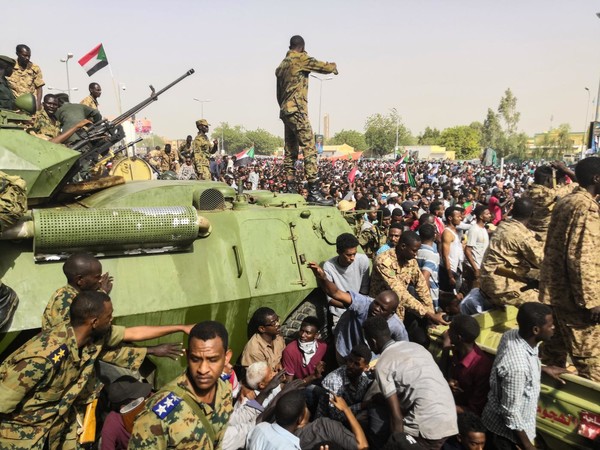

Sudanese civilians protest against the military government

SUDANESE CITIZENS are holding widespread demonstrations in opposition to the military rule initiated by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan’s coup d’état on Oct. 25, 2021. Prior to the coup, Sudan was in the process of transitioning towards a democracy after long-time ruler Omar al-Bashir was ousted in 2019. Al-Burhan’s coup and the subsequent military government have prevented the country’s transition to a shared civilian government. At least 85 people have died as of March this year due to repeated violent crackdowns on protests and demonstrations, inciting international concern[1].

The history behind the Sudanese government

Sudan has had a long history of military rule since 1969. Before the coup, Omar al-Bashir was the long-standing ruler of Sudan from 1993 to 2019 and only released his iron fist after the eruption of mass protests across the country. These demonstrations were initially sparked by the steep increase in the cost of living due to the country’s failing economy[2].

After weeks of protests and the eventual removal of al-Bashir in 2019, the Forces for Freedom and Change, an organization of civilian protestors, and the Transitional Military Council signed an agreement to transition towards a bipartite governing body[2]. This involved establishing the Sovereign Council with six civilians and five military members that would control the nation until the facilitation of a democratic election[3]. Abdalla Hamdok, an economist and well-regarded official of the United Nations (UN), was sworn in on Aug. 21, 2019 as prime minister of Sudan to oversee the transition process. Both the international society and Sudanese people looked to him to alleviate pressing issues such as economic instability, growing unemployment levels, and rising food prices exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic[4].

Despite its agreement to work towards a power-sharing structure, just two years after Hamdok was sworn into office, the military’s reluctance to forgo its power triggered a coup led by al-Burhan in October 2021. Hamdok was captured by the army under claims of a “growing political crisis…that could have led to civil war.”[2] Although Hamdok was reinstated a month later after signing a new power-sharing agreement, he ultimately resigned in early 2022 due to accusations that the agreement failed to curb the military's power. Subsequently, the military—and al-Burhan—regained full control of the government and did not honor the agreement to establish a shared-power government in Sudan.

Severe human rights violations

At Khartoum, the heart of the anti-coup protests, security forces opened fire on civilian protestors in 2021, leaving hundreds wounded and countless dead. The police have been accused of using live ammunition, rubber bullets, and tear gas in an attempt to crush the growing number of protests across multiple cities[1]. According to witnesses interviewed by the Human Rights Watch, there were no preemptive instructions ordering protestors to break up before teargas was fired at them from close proximity. Firing of chemical gas from a close distance violates UN human rights standards as it can induce severe injuries[3].

In addition to such heinous forms of violence, Sudanese authorities have begun clamping down on media freedom and arresting key activists of the insurgence. Ever since al-Burhan took control, numerous media offices have been attacked and live broadcasting of demonstrations have been banned[5]. In January this year, the Sudanese Ministry of Culture and Information removed Aljazeera Live’s broadcasting license and shut down their office in Khartoum[6]. Furthermore, activists involved in organizing the mass demonstrations have been arbitrarily detained without substantial charges. Khaled Omar Youssef and Wagdi Saleh, the spokesmen of Sudan’s primary civilian bloc, were arrested one day after they partook in the UN’s consultation initiative that was designed to mediate tensions[2].

The future of Sudan

The Sudanese government’s atrocious human rights violations have received worldwide condemnation. In 2021, the U.S. suspended $700 million in aid right after the coup took place, with Norway, Britain, and the EU threatening to cut off further economic aid unless civilians were actively included in the process of instating a new prime minister after the resignation of Hamdok[7]. In January this year, the European Union (EU) and multiple Western nations called for the discharge of activists, politicians, journalists, and other individuals who had been arrested arbitrarily[2]. As mentioned previously, the UN initiated consultations through the United Nations Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan in order to respond to growing tensions by having meetings with different domestic parties, completing their first round of consultations in February, 2022[7].

Some believe, however that the current international response is inadequate in sustaining long-term influence. Mohamad Osman, a researcher in the Human Rights Watch stated that “releasing detainees is the short-term goal” and that the international community should not ignore the “overall demands of the popular movement as they seek to establish the Sudan they want,” a Sudan with joint civilian rule. Moreover, in an interview with The Yonsei Annals, Park Jong-dae (Prof., Int. Studies) explained that “there have not been many cases where such international condemnations and sanctions have produced lasting positive outcomes in Africa,” arguing that international efforts can only have a limited impact on Sudan’s government. Yet, the halting of billions of dollars in aid has had a detrimental impact on Sudanese civilians, with a UN World Food Programme official estimating half of the population to be “facing acute hunger, double the estimate of last year.” The steeply rising prices of basic goods incited even larger protests across the nation in March, 2022[7]. International pressure is also able to affect internal, domestic factors that are vital to progressing the issue. Park revealed that Sudan’s military “may appear to be in control but its position is likely to be weakened over time.” The exacerbated economic situation due to the removal of international aid and the Sudanese civilians’ persistent opposition highlights the instability of the military regime. Moreover, the military faces a dilemma: if it agrees to share power with the democratic forces, it might be forced to take accountability for corruption and human rights abuses, adding another layer of complexity to the resolution of the core issue.

In the face of consistent violence, large scale pro-democracy movements have continued to grow. The Sudanese civilian committees met U.S. diplomats and officials from the UN in January this year, demonstrating their growing political power and capability. The Sudanese Professionals Association emphasized that they “will not leave the streets until the fall of the coup regime,” highlighting the protestors’ resilience. Some protestors have even gone as far as stating that they are “ready to die” for democracy[8]. Park states that the constant string of large-scale civilian protests signals the Sudanese citizens’ drive for “political and social change,” which neither the domestic political forces nor the international community can ignore.

* * *

The fate of Sudan depends on its citizens’ ability to sustain mass demonstrations throughout the nation. Additionally, the international community can support and invigorate civilians of developing countries like never before, through not only sanctions and aid but also through raising awareness on social media. The resilience of the Sudanese civilians and their strength, coupled with the international community’s response to the situation, signal hope for democracy.

[1] France24

[2] Aljazeera

[3] DW

[4] Forbes

[5] International Press Institute

[6] DaBang Sudan

[7] Reuters

[8] BBC