Global warming contributes to increasing damage from typhoons

ADRIENNE (ALIAS) positioned the trash can carefully on her family store’s outdoor area, trying to remember where the puddle had formed during the last typhoon. The water had dripped through the floor to the fitness center below them, and the owner had called Adrienne’s in panic and fury, demanding that the leak be fixed. With no money to fix the problem, her family resorted to bailing out the water whenever possible. Yet, this summer’s 50 day-long monsoon and unusual succession of strong typhoons had worsened the leak. With typhoons becoming stronger every year, the leak would only grow worse every summer until it was fixed or break out in a flood.

The rise

Despite the recent successive typhoons, the number of storms occurring near the Korean peninsula has not necessarily increased. Typhoons that affect Korea are formed in the Northwest Pacific region next to Southeast Asia and the Philippines, home to one-third of the world’s tropical cyclones*. According to Korea’s National Weather Service (NWS), from 1981 to 2010, an average of 25.6 typhoons per year reached the Northeast Asian region; from 2001 to 2010 it was 23; and from 2011 to 2020 (considering 2020’s typhoons 10 in total as of mid-September), 24.8.

What has changed due to global warming, however, is the severity of these storms. Tropical cyclones are powered by excess energy produced when water vapor rising from warmed seawater meets and congeals with cold atmospheric air. Thus, the warmer the sea and the cooler the atmosphere, the stronger the cyclone. Korea’s typhoons have been significantly more severe in late summer and autumn as the Northwest Pacific’s surface temperature becomes hottest during August and September**. Professor Moon Il-ju of Jeju University’s Typhoon research center states in an article contributed to KBS that one of the forces preventing typhoons from directly impacting Korea is the jet stream, a fast-flowing air current flowing west to east originating from temperature differences between high and middle latitudinal regions. Due to global warming, data analyses have shown a clear weakening of the jet stream and rapid rise of sea surface temperatures between Korea and the Northwest Pacific region**.

In May 2020, the Korean NWS declared that they would be adding a stronger category to their former typhoon ratings: a “super strong” category (winds exceeding 194 km/h) above the previously highest “very strong” (now 158-194 km/h)***. The change was made as NWS data showed that “very strong” typhoons occurred with increasing frequency so that over half from 2009-2018 fell within this category. With the new category, half of those “very strong” typhoons would now be considered “super strong****”.

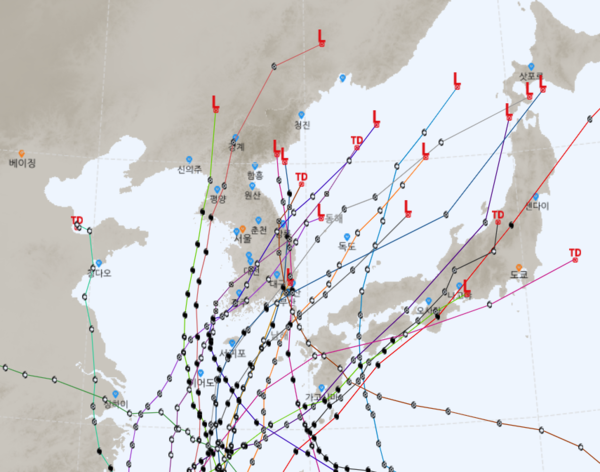

Global warming has also been affecting the trajectory of typhoons as to bring them closer to Korea and previously less affected areas. All four typhoons that hit Korea this summer rose from the southern sea and came up the peninsula in straight, almost parallel lines instead of curving away towards the east as they had usually done before. This phenomenon comes from the North Pacific High-Pressure Area expanding more towards the northwest, pushing typhoons to travel from South to North Korea rather than towards Japan. Climatologists are unsure whether this change is due to natural cycles or human-induced global warming, but statistically more typhoons have been affecting Korea despite their decreasing numbers in this geographic region, a trend likely to continue for the next several years*****.

Compounding (nuclear) conundrums

These trends explain the three typhoons Bavi, Maysak, Haishen—categories “very strong,” “super strong,” and “super strong” respectively—that battered the country in a short span of two weeks this August and September. They also foreshadow that this rapid succession of storms is likely to be repeated in the near future. As higher atmospheric temperatures from global warming mean that more moisture will be stored in the air, both annual monsoons and typhoons are more likely to carry more rains******. Such a rapid succession of deluges would make recovery from natural disasters more difficult, increasing chances and damage from landslides and flooding.

The typhoons also pose an increasing risk to the 24 nuclear power reactors dotting the South Korean coastline. 18 of these are located on the eastern shoreline, where typhoon influence used to be less common. This summer, however, minor panic ensued as Maysak and Haishen made 6 turbine generators in the Kori Nuclear Power Plant stop producing power, the first time a typhoon forced nuclear powerplant systems into a halt since 2003’s Maemi. The strong waves from the typhoons allowed salt to touch the internal water supply line, which automatically caused the reactor to stop and the diesel generator activate. This system is all part of a backup system to keep the reactor cooled and technically is not considered an emergency*******.

However, the Korea Federation of Environmental Movements has expressed strong concerns that “there is no guarantee another natural disaster in a nuclear reactor concentrated area would not result in an incident like Fukushima,” and that “the government must accelerate de-nuclearizing energy and revert to recyclable energies********.” The Kori plant is particularly vulnerable to the stronger typhoons’ new trajectories as it is the only nuclear power plant on the eastern shore that faces south, leaving it vulnerable to direct impact.

The government and scientists, however, have voiced against this call for sudden change, claiming that recyclable energy is even more vulnerable to extreme weather as solar panels and windmills would be forced to suffer long pauses or physical damages due to such inclement weather; the current system of mixing multiple energy sources is more stable for the time being. Kori plant representatives said that they plan to cover all affected devices with another protective case*********.

The unusual and unexpected

The only extant way to minimize damage from typhoons is to make accurate predictions and prepare accordingly. Despite the daily slander targeting the NWS, it is constantly making efforts to improve its forecasts; Korea is the 9th country in the world to have its own independent Weather Prediction Model, which would allow immediate improvements to the system and more detailed observations. This model, however, has only been operating since this April and thus has little confirmed credibility and established data. And even with more advanced technology, there are limits on how accurately predictions can be made on monsoon rains and the exact expected trajectories of typhoons down to kilometers—especially when climate change is creating unprecedented weather patterns.

The NWS has been attempting to make its typhoon forecasts more accurate. For example, the new typhoon criteria sort storms by strength instead of size, as how strong a typhoon is can be different from its range. Yet, there is clear area for improvement in broadcasting to all afflicted parts of the nation; Dokdo and Ullengdo, easternmost residential areas of Korea, suffered immensely from the typhoons but mostly went unreported in major national broadcasts until the aftermath**********.

* * *

After Haishen roared past the country on September 8, rumor circulated that an eleventh typhoon was forming to strike Korea. No meteorological centers observed the storm until September 16; in the end, the storm—named “Noeul” (sunset)—is said to veer towards Vietnam. Still, the possibility that more strong typhoons would impact Korea in 2020 remains, as three impacted the country from September to November last year. People are weary from psychological and economic damages of three consecutive typhoons amid increasingly unpredictable weather. They are holding their breaths for the next storm.

*Tropical cyclones: also known by other names such as tropical depression, tropical storm, hurricane, typhoon, or simply cyclone

**KBS

***For comparison, a category 4 hurricane on the Unites States’ Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale is 130-156 mph (209-251 km/h)

****JTBC

*****The Hankyeoreh

******The Hankyeoreh

*******Donga Ilbo

********Korea Environmental Newspaper

*********Donga Ilbo

**********Gyeongbuk Mail