The path along which soonjung comics* in Korea have come

IN NOVEMBER, 2007, “Naver,” the largest portal site in Korea held an online vote for the best Korean comics and animation. Among the comic books nominated during the contest, Gung(Palace) and NABI, which are famous comics, ranked at the top. The result exhibits the popularity of soonjung comics these days. However, soonjung comics in Korea had to come a long way to reach where they are now. The restless efforts of authors and support from female readers have helped create and develop the success of soonjung comics. Now, settled as a major genre of Korean comics, soonjung comics are opening doors for women to communicate their opinions.

*(soonjung comics: comics targeting female readers and usually written by female authors)

Development of Comics in Korea

Throughout the last decade, appreciation of comics in Korean society has changed greatly. In contrast to the previous belief that reading comics is juvenile, it is now viewed as professional genre for all ages. Lee Yun-ji (Sr., Dept. of History), a member of Manhwasarang (a *dongahree* of comic lovers), confesses that she often had trouble with her parents because of her passion for reading comics. “My mother thought comics were a waste of time. She thought reading comics are uneducational and I should read serious books instead,” Lee says. Yet recently, people’s perception towards comics has shifted positively. Various events related to comics, such as SICAF (Seoul International Cartoon and Animation Festival) and BICOF (Bucheon International Comics Festival), are enjoyed by a large number of citizens. Even the Korean government supports such events because it recognizes comics and animation as a major source of future economic development.

Park In-ha (Prof., ChungKang College of Cultural Industries)

Contemporary comics of Korea can be divided into two main categories, according to their consumers: males and females. While the initial works of comics were usually for men, comics for females came out a few decades later. They are generally called soonjung comics in Korea. A comic critic , Park In-ha (Prof., Dept. of Comic & Cartoon Creation of ChungKang College of Cultural Industries), indicates that “Soonjung comics had a large number of great authors and memorable works in Korean comics, especially after the 1980s.” Though it started as a minority in the beginning, soonjung comics are now gaining huge popularity and stand as a major category of Korean comics. Such existence and popularity of these comics provide balance in the comic circle of Korea as they represent a viewpoint of women, which had been disregarded. Furthermore, soonjung comics are also significant in that they reflect the growth of women’s voices in the society.

Beginning of soonjung comics

Soonjung comics first appeared in Korea in the late 1950s to 1960s, but they contained certain limits. Park characterizes comics of that time as implying moral messages of good and evil, targeting little girls. The stories were usually suitable for a family to enjoy together.” During that time, female characters were mostly featured in a traditional image of women: naive, quiet and submissive. At this time, the comic circle was basically led by male authors, with a few pioneer women cartoonists such as Min Annie, Song Soon-hee, and Uhm Hee-ja. Shin Eel-suk, a renowned comic book author, recollects how the comics were like in her childhood. “When I was young, comics for girls had similar storylines, such as A Little Princess, Most comics were drawn by male authors then, even for the soonjung comics.”

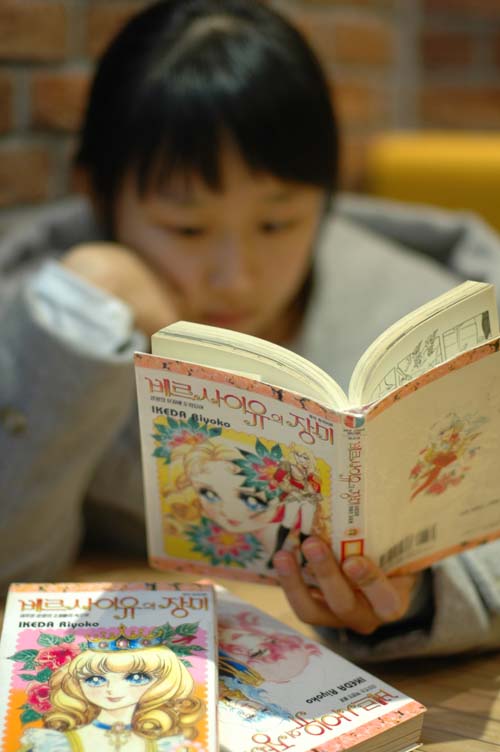

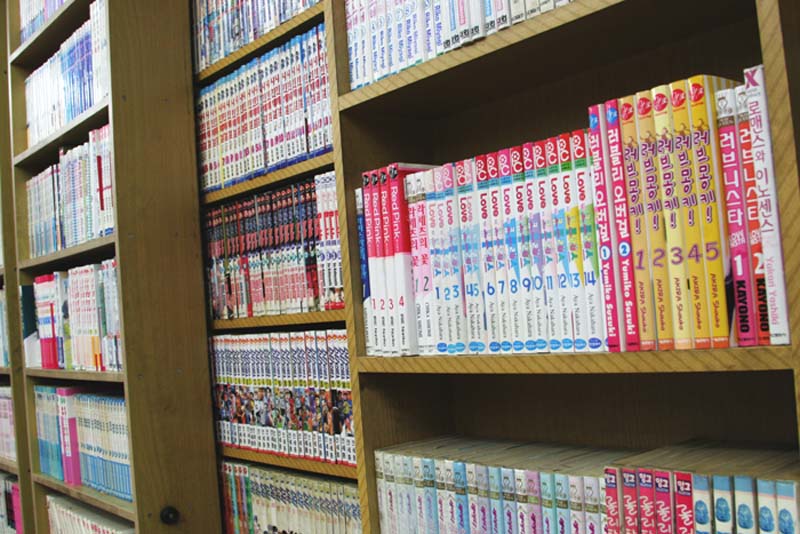

In the 1970s, the dictatorial government implemented a strong censorship policy over publication including comics, which as a result interrupted the development of soonjung comics. However, Japanese comics for females were imported in the late 1970s and functioned as a stimulus for the revival of Korean soonjung comics in the 1980s. Famous comic books like The Rose of Versailles or Candy Candy arrived in Korea at that time. Park says “There were a lot of large-scale, imported Japanese comics, which had influence on Korean comics in the next decade.”

Revival and settlement of soonjung comics

Revitalization of soonjung comics began in the 1980s when female authors such as Han Seung-won, Hwang Mi-na, Shin Eel-suk, Kim Hye-rin, Kim Jin, and Kang Kyung-ok actively created comics. Soonjung comics of the 1980s have taken two significant steps. First, the comics were meaningful in that they were created by and targeted to women. “Unlike the works of the previous periods, soonjung comics in the 1980s were directed by female authors. In addition, they were drawn in a way where women could feel more emotions. While comics for male readers emphasized more on the development of the entire story, soonjung comics focused on describing vivid emotions of the characters. We can say that ‘real’ comics for females finally appeared during this period,” interprets Park.

Second, comics in the 1980s diversified the content of Korean soonjung comics by dealing with grave and epic themes. Comics like Swamp of Phoenix (Hwang Mi-na) or Four Daughters of Armian (Shin Eel-suk) portrayed lives in social turbulence such as the Reformation of 16th century in Germany or the Persian War. They made people look back on their lives by suggesting serious and philosophical questions: “What is a desirable society?” or “How should one lead his or her life?” Son Hyun-ju (Chief Editor of Issue, a soonjung comic monthly) relates this tendency with the social conditions of the 1980s. “I think comics are the essence of mass culture and thus they keenly reflect the social atmosphere. In the 1980s, people’s demand for democracy and freedom increased more than any other time. They came to doubt what they had learned so far, and challenged the dominant social realities. Comics of that time were influenced by such ideas, and thus expressed their characters’ agony with life and society,” she explains. Contrast to the old belief that women are not concerned with topics related to social affairs, the popularity of these new types of comics showed women’s interests toward serious subjects.

Voices of female readers

The advent of female-led comics manifested women readers’ emergence as a major class of consumers in the comic market. In the late 1980s to 1990s, demands of female readers for the growth of soonjung comics in both quantity and quality increased. The publication of the first comic “magazine” for women, Renaissance, in 1988 satisfied those demands.

Female characters of the 21st century

Since the 2000s, comics in Korea are having dynamic reforms. Such tendency is especially evident in terms of female characters. In general, female characters in Korean comics have become more and more active compared to the past. “In the soonjung comics of the 1990s, romance was the main subject. Even though it is still a major subject of soonjung comics, the difference exists in the relationship between male and female characters. Girls in the comics of the 1990s were usually passive while boys took the initiatives in their relationships,” analyzes Son. For instance, in many storylines of those comics, a girl is kissed by a boy by coincidence or only because the boy likes her (anyway regardless of her feelings in both cases) and finds herself fated to love him. Such structure shows that a man still led the relationship between the couple.

Yet, comics published in the 2000s show different sorts of leading female characters. Comics such as NABI or CIEL illustrate strong female figures. In the world of CIEL, female magicians (referred to as “witches”) are naturally born with far

The recent revolution in female characters is related to the altering social perception toward women in Korea, reflecting social changes such as the growth of career women. More importantly, the fact that active female figures are accepted by readers is encouraging. “It is meaningful that people are noticing that featuring only weak females is unfair, in contrast to the past,” says KimGoh Yeon-ju, who teaches “Gender Equality and The Future Society” at Yonsei Univ. “As the number of female cartoonists increases, they can draw images of women that are more positive than before,” she adds.

* * *

The Bank of Korea is planning to issue fifty thousand bills in 2009. For the new bill, a portrait of Sin Saimdang, who represents the traditional image of Korean women, was selected. This shows that Korean society still hold conservative ideas for women, despite the recent revolution of female images in comics mentioned above. Yet, looking back upon the path soonjung comics has walked so far, we can find some possibilities for change. Korean soonjung comics began their journey from a male-dominant comic circle to an equal balance with female voices being heard. . Novel experiments in female characters of the 21st century shows that self-portraits of young females are changing in a more active way. Given the fact that comics, as an art, interact with society, such new tendency of current comic circle is significant. Why can't soonjung comics of this century be a bridge for a new and better society?

“Any change for men?”

New types of male characters in soonjung comics

What have occurred to men in soonjung comics, while women figures underwent dramatic changes? It seems that male characters are not exceptions to transformation. In general, male figures in comics of the 2000s express their feelings more easily and are more sympathetically to women than before. “In Full House of Won Soo-yeon, the hero “Ryder” seems like a perfect and masculine guy. Girls in the 1990s must have liked that kind of man. However, heroes in more recent comics are not like Ryder anymore,” says Lee Yun-ji. Son, also exemplifies that “A boy named ‘January’ in CIEL takes care of the heroine and supports her. Nowadays, the number of male characters who become good companions of females is increasing.”

Interview

Shin Eel-suk (comic author, ex-chairperson of KWCA (Korea Woman Cartoonist Association)

| ||

| Shin Eel-suk |

Annals: As a cartoonist, what do you think makes comics most attractive?

Shin: The quality I love about comics is that they are fixed on a stable screen. Unlike TV programs or video files, I can go back to any page I want to see at any moment. This allows people to take their time and breathe with the author while reading a comic, creating the “rhythm of comics.” People are apt to think there is no rhythm in comics because they provide no sound. However, there exists a moment in which the rhythm of the author and the rhythm of the readers meet and that is the most charming moment of reading comics.

Annals: In your work *Four daughters of Armian*, each of the four heroines has distinctive characteristics even though they are sisters. Especially in the cases of “Manua” and “Shari,” how could you create such strong female characters?

Shin: I think every character in comics is a reflection of the author. When I was young, I was quite defiant against the reality that women have to endure sacrifice for men. For example, my parents had two daughters and a son, and I and my sister had to give up going to college for the sake of my brother. I did not like the notion that women should sacrifice their education for the sake of men. Such sacrifice applied to many other women of the time. There was a market near my house in Busan, so I grew up seeing a lot of rough *ajummas* in the market. I always thought they could have led a more liberal life if they had been properly educated. They were strong enough to carve out their own future but they were given the opportunity because they were women. Perhaps my objection toward such realities was reflected in those characters.