A look into how our bacteria keep us alive

DR. ERICA Sonnenburg and her family do not mind petting their dog and subsequently eating without washing their hands. In fact, she encourages us to do the same: to expose ourselves to bacteria in order to nurture our gut microbiota, which was recently discovered to be one of the most vital parts of the human body.

Breaking down the gut microbiota and its functions

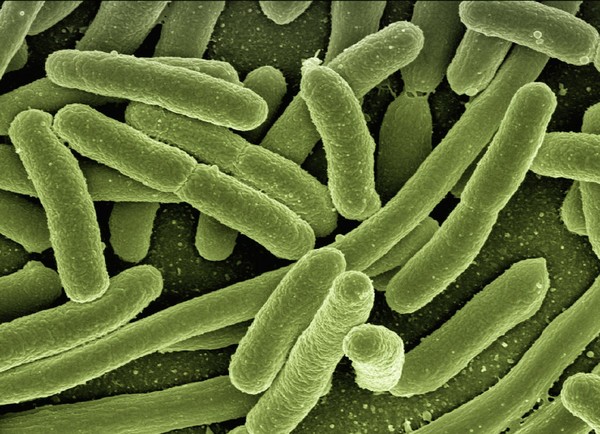

The gut microbiota is the complex of bacteria and other microorganisms that inhabits the body’s gastrointestinal (GI) tract, or guts. However, most of the bacteria are concentrated in the large intestine. In an interview with The Yonsei Annals, Dr. Erica Sonnenburg (Senior Research Scientist, Dept. of Microbiology & Immunology, Stanford Univ.) expressed that, for many years, there was not a lot of understanding on the function of the gut microbiome. However, Sonnenburg has been a part of the recent pioneering research that shows how the gut microbiome* is wired into various aspects of our biology to the extent that they are indispensable to the human body.

As part of the GI tract, the gut microbiome does its share during the process of digestion. For instance, our gut bacteria produce enzymes that break down plant fibers that our bodies cannot digest—a process that generates molecules that later flow throughout the bloodstream. There is evidence that these molecules can positively coordinate our metabolism. For example, three species of bacteria are known to synthesize vitamin K2, which helps lower cholesterol levels and, thus, lower the risk of cardiovascular disorders**. We can say the gut microbiome does not let the true nutritional value of plants go to waste.

Another discovery has been the gut microbiome’s connection to mental health; the link has been named the “gut-brain axis.” Besides proteins, other chemical compounds are produced by our gut microbes, including neurotransmitters—the chemical messengers between nerve cells. For instance, the gut microbiome manufactures 95% of the body’s supply of serotonin. This neurotransmitter influences mood, anxiety, and happiness as well as the GI tract. Not only that, vitamin B, which gut bacteria produce during digestion, also reinforces energy levels and brain function. As a result, the gut-brain axis shows not only the connection of the guts to the brain but also the convergence of the body’s functions***.

Sonnenburg adds that another intricate relationship that the gut microbiota maintains with the body is with the immune system. Gut bacteria are monitored continuously by the immune system to prevent their influx into the bloodstream and tissues. Thanks to the communication network between the gut microbiome and the immune system, the walls of the gut remain impermeable, which prevents immune responses that can result in inflammatory bowel disease, sepsis, and other adverse reactions. Considering the magnitude of the gut microbiome's influence, it is no surprise that this bacterial complex is gaining status as an organ system.

The gut microbiome’s imminent extinction

Unfortunately, industrialization and modern eating habits have been deteriorating our gut microbiomes. A study conducted by Sonnenburg shows that the gut microbiomes of the Hadza people—modern-day hunter-gatherers from Tanzania—display a diversity of bacteria species that allude to the microbiomes of our ancestors. “Sometimes I like to think of the microbiome as an ecosystem. If you look at a hunter-gatherer's gut microbiome, it looks like a lush, ecologically complex rainforest compared to a Western gut, which is more homogeneous and deteriorated. In other words, we have lost diversity in terms of the species and functionality of bacteria in our gut." One of the contributors to the deterioration is antibiotics, which indiscriminately kill good and harmful bacteria; a dose of antibiotics can alter the microbiome and cause imbalances. However, the most notable force of deterioration is diet; fast and convenience foods have promoted low-fiber diets for decades to the extent that their effects may now be irreversible. Accordingly, Sonnenburg adds that industrialization and the gradual deterioration of the modern gut correlate to the increasing incidence of chronic diseases. "Long term diet studies have shown that populations that eat a high-plant diet have a lower incidence of chronic diseases. For instance, obesity does not exist in [hunter-gatherer] populations but has become a persisting problem in contemporary society.”

So, what can we do?

Managing diet is one of the major ways to nurture the gut microbiome. Sonnenburg and her husband, Dr. Justin Sonnenburg, coined the term “Microbiota-Accessible Carbohydrates” (MAC) in their book, The Good Gut, as a necessary dietary element.

Sonnenburg explains that there are two categories of carbohydrates. One of them constitutes small, sugar-type carbohydrate molecules that are easily absorbed and commonly found in juices, sweets, or highly refined foods. These simple carbohydrates can also be found in white bread and white rice, and they essentially raise blood sugar, cause weight gain, and possibly lead to type 2 diabetes. On the other hand, the term “MAC” refers to the second type of carbohydrates, which are highly complex and found in plant matter such as roots and vegetables. Unlike simple carbohydrates, these MACs are not absorbed nor digested as easily, so they travel to the end of our digestive system—our gut—where they get fermented into beneficial compounds by bacteria.

When asked about protein-based diets, Sonnenburg shares that we are already eating an amount that exceeds what we need. “Proteins are easily replenishable; even people that eat vegetarian or vegan diets are not protein-deprived.” Thus, she suggests that people should not exclude carbohydrates from their diets and “instead think about eating a diet that is rich in complex carbohydrates, which we are not having enough of in the industrialized world.” Fermented food is also another beneficial source of food for the gut microbiome. When bacteria ferment, they consume many of the simple sugars; in a way, bacteria pre-digest and lower the glycemic index**** of the food we consume.

Another way we can help our gut microbiota is, interestingly, through exposure to external bacteria. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, however, has normalized sanitization, which directly contrasts with coming in contact with bacteria around us. Sonnenburg acknowledges the use of sanitization to remove harmful microbes, but believes that we should find alternative ways to expose ourselves to helpful microbes. She tells us one way her family balances exposure and prevention. “My family has a dog, and when we bring him in after letting him dig and roll around, we don’t worry about washing our hands after petting him before eating because the risk of our dog bringing in a pathogenic***** microbe is low. But if we were to go out in public, then we would definitely wash our hands. We just have to be making these calculations constantly." In light of our limited exposure to external bacteria, Sonnenburg once again emphasizes the benefits of consuming fermented food. “I think fermented foods are a great way to [expose ourselves to microbes] because it’s a way to ingest bacteria that we know aren’t harmful and are likely to be beneficial.”

* * *

To help our gut microbiome does not mean we should return to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. We have the research and technology that will possibly find even more effective ways of nurturing our gut microbiome. But most importantly, we now have the knowledge to reorient our relationship with bacteria. Sonnenburg insists that “most microbes are completely benign or potentially beneficial,” and many of these bacteria make up a part of us. It is fair to say that self-care now encompasses both a little more than us and a little more of us.

*“Microbiome” and “microbiota” are used interchangeably in this article.

**Frontiers in Microbiology

***Monitor on Psychology

****The glycemic index indicates how carbohydrates affect blood sugar levels. A low index suggests lower or slower increase in blood sugar.

*****Pathogenic: Describes something capable of causing disease