An essential designer and a responsible problem-solver

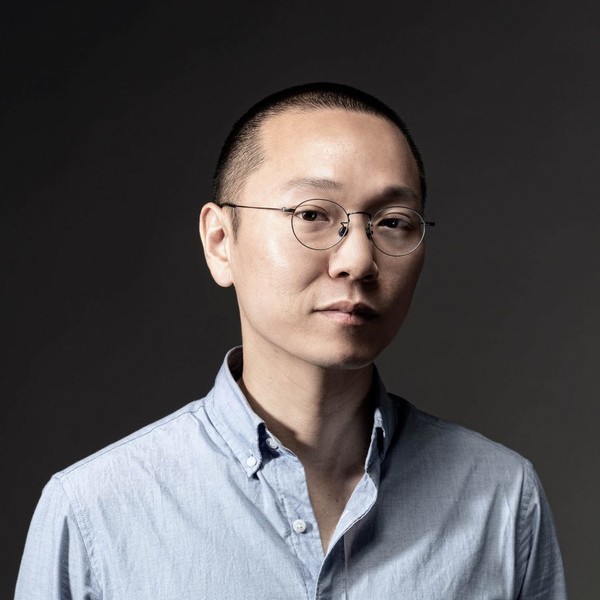

ARCHITECTS MUST maintain a delicate balance between form and functionality in their work. They are tasked, not just with designing buildings, but also with shaping a fundamental aspect of how we live and interact with one another. The Yonsei Annals met with the architect Kim Lee-hong (Class of ’99, Dept. of Arch. Eng.) at his atelier, Leehong Kim Architects, to learn more about this unique and challenging profession. Having received the Korean Young Architect Award in 2018, Kim says his career is still developing and that he has a mind for tackling new challenges. In the meantime, he teaches at Hongik University’s Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Design in addition to his work as an architect. Kim shared with us his views on architecture as well as his, still-developing, design philosophy.

Annals: What led you to become an architect?

Kim: As a kid, I loved experimenting and making things by hand. I was the kind of boy who liked puzzles, Legos, crafts, and unusual three-dimensional figures, so basically, anything I could work on with both hands. And when I turned fourteen, I had the chance to study abroad in the U.S for about a year. As part of the school curriculum, I took a class on industrial design where I learned basic drafting techniques and visited wood shops to try woodworking. The experience has had quite an influence on me since I dreamed of being a carpenter back then. But in the traditional Korean primary education system, there wasn’t a course like Industrial Design, which seemed so perfectly suited to my interests. My time in the U.S. convinced me that I wanted to design and construct large buildings and led me to pursue a major in architectural engineering.

Annals: How important is the relationship between a client and an architect?

Kim: The relationship between a client and an architect is very intimate, so I try my best to accept my clients’ requests and reflect their needs in my buildings. Many clients usually have particular designs in mind, and it is both a fruitful and intellectually challenging experience to materialize their needs. That being said, not many clients make entirely unreasonable demands of me, such as asking me to design a building like DDP at Dongdaemun, which is markedly different from my architectural style. Most clients have made their request after reviewing my admittedly limited portfolio, and to my gratitude, have expressed their appreciation for my style of work. So, I think there is a lot of room for me to communicate with them to accommodate their requests and find a middle ground between their needs and my designs. I actually tend to learn a lot from my clients, who are often a source of novel and unexpected insights. Ultimately, I think the role of an architect comes down to solving the different contextual problems each client has. Unless you are constructing a building in the middle of nowhere, like an empty stretch of the Sahara Desert, every architect has to plan their designs bearing the surrounding contexts* in mind, and it is the clients who usually pinpoint these problems and provide general guidance to an architect. What’s more, clients are often the most important supporters of architects. Renowned architects usually gain their notoriety through conducting numerous projects with big clients like major companies, who helped them establish their foothold in the field. Maintaining a good relationship with our clients is an integral part of our job.

Annals: What aspects of a design do you consider most when planning?

Kim: I spend the most time thinking about circulation. Circulation in architecture refers to the pathways people move through in space and how they interact with the physical space itself, as well as other people sharing that space. So, circulation takes into consideration elements such as the purpose of the building, the number of occupants, direction and length of travel, and frequency of use. In my spare time, I like to experiment with different types of circulation to make interesting interactions happen in one place. For instance, I can make people circulate a space or have them meet naturally at one spot. Apart from the circulation inside the building, I also care about how my buildings would look in the larger context of the surrounding landscape, whether it stands out or blends in, though I personally prefer the latter. Buildings with unique design do have merit as landmarks, but I like to respect the surrounding context and incorporate little twists which do not flaunt themselves too much. I think this partly reflects my introverted character and personal preference for simplicity and moderation. Still, my architectural style is always open to change as I do more projects going forwards.

Annals: You mentioned your general architectural preference. Are there any more specific preferences of yours?

Kim: When I conduct a project, I prefer working with constraints rather than starting from scratch. Although constraints like the budget, the client’s requirements, and the context can very well be limiting factors to an architect’s freedom and creative thoughts, I find that contextual constraints help me find reasons and meaning for my work. I recently worked on a single-family household in Hongchun, and my client, who had a belief in Chinese geomancy, made specific requests about the angles of the inner space, about having a particular scenic view through the window, the location of the entrances and doors, and internal circulation. Some of his requests, such as locating the main bedroom at the entrance, were quite unconventional for a residential building and resulted in inefficient uses of space, but I found this project very interesting to work on. Speaking of constraints, when we start construction, we often face many unexpected topographic challenges that were not apparent during the planning stage and changing plans can be very stressful depending on the severity of this unexpected problem. But instead of viewing this as an obstacle, I try to use these constraints to add uniqueness to the design. When I began the Dan project, while excavating through surface soils, we identified a huge bedrock that came from a neighboring building and chose to reveal its texture as a part of our interior wall instead of fully covering it with cement.

Annals: Many of your works incorporate mathematical proportions like the golden ratio. Is there any risk of your designs becoming monotonous if you focus too much on preserving proportionality?

Kim: Achieving the golden ratio is something many architects have strived for throughout history, including Steven Holl, whom I worked with in the U.S, and employing a mathematical ratio in architecture can be aesthetically pleasing. I don’t necessarily think preserving proportional beauty leads to monotony in design because there are numerous ways in which the unique patterns of different ratios can be expressed. What’s more, the scale of a building, when combined with this proportionality, can really leave a lasting impression. Proportional beauty is often what immediately captures your attention when looking at a building.

Annals: When you design, you have a habit of making your models with your hands. What is its merit compared to using computer programs?

Kim: I think my preference for making models by hand is due to my way of thinking and how I visualize 3D shapes. I find making models by hand much more intuitive and less restrictive when it comes to transmitting what is in my mind into the real world. Despite its expedience and time-saving capabilities, computer rendering often hinders my creativity because you always need to provide a specified input to get a desired output. Working by hand, I can be more flexible in my thinking and maybe get unexpected inspirations from the tactile creative process. By allowing myself to cut, attach, remove, and move different shapes more freely, I can think outside the box more easily, and it often yields better results. Moreover, the impact of lighting and shadows, which are integral parts of architectural design, is easier to see through hand-made models.

Annals: How was your experience working at Samwoo Architects & Engineers and Steven Holl Architects?

Kim: I worked at both offices for 3-4 years, and they were quite different in nature, so I was lucky to have the opportunity to work for both places. After I was discharged from the army, I worked at Samwoo Architects & Engineers, which was a large architectural firm with nearly a thousand staff. Their main work was more geared towards designing larger buildings like corporations, research institutions, city parks, hospitals, and university buildings. We mostly worked as a team and were in charge of very specialized tasks. For instance, some people worked on the façade** while others worked only on the core***. Due to the specialization of labor, it was difficult to experience the entire design phase and construction process in one project. As I had only recently started my career back then, there was also little chance for me to have a direct influence on the design process. After I got married, my wife and I moved to New York, and I submitted applications to a few architectural offices, including Steven Holl Architects. This time I was looking for a smaller architectural firm where I could be more directly involved in the entire phase of design and construction. Before I entered Steven Holl Architects, I wasn’t well acquainted with his work nor did I personally like his style though I knew how famous he was in the field. During the job interview, I realized that my habit of making models with my hands really appealed as a strength because Steven Holl always uses hand-sketches and watercolors to visualize his work. Due to this personal preference for working with his hands, he was also heavily invested in making models by hand. I think my experience at Steven Holl was a better learning experience for me because I was able to receive one-to-one, constructive feedback from Steven Holl every day and trained rigorously in the fundamentals of design. I also got to know Steven Holl better in-person and enjoyed the other personal interactions I had with people there.

Annals: When you conducted New York’s 57E130 NY Condominium Project, what was your design priority?

Kim: As its name would suggest, the project was a condominium**** in New York, specifically East Harlem, which is a residential district in northeast Manhattan. Due to the 1961 zoning resolution, New York’s residential districts are strictly limited in terms of the use of land and the shape of the building. Buildings within the same block can only have a seismic gap of 1 inch, and every façade must align with the roadside, creating this urban grid of Manhattan. I had to find an optimal structure that would stand out, given the limited space. As there was much less freedom in terms of the design of the façade, I emphasized its depth by using differently angled bricks (124, 135, 146, and 158-degree angled custom-made ones) that would cast different shadows under natural light.

Annals: If you could single out one difference in the architectural environment between the U.S and Korea, what would it be?

Kim: One major difference would be the time it takes to receive a construction permit from the state. Normally, it takes only about 2-3 weeks in Korea while in the U.S, the process can be delayed up to a few months. But I think this time-lag is not necessarily a bad thing because it buys us more time to perfect our designs, and architects are constantly under pressure to meet deadlines. Another difference I noticed was the degree of recognition each country has for the need for consultants at the designing stage. Comparing large-scale landmark projects in both countries, when I was at Steven Holl architects and our team worked on the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, our client hired 20 consultants, who were experts in various fields. Although it is common in Korea to hire consultants in essential fields like concrete, landscaping, and lighting, the classifications were much more specific in the U.S; we had a transportation consultant in charge of the parking lot and traffic, a kitchen consultant exclusively offering kitchen design consultancy services, and a façade consultant who helped amend details of our exterior wall design. Although architects are the ones who design the building, we often lack the professional knowledge necessary to guarantee that the construction is suitable for its intended purpose, and I think receiving advice from these consultants can be very helpful. In Korea, it is unconventional for a client to hire that many consultants even for landmark projects, primarily due to the high cost and relatively tight construction schedules.

Annals: The theme of your installation piece at Amore Pacific Museum of Arts (APMAP) was Between Real and Fake. Can you describe this project to us in further detail?

Kim: The installation project took place at the construction site of Amore Pacific’s new headquarters, and I named it Between Real and Fake because the building was actually a mock-up and the real construction site was located right next to it. Mock-ups are typically actual representations of proposed construction built to evaluate planned designs and test construction details like finishing materials. So, for instance, we could test how concrete color and elevator signs look, decide the location of the spring cooler, or test several candidate designs for the ceiling of the main office. But these days, we don’t construct full-size mock-ups or showcase them to the public, given that they are later demolished. But I wanted this 3-story mock-up to look real and wanted to open it to visitors, leaving it solely to them to distinguish between what’s real and fake. Along the entranceway to the mock-up, visitors can see sizable concrete structures and the seeming orange elevator, which is actually another door to an open staircase. Then, their expectations are subverted, and they soon realize that everything in this building is fake. Without a full explanation, some people won’t even notice that the building is a mock-up even after looking around the place. But setting aside any deeper meaning, I just hoped visitors could have a fun experience.

Annals: What do you think are the necessary qualities to become an architect?

Kim: I don’t think there is a set quality necessary to become an architect, but after you become one, you need to have a sense of responsibility for your work. This may sound cliché, but even a very small building built for a purely private purpose can change and impact the way people think, behave, and interact with others, and an architect must feel morally and socially responsible for their role in building it. Also, you have to be able to critically observe and view different objects and social circumstances from multiple perspectives. Architecture is often about creativity, and the ability to think outside the box comes from such everyday practices. Another good practice would be to get into the mindset of thinking like an architect. When you visit a place, try to be curious about the decisions an architect has made, how they solved a location’s unique contextual problems.

Annals: What are your future goals? Are there any specific projects you are interested in?

Kim: I mentioned earlier that my style of architecture is more analogue. But as there is an increasing move towards digitizing architecture, for instance, by incorporating 3D printing, augmented reality, and artificial intelligence, I want to challenge myself by applying new technologies to my working process. I also want to experience different working environments, and it would probably be the best for me if I could travel between the U.S and Korea to conduct projects in both countries. In terms of future projects, I am interested in looking underground for new places of development. Take Yonsei University’s Baekyang-ro underground project and Samsung station’s Bong-eun-sa underground project for example. Although underground projects lack economic feasibility and profitability, I feel the underground still has a great deal of untapped potential, especially in its almost limitless space.

*Context: In architectural terms, context refers to physical and environmental conditions around a particular site.

**Façade: Façade is another word for an exterior wall of a building.

***Core: Core is a vertical space used for circulation, including staircases, elevators, and water pipes.

****More of Kim’s portfolios can be found at leehongkim.com.