Pleasure held hostage by violence

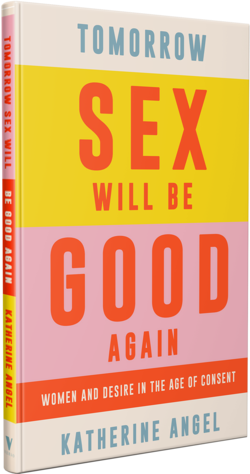

SEX IS complicated. It can be a beautiful experience of vulnerability and realization of one’s desires, but it can also be a woman’s source of anxiety, pain, and shame. How do we navigate sex to get the most mutual pleasure out of the experience? Katherine Angel’s book Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again: Women and Desire in the Age of Consent attempts to reveal the various social and cultural phenomena that obstruct women from having good sex. Surprisingly, Angel’s main point of critique falls on “consent culture,” which pressures women to state their desires with confidence. At first thought, consent is an obvious requirement for any sanctionable sexual interaction, but Angel urges readers to take a closer look at its limitations.

Consent culture: a foundation for bad sex?

Angel defines “consent culture” as the “widespread rhetoric claiming that consent is the locus for transforming the ills of our sexual culture.” #MeToo movement and progressive feminists posit consent as the main requirement to not only prevent sexual violence but also for good sex. However, as Angel points out, consent is simply a legal notion that is incongruous with how one actually experiences pleasure and desire. What if we are uncertain about if we want or do not want sex? The rhetoric of consent would say “No! Do not engage! You must be certain about your desires!” to safeguard women from potential sexual violence but, as a consequence, denies them sexual exploration. Effectively, “sexuality is held hostage to violence” and women are forced to accept subpar sex as an inevitable reality.

Consent does not consider the ambiguity and uncertainties that occur during sex. The expectation for women to voice their desire before sex assumes that women always know what they want, and can immediately make an informed, confident decision to engage in sex. However, Angel points out that desire for women is more “responsive” and often only emerges throughout interaction and context: “the build-up to seeing a partner after time apart […] or the giddy early stages of a new relationship.” Oftentimes, women’s desire for sex is mistakenly seen as always present. However, some women might not have sex immediately on their minds but could be open to the idea. In this case, she would experience arousal first, and then if met the right conditions and context, have the actual desire to have sex. In light of this, consent culture sets up women for bad sex in the way that it pressures them to actively communicate desires that they do not even have without considering the necessary steps to even incite those desires.

Unclear concept of consent

While Angel offers a strong argument on the limits of consent culture, she later states “asserting one’s boundaries […] may be important ground for the possibility of pleasure in the first place.” While this seems to be a point of contradiction in her argument, the important point that Angel emphasizes is the difference between knowing what you want before sex and knowing what you want during it. There should be no assumption that women confidently know their desires before sex, but an understanding that women’s desire emerges through interaction.

Then what is Angel’s perception of a viable form of consent? A major pitfall of the book is that this largely remained unclear, as her “solution” to bad sex was never clearly connected to the expansion of consent to accommodate ambiguity. The readers were left to connect the dots themselves. Part of her “solution” to bad sex is that the burden of sexual ethics should not be placed on consent but on “a conversation, mutual exploration, curiosity, [and] uncertainty.” However, isn’t a “conversation” basically another word for consent? After much contemplation, it seems like the crux of Angel’s argument is that consent should not be a black and white “yes” or “no,” but should be more ambiguous to allow space for uncertainties. “The fixation on yes and no doesn’t help us navigate these waters; it is precisely the uncertain, unclear space between yes and no that we need to learn to navigate,” Angel says. Consent, then, should not be a single affirmative or refusal, but a myriad of agreements and negotiations that do not always have to be verbal.

While I acknowledge that consent should accommodate a more explorative process, is there no room for prior agreements or planning? She states, “when I invite someone in—when I want them to enter—I can never be sure that they will enter in the way that I want them to. Nor do I always know in advance how I want them to enter.” But how do we even “invite” someone to engage in sex? Does any sort of planning risk bad and unexplorative sex? After I read Angel’s book for the first time, I was entranced by her argument. However, taking a closer look, the goals she suggested seemed difficult to attain in everyday life. For Angel, it seems that good sex is some miraculous and unexpected encounter that requires no initial planning, which I find to be unrealistic.

Good sex can only be rare?

Good sex, according to Angel, is a “rare” experience when partners attain mutual trust while negotiating the fear and risks involved in sex. To have good sex, we must be mutually vulnerable and constantly work out the “power imbalances between men and women [that occur] minute by minute, second by second.” However, Angel’s solution glosses over how easily trust in sex can be broken. Women may want to “let go” during sex and be fully vulnerable with their partner, but there is always the chance that her cry of “stop” or “it hurts” will not be acknowledged midway. Furthermore, Angel’s solution seems to disregard how our culture and society tend to place more value on men’s satisfaction during sex. Dr. Laura Mintz, the author of Becoming Cliterate, states how the “orgasm gap” comes from convoluted portrayals and understandings of female pleasure. Porn and mainstream media set penetrative sex as the standard, disregarding the need for clitoral stimulation. Therefore, it is rarely seen as problematic if a woman does not orgasm during sex, but it is seen as a given that a man should finish. Sex then becomes a chore, an obligation that women must tend to the sexual needs of their partner. Angel referenced research by Debby Herbenick, which found that when “women speak of ‘good sex’, they tend to mean the absence of pain, while men mean reaching orgasm.” In light of the grim reality of our society’s low standards of sex for women, it is no wonder that good sex is a rarity.

* * *

Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again: Women and Desire in the Age of Consent by Katherine Angel reveals the overarching social and cultural obstructions to achieving good sex, but her call for mutual vulnerability seems to be an unattainable dream. The sad reality is that women have to rely on consent to protect themselves from sexual violence. While Angel’s novel does not offer the end all be all solution to the complex issues barring women from good sex, she still gives invaluable points to make women think more critically about what is limiting their sexual exploration. If you have the chance, and you feel safe being vulnerable with your partner, take the risk and free yourself from the rigid boundaries of consent. It is okay to not always know what you desire; the joy of sex is exploring your desires and finding out what you want over and over.