the name of the maker carved in its body and people took utmost care of them," says Jung. Bang-a also implies the cooperative Korean farming society. Because there was only one bang-a in a village, the villagers had to take turns using it. When people were waiting in line for their turn, they would help the group ahead of them to finish up the work quickly.

▲ Jeolgu, operated with hands

Since the bang-a has been used for a long time in Korean agricultural society, many superstitions about it have been passed down. People thought that the powerful pounding look of mulle bang-a resembled sexual action between man and woman. So it was believed that if people had sex behind it they would succeed in producing a baby boy. Also didil bang-a was used in a ritual praying for rain. People thought that it looked like a woman lying down with legs spread apart. So people came to believe that if the sky (symbolizing man) saw inside the didil bang-a covered in cloth (which symbolizes woman) it would give them rain. This theory made women go to other villages, steal bang-a and stick them up in the air in hopes for rain.

Today, traditional bang-as aren't used as much. Modern electronic devices such as a mixers, and professional places for powdering crops like bangakgan take its place. However, pestles, which emulate the mechanics of bang-as still have limited use today in pharmacies to powder medicines. Also, in museums bang-as on display inform people of their traditional usage and high quality. Bang-a is valuable to our cultural heritage because it not only has a high quality in scientific field but it also has encouraged the development of a cooperative Korean society.