A pandemic story from Colombia

"RIGHT THEN and there, I saw two men get their throat slit and fall to their knees for the uniform they wore," narrates Carolina*; what she witnessed reflects what thousands of Colombians have seen during the massacres that occur in the country every year. Although the occurrence of these mass killings stretches back decades of an internal conflict, with the COVID-19 pandemic has come an unprecedented spike in massacres.

What is happening?

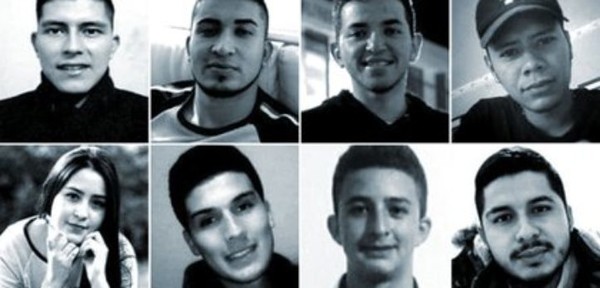

Massacres returned to mainstream news in Colombia when two teenagers of ages 14 and 15 were assassinated on August 11, and eight were massacred four days later in a different region. These two incidents were followed by more. On September 7, three massacres occurred in a single day in three parts of the country. As a result, August and September witnessed 11 and 16 massacres, respectively. These numbers have been alarming; according to Indepaz**, they add to a statistic of approximately 263 victims from 66 massacres in 2020 alone—and counting—compared to 36 in 2019. Unfortunately, massacres have not been the only killings. Colombia has also been experiencing a staggering number of assassinations of social leaders and ex-guerrilla members; 221 leaders and 47 ex-militants have been assassinated this year as of September 30***. Massacres and politically motivated-killings had been steadily on the rise, but a spike in 2020 only points to the pandemic as an accomplice.

Why do massacres happen in Colombia?

In order to understand today's violence, it is vital to understand the bloodshed of the past. As one of the leading exporters of cocaine, Colombia is plagued by violence that facilitates drug trafficking. Although drug magnate Pablo Escobar and cartels paved the way for a drug-ridden history back in the 1990s, guerrilla forces intertwined the drug trade with political conflicts. The FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), the largest group in the country's history, became one of the most influential organizations with drug trafficking ties. Since its establishment in the 1960s, the FARC advocated for Marxist-Leninist ideals, such as the equal distribution of wealth, which conferred them both local and international support, most notably from Cuba’s Fidel Castro administration. However, governmental attacks against communists in the 1960s drove the group out to remote regions in Colombia. This exclusion incentivized the FARC to resort to drug trafficking and violence as a means of upholding their political and social goals, instigating decades of conflict between the group and the Colombian government. The vicious cycle came to an end—or was thought to—when a Colombian Peace Deal began in 2012 between the FARC and the government. Dressed in white, both parties' leaders carried out talks for peace until 2016 when the deal was finalized, and the FARC officially disbanded afterwards in 2017****. The agreement addressed issues from drug trafficking to territorial control, paving a promising solution to the armed conflict. Little did the world know that the deals would be at the root of today's violence.

In an interview with The Yonsei Annals, Leonardo González, a coordinator of Indepaz's human rights watch division, explains that we must first understand how the Peace Deal's inadequate implementation is at the base of the 2020 massacres. "The government is not present in many vulnerable regions, and if it is, it’s present through the military and not socially nor politically. Therefore, the regions that were once under the FARC's rule are now being fought over by dissident groups and other armed organizations because these areas are rich in resources or are drug-trafficking routes." Unfortunately, the convergence of gangs, dissidents, and FARC residual groups in disputed areas has trampled over the civilians that returned and currently live there.

Carolina, a 47-year old woman, who was born into, and continues to live, in the crossfires of Colombia's violence, detailed her experiences in disputed zones in an interview with the Annals. "I come from the fields, and it was tough living there. My family lived in between armed troops—the guerrillas on one side and the paramilitary troops on the other. You could not side with anyone because the other group would kill you." Without governmental protection, thousands of people like Carolina have been forced to stay silent. The justice system further worsens the lack of impunity. González claims that "Colombia has over 90% impunity over crimes, and this guarantees to armed groups that they can do whatever they want and go unpunished."

Where COVID-19 comes in

Although Colombia's internal conflicts have played a significant role, a 200% increase in killings in 2020 has also been attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic. The country's infection rate does not help the case; Colombia currently stands, as of October 9, among the top 5 countries with most infections*****. In response to a fast and untraceable outbreak, Colombia enforced a nationwide lockdown for five months. Unfortunately, the absence of central government authorities, as quoted by González, has allowed armed groups to easily overpower local leaders and take over vulnerable communities. In an interview with Infobae, Javier Cortés—leader of the Awá indigenous group—describes how armed groups took over his community after driving him out through an attempted assassination. "After driving me out, the groups started to enforce quarantine, but civilians did not adhere to the lockdown, not because of a lack of conscience but because they did not want to starve to death, so all civilians were threatened if not killed.” Quarantine enforcement as a form of power has been witnessed across the country as well. In 2020, a total of 79 pamphlets threatening death in the case of quarantine violations have been published, and several groups have already claimed responsibility for massacres on the pretense of enforcing the health protocols******.

As expected, armed groups have been enforcing quarantine for their benefit. In another interview with Infobae, Luis Fernando Trejos, a Colombian post-conflict investigator, hypothesizes that groups are taking over as health authorities to consolidate their power while their finances suffer from limited drug-trafficking due to the pandemic. "The groups also believe that maintaining infection numbers low will keep governmental authorities from coming to their territories."

However, staying inside has become an even bigger threat to some. González explains that a quarantine doubly enforced by violence and a virus has "kept targeted social leaders in their homes, making them easier targets while their communities become more defenseless to violence." This phenomenon is reflected in the statistics, too; there has been an 85% increase in leader assassinations, with some local statistics ranging between 150% and 400% increases*******, placing Colombia first in leader assassinations worldwide. The threat of both the virus and the armed groups reflects a grim choice many Colombians leaders and civilians have had to make—to risk contracting the virus, to starve, or to have a higher chance of getting killed.

Where hope lies

Despite growing worries, not all hope has been lost. "We knew a signed deal would not guarantee peace, so at least we know there is work that can be done," states González. He emphasizes that Colombia needs a government that is integrated politically, economically, and socially across the entire country to address the deal's implementation. "People in rural regions cannot keep seeing the presence of the government through a soldier that carries a rifle and wears camouflaged clothes." Moreover, González seeks international support. "The international community needs to know what is happening and pressure the government because the infection ranking is not the only one that Colombia is topping."

* * *

As the world continues to grapple with waves of the pandemic, countries like Colombia are being left behind by internal conflicts; their governments face a triage: what should be dealt with first? Which issue should be prioritized? "I am not afraid of the virus," says Carolina. "I am afraid that the virus will be seen as more of a threat than the killer near my house.”

*Carolina is a nickname chosen by a victim who has wished to remain anonymous.

**Indepaz is a Colombian institution that studies development and peace.

***Pulzo

****BBC

*****Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center

******DW News

*******El Tiempo