Working for the District Attorney in New York

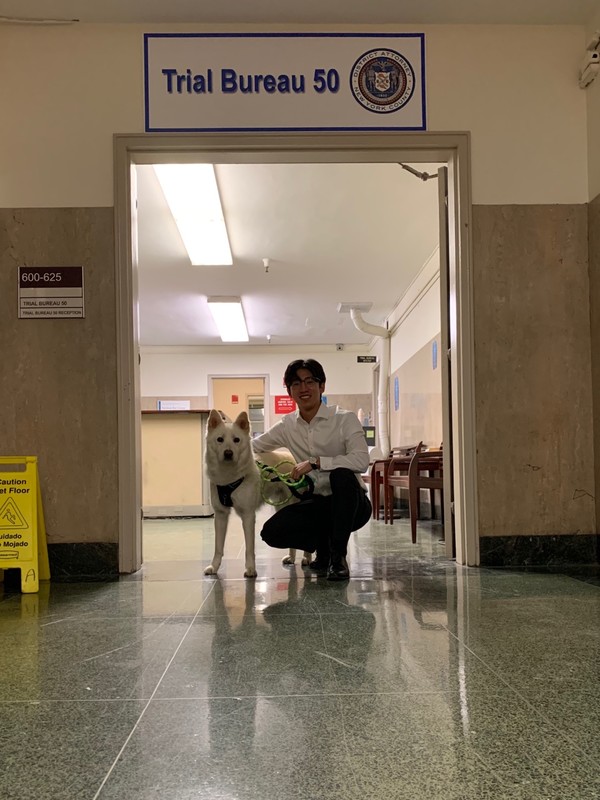

JONGSUK JEONG’s life choices are definitely that of someone who is not afraid to wander at the crossroads of different career options. In 2018, he graduated from Williams College with a bachelor’s degree in sociology. Then, he moved to New York City and worked at the Manhattan District Attorney’s (DA) office. At the time, he thought his work at the DA’s office would lead him to a career in law, so he worked there as an analyst for about a year and a half; after a while, he decided not to prepare for law school but to pursue a path into foreign affairs.

Annals: Can you talk about your work when you were an analyst for the Manhattan DA’s Office as well as the challenges you faced?

Jeong: I worked one-on-one with a prosecutor in all stages of investigation and trial. Most of the cases involved violent crimes including homicides, shootings, rape, and robberies. First, we have an arrest and then a grand jury. At the grand jury, we have to prove that the arrested person is reasonably guilty. If we are able to do so, we successfully get an indictment. Then, we go to trial if necessary. In many cases, there are plea bargains, especially for trials that extend over several years. I continued the cases that my predecessors worked on; likewise, my cases will be continued by future analysts.

As an analyst, my role was to provide investigative and trial support. Right after an arrest, in the investigative phase, we collect all of the relevant accessible information, including CCTV footage, hospital records, witnesses, and any other evidence that we can preserve. The investigative stage can sometimes continue until trial because we might need additional evidence to support our arguments and prove different elements that make up the committed crime. For the trial support, I had to liaise with a lot of different people and agencies to collect witnesses for the grand jury and trial stages. Witnesses can be anyone: civilians, police officers, correctional officers, doctors, the list goes on. We have to make sure the witnesses are well-protected and are present in the courtroom at the right time. This is not as easy as it may sound.

In South Korea, I sense a general respect people have towards the judicial system and their willingness to cooperate with prosecutors. In New York, however, people complain and generally do not want to be involved in cases as witnesses, which often presented challenges to my job. In fact, there have been many cases where witnesses have not shown up for grand jury or trial, even with police officers or doctors, who have been intimately involved with the cases since the arrests. Because police departments are overwhelmed with work, trial duty is not something they look forward to despite their obvious linkages with prosecutors. I usually had to negotiate with their bosses for their cooperation, and these conversations were often not the friendliest conversations.

Annals: Can you talk about specific violent crimes that you have prosecuted?

Jeong: I worked on the People v. Pinkston case, which was about a shooting in East Harlem. My prosecutor and I did not work on this at the initial stages of investigation and arrest, but we worked on it for trial. Essentially, the defendant showed up in a bodega, opened the door, and opened fire on the victim from a short distance away—it was a cold-blooded murder, where one just walks in, shoots, then simply walks out. Even though we had security footage of the defendant at the crime scene and of the actual shooting, we could not prove that it was indeed the defendant himself due to his facial covering.

This aspect posed an interesting challenge, requiring us to think of creative ways in which we could connect the defendant to the crime. The CCTV footage showed the defendant getting in a car and driving off after the shooting. We could track the car but still needed more solid evidence to conclusively identify him as the shooter. We also had a phone number that we thought belonged to the defendant. However, the problem was that the number did not have the subscriber’s information; the defendant was smart enough to not input his name when he signed up for the number. Thankfully, we found an application that the defendant filed to receive social benefits in the past on a separate occasion at the Human Resources Administration (HRA). He had written down his phone number on the application, and it matched the one we had.

Behind the scenes, I had to talk to HRA, get them to verify the information, and find someone to testify. Because of privacy laws, they were initially reluctant to release the information officially, so we had to explain that a judge could overrule the interest of privacy in the interest of justice. We became aware of this information at the last minute, so I had to work hard to get HRA to testify in time for trial. Eventually, we did get a conviction for this case, and the defendant was sentenced to prison for a long time.

Annals: What factors complicate the prosecution of violent criminals?

Jeong: One of the major challenges is, of course, the defense attorneys. In the justice system, everyone has the right to be defended, and there is always a chance that we might be pursuing the wrong person. Because of this, I cannot blame the defense for tenaciously defending their clients. Having said that, I think there is a mutual suspicion that each side is intentionally trying to make the other side’s job more difficult in bad faith. For example, per the law, we have to turn over all of the paperwork we have to the defense team. Some of the paperwork for the Pinkston case that we had to turn over to the defense was written in a smaller font size. This had nothing to do with us; we did not purposefully make the font smaller, but the defense lawyers still repeatedly demanded that we resubmit the paperwork with larger fonts because they thought we had done it out of spite. Instances like this, while somewhat humorous, were quite time-consuming and distracting.

Annals: How do people react when they find out that you worked at the DA’s Office?

Jeong: When people find out that I worked at the DA’s Office, it definitely gets their attention. I benefited from this aspect because employers usually want to hear stories about my cases. I also think they understand the complexity of prosecution work and appreciate the transferable skills I gained there. Like I mentioned before, communicating with a wide variety of people and getting them to testify in court is extremely difficult. Handling all these emotionally taxing tasks helped develop me into a person with excellent interpersonal skills. Another thing is that the cases I prosecuted had real-life ramifications, which meant that errors, however trivial, were not tolerated. As such, a great amount of scrutiny to detail is required—a skill I cultivated as an analyst at the DA’s Office.

Annals: What advice would you give to students who express an interest in working for the DA’s Office?

Jeong: My advice would be that students should put themselves out there for different kinds of experiences. For some time, I did want to be a lawyer, which is why I worked for the DA. While the experience was substantial and taught me various skills, it was not the career I truly wanted. If I had never worked for the DA, I would not have discovered my passion for foreign affairs and ended up as an intern at the State Department. Students have to try different things to know what career path they want to take, and they will never know which one suits them unless they actually give it a shot.