How fiction reflects reality

MILITARY FICTION goes hand in hand with the development of human history. Inspired by the historical events of war, military fiction had traditionally attempted to appeal to its audience by portraying exhilarating action and heroic tales. However, after experiencing multiple wars as a civilization, the concept of military fiction took a turn in its representation of war; instead of glorifying the deaths of soldiers, it began posing philosophical questions regarding the justification of violence and revealing the reality of what it really means to face death in combat.

The power of fiction

Fiction inevitably reflects reality—they are testimonies to the social atmosphere and sensibilities of a certain era. Thus, in terms of understanding human behavior, fiction is one of the leading authorities, asking the most important philosophical questions of the time period.

This is especially true when reading fiction that has been heavily influenced by major societal conflicts such as war. In military fiction, commonly referred to as “war novels,” the influential relationship between fiction and reality gives insight into how the subject of war was perceived by different time periods and cultures. For instance, in ancient Greece, the concept of a “war hero” was prominent in tales such as The Iliad, where themes like the gallantry of soldiers, glory of battle, and the honor of fighting to protect one’s country were highlighted throughout the plot. Such phenomena can be explained by the fact that military strength represented the amount of influence a nation had over its neighbors, therefore making military enlistment a priority. Early military fiction also portrayed the rather one-dimensional approach toward handling international conflict, revealing how the world’s population could simply be divided into those that should be protected and those that should be eliminated In the article “Functions of War Literature,” Catherine Savage Bosman defines this as the “heroic mode,” which refers to the psychological and social functions of military fiction. This refers to how the concept of war is closely linked with moral values such as honor and sacrifice, the identification of good and evil, as well as the male gender identity within small family groups.

Because of the reflective qualities of fiction, it can also be used in analyzing patterns of human behavior and collecting data in order to make meaningful conjectures. Project Cassandra, a research project aiming to predict future conflicts through the study of literature, attempted to do exactly that. Led by the German professor Dr. Jürgen Wertheimer, a team of literary researchers went through thousands of pieces of world literature trying to understand the relationship between literary content and real-life conflicts and made surprising discoveries. For instance, prior to the Kosovo war[1] between the Serbians and Albanians, there was a decline in novels depicting amicable relationships between the two ethnic groups. Revisionist historical novels such as Jovan Radulovic’s 1983 play Dove Hole[2] were also on the rise. Antagonistic tendencies in literary trends were found years before signs of military hostility. Despite being closed down in 2020, the accuracy of Project Cassandra was significant enough to provide intelligence for the German military in its foreign deployments.

The historical saga of military fiction

The literary atmosphere changed drastically after the first World War, which is one of the most traumatic incidents that overswept the world. The poet Wilfred Owen described the dark realities of war in works such as Dulce et Decorum Est. The title comes from the Latin phrase “Dulce et decorum est, pro patria mori” by the Roman poet Horae, which translates to: “It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country[3].” Owen criticized this notion by calling it “the Old Lie” that herds young men into their demise for an ambiguous cause.

Skepticism towards the justification of war correspondingly shifted the focal point of military fiction to the life of the individual outside the context of battle. Instead of having a character’s identity defined solely by their occupation as a soldier, novels such as Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms studied the life of the man underneath the uniform through a love story between the expatriate Henry and Catherine Barkley, the English nurse who lost her husband in the Battle of the Somme[4]. Military fiction also began to include narratives of civilian society and the destruction of personal life as a consequence of war. Such examples can be seen in Virginia Woolfe’s Mrs. Dalloway. The character Septimus is a World War I veteran suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who commits suicide as an alternative to being in a psychiatric ward; he represented many who still lived in the shadows of war. Clarissa, another main character of the novel, is suspected to suffer from depression, which she chose to ignore by trying obsessively to appear put-together in social situations. Woolfe, like many of the Modernist writers of the time, deviated from the “linear and deterministic[5]” style of Victorian writing and opted for a tone that is better suited to describing the devastation of World War I.

Through these changes, the definition of military fiction was broadened, assuming what Bosman refers to as the “imaginative mode.” As opposed to the heroic mode, the imaginative mode fills in the gaps between history by appealing “to readers’ imaginations through identification with characters and their emotions through literary language.” Consequently, factual narratives are supplemented with a personal interpretation as well as “experimental dimensions” that allow readers to explore the situation from different points of view.

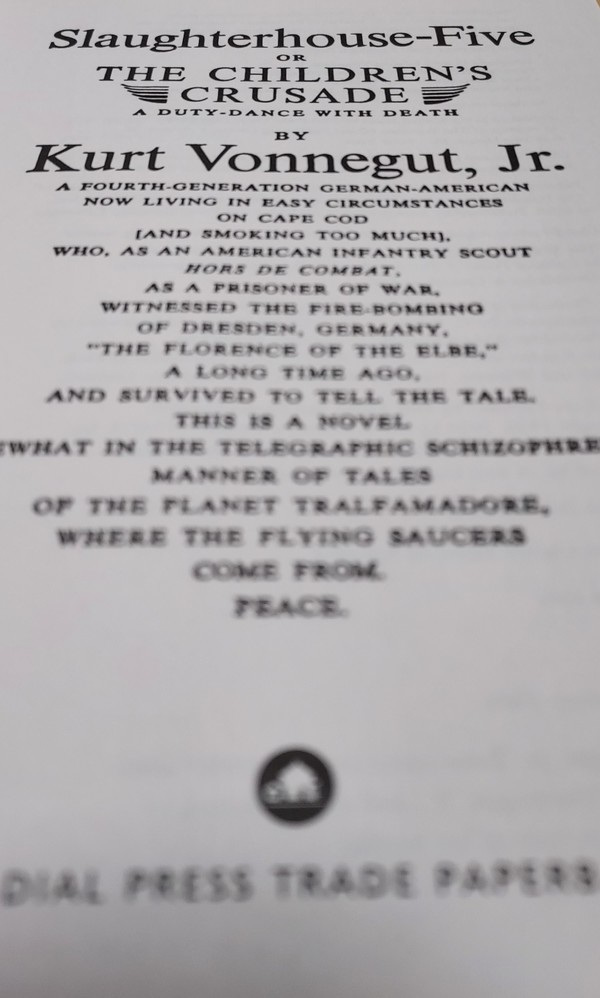

As the world’s power shifted from Great Britain to the United States, American fiction reached its “second flowering[6].” Norman Mailer, for example, adhered to realism when writing about the horrors of war in works like The Naked and the Dead. As one of the first novels to be released immediately after the war, the novel’s depictions of violence and hardship are still fresh on the page; flashbacks to each individual soldier working as complex layers building up to the tragedy. The shock of the nuclear bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki during the war rendered young writers pessimistic, dark-humored authors who wrote about the meaning of being human. Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut is one such example that accurately describes the reality of the Dresden Bombings through the eyes of the main character, who uses a detached voice to describe the realities around him. With the alternative title of the book being The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death, the novel understandably focuses on how an unremarkable young man is expected to fulfill the role of a hero in the state of war.

The importance of retelling

Decades after the two World Wars, writers keep coming back to the subject with a renewed perspective. So what are the appeals of military fiction? According to Paik Yoon-suk (Prof., Dept. of English Language & Lit.), curiosity would be one of the main reasons. “War has a pretty strong appeal precisely because it represents what we cannot experience in times of peace,” says Paik. He explains that the extremity of the situation presents a cathartic experience for readers that allows them to expand their imagination on how they themselves would have acted in the character’s place. “I think in the West there is an enduring interest in World War II,” he adds, “because it is seen as the source of most of the values that people in the West live by, such as fighting against tyranny or protecting the minority.”

Applying such a notion to the context of Korean history in particular, ethnic Koreans can attest that the Korean War is part of a foundation of values that we live by today, especially since the consequences of a divided country are still present. Despite the importance of this historical event, due to contemporary sensitivities surrounding the Korean War, films that deal with this topic often receive public scrutiny for being politically biased.

The unpopularity of the Korean War as a subject for military fiction is not limited to its home country. Some U.S. critics even named the Korean War “the forgotten war” because it is not actively produced as military fiction compared to similar historical events such as the Vietnam War. Paik explains this phenomenon by saying that it is “hard to fit the Korean War into a triumphal narrative. [From the American perspective], having divided the country between North and South, it didn't provide the United States with a clear victory.” It also did not have as much of a cultural impact on American society as other events such as the Vietnam War did. Paik continues that the Korean War happened in a time when the United States was “trying to return to a kind of peacetime economy, and focused on rebuilding people’s lives after spending years fighting in the Pacific,” which naturally reduced the production of military fiction.

The remarkable amount of information that novels possess can be traced to their method of production. In an interview with The Guardian, Dr. Wertheimer explained that writers have a “sensory talent” that allows them to detect cues in social phenomena, allowing them to “operate on a plane that is both objective and subjective, creating inventories of the emotional interiors of individual lives throughout history.” He also notes that literature is “an archive, storage for the collective experience of a culture, unspoken, revealing not only the state of mind but also the mentality of class, region and the place in great detail[7].” After observing the changing trends of military fiction, the ultimate question is this: do any of these novels help shape the perception of war for the better?

Taking a look at the recent invasion of Ukraine, it seems as if we are still living in the process of transformation. Sparked from the remnants of the Cold War, Russia’s pressure to keep Ukraine from being diplomatically familiar with the United States has reached a level of military violence. The fact that war is still a valid option to resolve conflicts between countries has caused international shock, as well as some anxiety of returning to a time of World Wars. Time magazine’s 2022 March issue titled The Return of History represents the globally shared sentiment.

Paik expresses surprise at how many people in the United States are calling for further military involvement against the invasion of Ukraine. He says that it is unclear how genuine the social media posts calling for action are, but he believes that this may be linked to the fact that American military fiction is almost always written from a perspective of a country that has never been “conquered.” “I would say that the best war literature is written from the perspective of people who lost,” he adds, saying that the experience of being conquered raises the most important questions in military fiction. “They are very conscious of what it means as a country to go to war and lose, and the kind of ramifications that defeat has, (. . .) and I think that's the defining experience of war.”

* * *

Often wars not only entail destruction and violence but can also prompt scientific or artistic development. The irony of military fiction is that great works of fiction are inspired by violence and mass destruction, which are then consumed in times of peace as cathartic relief. A want for chaos within order may be the uneasy relationship between war and civilization that is reflected in military fiction. Although military fiction might not have the power to presently stop all violence, it does indeed encourage the continuation of discourse about human behavior and the nature of war.

[1] Kosovo war: An armed conflict in Yugoslavia between the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Kosovo Albanian rebel group known as the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA)

[2] Dove Hole: A play about the Croatian fascist group Ustasha massacring a nearby village of Serbians

[3] Poetry Foundation

[4] Battle of the Somme: A battle fought between the British and French armies against the German Empire

[5] Britannica

[6] Malcolm Cowley

[7] University World News