Andrés Felipe Solano writes a glimpse into the foreigner’s Korea.

"LITERATURE IS fundamentally a mystery," says Andrés Felipe Solano, "I do not know where my voice comes from, I write to understand it." Born in Bogota, Colombia, Solano never imagined Seoul to be the place that would allow him to flourish as a writer. In college, Solano majored in literature. He then started working as a journalist before writing his first book.

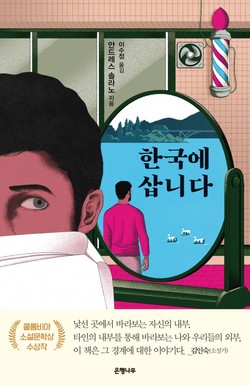

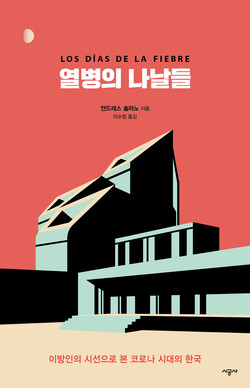

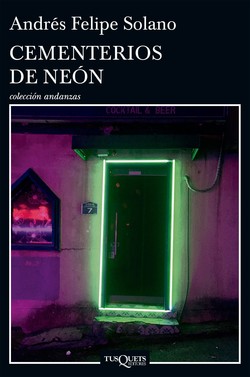

Solano has been featured in the New York Times Magazine, among other renowned publications. Granta Magazine, a distinguished literature magazine featuring Laureates of the Nobel Prize in Literature, selected him among "The Best of Young Spanish-language Novelist." His book, Korea: Notes From a Tightrope, winner of the 2016 Colombian Narrative Library Award, explores the uncertain future of being a foreigner in Korea. The translated version garnered the attention of the Korean public, and Solano kept writing with his new audience in mind. Many of his works place South Korea at its core: Neon Cemeteries told the story of a Colombian veteran that fought in the Korean War returning to Seoul, and his most recent novel From Fever Days recounts the history of the pandemic and the transformation of South Korean society in the span of few months. Solano’s work is a little window into the foreigner experience in Korea.

The Yonsei Annals: When did you realize you wanted to be a writer, and what inspires you to continue writing?

Andrés Felipe Solano: I am a reader. I have always been a reader. In university, I chose to study literature because it was the only degree that let me continue to read. Since I was very young, I started to think I could write stories, just like the books I read. Yet, I did not write any during college or anything of the sort. I only started to write once I graduated and started on my first novel. Writing became my own tool to understand the world. Before sitting down and writing a story, I learned to read the world, and once you do, your mind takes care of the rest. My stories are simply the result of putting my experience and the stories of those around me on paper.

Annals: You mentioned that you learned to read the world. It is a very poetic notion that you "learned to read the world" in order to write—could you explain further what you mean by "reading the world?"

Solano: Reading the world is a specific way of being attentive to what surrounds you. It goes beyond your five senses. It is rather the sensitivity that connects you to the world, one that is developed by reading often. It is not an easy task, and I am not reading the world all the time. I think of reading the world as having the sensitivity that leads you to write. If you are attentive to other people’s stories and connect them to what you know, you can start imagining stories.

Annals: Who are some authors you look up to or who inspires you in your work?

Solano: The book that inspired me particularly was Without Remedy by Antonio Caballero, a Colombian journalist. It is the only novel he ever wrote, and it took place in my city, Bogota. I had already read all the renowned authors like Garcia Marquez, but connecting with his work made me realize that I too could create stories that work within the world I know. It was the first spark that made me realize I too, could create stories and become a writer.

Annals: You started writing in Colombia, but now you live in Seoul. What led you here, and what made you stay?

Solano: I came for the first time in 2008. The ministry of culture invited me for a program called "cultural partnership interchange." They asked several people of different disciplines from all over Southeast Asia and some Latin-Americans to spend six months working in a government cultural agency. I, as a writer, worked within the Literary Translation Institute of Korea. Essentially, my task for those six months as a literary residency was to write a novel. As it was my first time in Asia, however, I wrote absolutely nothing and instead just walked the streets of Seoul. That is how I met my wife. From that point on, my relationship with Korea becomes quite obvious. We got married in Colombia, lived a while in Spain before finally deciding to move back to Korea in 2013. Around that time, I started to write a book about my experience in Korea as a foreigner, Korea: Notes From the Tightrope, then the publisher received it and decided to publish it in Spanish in late 2014[1].

Annals: How do you believe Korea has changed you personally, and how has it influenced your career as a writer?

Solano: How Korea has changed me as a person is hard to see, and those changes are really only noticeable after a long time. Even though I am unsure as to how Korea influenced me on a personal level, I can say that the job I was offered in Korea at the Institute of Translation has given me enough free time to write, allowing me to advance my career as a writer. Before coming to Korea, I had only written one novel. The second was written between my stays in Colombia, Spain, and Korea. Besides these two works, all my books have been written here in Korea, which goes on to show how much my writing career has advanced since coming to Korea. If I had stayed in Colombia, I might not have had the time to write and would have just stuck to a full-time job as a journalist.

Annals: How is your relation to Korea and Korean culture as a foreign writer?

Solano: I have written three books and two short stories directly related to Korea. I think it is proof enough of how much Korea influenced my writing. Other than that, it is difficult to answer such a question and pinpoint such an abstract concept. What I can say for certain, however, is that I have fostered a great interest in Korean art and photography. I have worked with Korean artists Ram Han, Kyam Ah-Yeong, and Ku Dong-Hue for the Busan art biennale 2020, and I was asked to consult on Bogota, a Korean movie filming in Colombia at the moment.

Annals: Were there any Korean or East Asian influences in your life before coming to Korea?

Solano: When I was in university, I took a few classes on Japanese literature and culture, so most of my references began there. The majority of the works I read were written by Japanese writers. Once I came to Korea, I was immersed in Korean literature. These last few years, I have been captivated by Kim Seung-Ok, who wrote A Journey to Mujin, even though I am not sure to what extend he influenced my work.

Annals: Do you believe Colombian authors often have the opportunity to branch out internationally like you did, especially in Asia? What allowed you to branch out internationally and capture the Korean audience?

Solano: It depends on the desire or the need of each to branch out. What kickstarted my international career was being selected as one of the 25 best Spanish storytellers by Granta, a renowned British magazine. From there, my work got translated into multiple languages, and I caught the eye of Japanese audiences in Granta’s special magazine issue in Japanese. For the special edition of Granta Japan, I was tasked to write a story, and it occurred to me to write a story that dealt with both Korea and Japan. The story featured a Busan-born detective, the first non-Colombian character that I ever wrote, traveling back to Busan after growing up in Japan. The story traveled back to Korea, and I guess that is how it caught the public's attention here. I believe that was the push that made my work go international, yet all I had to show was my written novel, nothing else. In the end, what supports your work as a writer is your writing. It is not easy to plan for your work to go international, and I do not even know if it is possible to plan it. Other countries must have tools to help their authors branch out internationally, maybe scholarships or residences, but in Colombia, it does not happen very often; each is left to their own.

Annals: How are your writing, editing, and publishing processes here in Korea?

Solano: Publishing my novels in Korea is by no means easy. However, since a Colombian writer living in Seoul is so rare, it catches the publisher's attention. Plus, my wife is the one who translates the samples of my work we send to publishers, making the process slightly less difficult. For my editing process, something I learned since Korea: Notes From the Tightrope is to print and cut out the pages I write, then see the evolution of feelings, and start to reassemble the puzzle, thinking of a narrative and the dramatic arc.

Annals: It has been about four years since the Korean translation of Korea: Notes from a Tightrope was published, how is your relation with the book, and is there any differences between the original text and the translated version?

Solano: That novel was written under very special circumstances: it was my first year living in Seoul, and I was struggling financially. When it came time to do the Korean translation, I made a few adjustments not to bore the Korean audience. I always tried to keep a non-judgmental position in my works about Korea, no matter my situation. But plenty of adjustments for small details are made. For example, explanations on things that the Korean audience would be familiar with—such as what Kimchi is—were taken out. Even though my relationship with my Korean audience is limited, I understand they perceive the book with a tone that is different from its original version. I have been told that Korean translation, which my wife wrote, reads very naturally.

Annals: You mentioned that your wife translated your books—how involved were you in the Korean translation, and how you relate to the translated text?

Solano: The translation is entirely my wife's work; I do not know how the final product turns out exactly. Of course, living with me, I share a lot of my writing process with her, and she knows the books beforehand. She understands my story, intention, and my language. Our conversations translate into the books, and when she translates, she makes her own adjustments. In the end, it is more of a rewrite than a translation. Translators leave a lot of themselves behind in the text, and when Koreans tell me that they really like the book, I wonder how much of herself she left behind. I know the book is not entirely mine but also hers. The best thing to do, I learned, is to detach yourself from the book once it is out of your hand and not worry too much about the translation process.

Annals: How do you feel about the Korean's audience reactions to your writing? Conversely, how has your Colombian audience responded to your recent focus on Korea?

Solano: The novels are a mixture of my impressions of Korea and my personal life, my marriage, and there are a lot of details. Many Koreans, even those who knew me, were shocked by the degree of intimacy shared and portrayed in the book and how my wife not only allowed me to write about private matters but had also translated them. In reality, I was not too out there. I was simply portraying the ordinary life of two people who come from different cultural backgrounds and who live together. I expect that many others would have the same experiences when they are in an interracial relationship. I didn't say anything uncommon for married couples to go through, which is why I was surprised by the fact that the readers were taken aback by my inclusion of such details.

Korea: Notes From the Tightrope focuses on someone in a foreign land exploring marriage with a person from another culture. Many Colombians who have a similar story, without any relation to Korea, have seen their life reflected in the book, understood their own process of familiarizing themselves in different countries, and what it means to live with someone from another race or who speaks another language. It surprised me how well the tensions between interracial couples were reflected. The book has traveled places I never expected it to travel and read by people I never thought would read my story. For example, I was surprised to see that Anglo-Saxon readers also saw something in my writing that resonated with them.

Annals: How do you want your works to be remembered?

Solano: I do not know. I have never thought about it. Books will have their own paths later on. That kind of thing does not motivate me. I do not like to think about a reader, not because of arrogance but because if I do, I feel I would not be totally honest. I would mold my writing to try and satisfy an imaginary audience and would not be honest with the real reader.

Annals: You've mentioned in previous interviews that you were not planning to write about Korea anymore—what changed your mind for From Fever Days?

Solano: I always have intentions, like when I wanted to be a journalist only for one year but ended up working as one for ten years. Life never works out the way you plan it to. Right now, I find myself at a crossroads with my work. My intention is not necessarily to write about Korea, and yet something always crosses the way. For example, I did not plan to write From Fever Days because I did not have the time. However, it was impossible for me not to write about the pandemic. My intention for writing the book was to understand more about Korea and how the pandemic was shifting the tectonic plates of Korean society—mixing that with our day-to-day anxieties created From Fever Days. More recently, I was asked to write a story by an art curator of the biennial of Busan, and I decided to revive the character of the Korean Detective from my Granta Japan feature, the one that first allowed me to get known in Korea. Korea always ends up just knocking at my door.

Annals: You mentioned in a previous interview you were interested in writing a new genre, "ajuma noir." Are those plans still in motion?

Solano: Yes, that is another plot roaming in my head, featuring one of the Yakult ladies. I always see those ladies coming and going with their carts, and I started imaging a detective story surrounding them. While delivering yoghurt, they often visit Seniors who live alone. For many, those Yakult ladies are the only contact they have with the rest of the world. It is as if the Yakult ladies serve a sort of fascinating social security work. You end with a novel genre of "ajuma noir" by mixing a detective-like narrative with the world of the Yakult ladies.

Annals: Are there any other works you are interested in or have any new plans ahead? Are you planning to publish more of your works in Korean?

Solano: Before writing From Fever Days, I was working on writing about New York in the 1970s. I reconnected with the story a few months ago and I am working on it again, but I do not know whether I will finish that project. We are also trying to publish Neon Cemeteries in Korean. Neon Cemeteries is a story about a Colombian veteran who served in the Korean War returning to Seoul 50 years later. I believe its content may be of interest to certain readers in Korea, so hopefully, the third Korean book is on its way.

[1] The Korean translation was published in 2018.