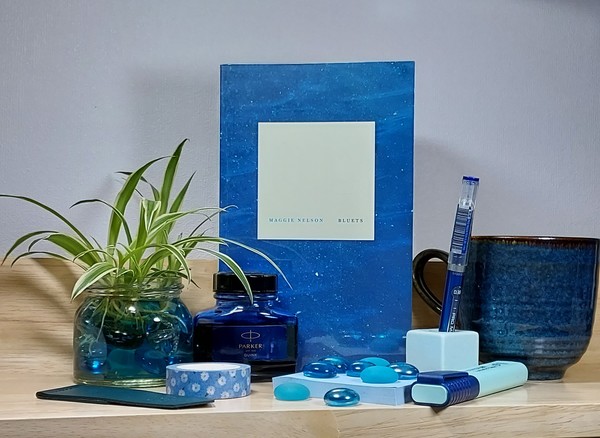

Seeing blue through the eyes of love

BLUE IS often regarded as the color of tranquility, intelligence, and freedom. It can be connected to the divinity of the blue sky, or the sign of global peace on the United Nations flag. At times it is a color of melancholy or even solitude. The enticing nature of the color blue to many people around the world suggests that it has a story to tell—a notion that author Maggie Nelson explores in her book Bluets.

Thinking in colors

It is difficult to say at first glance what type of book Bluets is supposed to be. The best way to describe the piece would be that it is a fragmented recollection of “blue” and everything it represents. When Nelson begins the book by saying that she has “fallen in love with a color,” Nelson’s blue seems to be the same as everyone else’s—the color of sadness—as she describes the sensation as “falling under a spell, a spell I fought to stay under and get out from under in turns.” The sadness Nelson experiences is due to her cutting ties with an ex-lover and taking care of a friend who was left paralyzed from an accident. Nelson writes that collecting blue objects distracts her from her depression and that it is her way of making her “life feel ‘in progress’ rather than a sleeve of ash falling off a lit cigarette.” Despite the generic association between the color blue and depression, it is interesting how Nelson claims that she is in “love” with blue rather than being subject to its negative influence.

Bluets is uniquely structured with 240 numbered paragraphs. Yet in order to accurately capture what blue means to Nelson, the paragraphs are unorganized and resemble the way thoughts flow spontaneously. According to Jocelyn Parr, a literary critic and writer, this format is inspired by the works of the early 20th century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who numbered his “propositions,” or mini-arguments, but made it so that adjacent propositions would contradict each other[1]. By doing so, he aimed to provide an intimate reading experience where the reader can see the writer’s raw thought process. Bluets takes this form of intimate reading a step further by directly addressing the reader as “you.” However, as the reader ventures further into the book, it soon becomes clear that the “you” Nelson is addressing is someone specific: the person she used to love. It is the realization that this book is addressed to the “prince of blue,” who betrayed and left Nelson, that puts her fragmented pieces of thought in a comprehensive order.

Once the reader reaches the conclusion that all the intricate descriptions of feeling, speculative suggestions of random facts, and quotations of philosophers boil down to something as trivial as “break-up poetry,” it is possible that there will be some disappointment. Nevertheless, the mix of scholarly elements and everyday dialogue is precisely what Nelson intended for Bluets. According to the Poetry Foundation, Nelson subscribes to the idea of “vernacular scholarship,” a term used by the poet Eileen Myles to refer to the “combination of the [everyday] conversation and the academic[2].” For example, there are multiple occasions where the speaker’s quotidian experiences of emerging from a rattled relationship are compared to different historical or philosophical references, such as the stories of Saint Lucy and other devout Christian women who clawed their eyes out in order to maintain their chastity. Nelson uses references like these to connect the shame that follows women’s sexual desires to her shame of wanting someone who does not want her back. As Nelson dwells more on her feelings, she begins to understand color as “visible emotion.” What she is feeling at the moment—loss, shame, and the pain of unrequited love—is translated to being in love with the color blue.

The many faces of blue

Just as a color is nothing but reflected light that appears differently from different angles, each numbered paragraph in Bluets can be conjoined or separated from different perspectives to form various interpretations. Whereas most readers would expect a book about blue to be a meditative reflection on sorrow or transcendence, approaching Nelson’s writing from such a place would only allow one to examine an incomplete version of blue’s true identity. Although the book does confirm the common perception that blue is associated with sorrow and heartbreak, it also discovers that what blue symbolizes is on a spectrum ranging from good to evil. This is inspired by the color blue’s actual historical perception as Nelson writes about how the meaning of blue changed over time. For instance, blue was not always a sign of order and divinity, because historically speaking, indigo blue was considered the color of evil and referred to as “the devil’s dye.” It was not until the 12th century, with the discovery of the color ultramarine, that blue was regarded as a holy color.

The contradictory nature of blue is present in Nelson’s own narrative. Blue, as in her ex-lover the “prince of blue,” is something that causes her pain, yet she finds herself seeking consolation in things that are related to blue. In the midst of the purity that blue represents, she finds a sort of hedonistic joy in collecting blue objects—possibly because they remind her of her ex-lover—and admits that being drenched in sorrow (blue) can be a form of comfort itself. She also connects sensual distractions such as drinking and sex with the color blue by pointing out that in certain cultures, “being blue” is closely associated with being drunk, as well as commenting on Andy Warhol’s erotic film Blue Movie. After exploring what she wants her “blue” to be—divine, tranquil clearity—instead of the hedonistic joy her “blue” is prone towards, Nelson admits that there is a shame that creeps in due to the disparity between her ideals and her actual reality. Although this initially is a source of distress, Nelson is of the opinion that her “blue” does not define her as a person. As she observes how sunlight bleaches her collection of blue objects, she concludes that blue, and all that it could mean, is impermanent and that her negative emotions—like the color blue in sunlight—will fade away.

Everyone’s blue and the blue of one’s own

The fluctuating nature of blue is perhaps best described by the fact that the perception of color itself is associated with “false consciousness.” Nelson acknowledges that color is not a “constant” that everyone perceives in the same way. Consequently, it is uncertain whether a color exists in the absence of observation. “Is your blue sofa still blue when you stumble past it on your way to the kitchen for a water in the middle of the night; is it still blue if you don’t get up, and no one enters the room to see it?” With this question, Nelson points out that emotions—much like colors—are fickle and uncertain in nature and it is sometimes misleading to ponder endlessly on one’s emotions because one cannot be certain that they are real. This is the conclusion Nelson comes to as she calls blue “pharmakon.” Pharmakon, the Greek word for “poison” and “remedy,” does not make a distinction between the two. Just as Plato claimed all colors to be pharmakon, Nelson is doing the same with her definition of blue as an emotion: that it is a phenomenon of both pain and beauty with no distinction between them, and that it has no agenda other than to exist.

* * *

Bluets can be interpreted as an attempt on Nelson’s part to understand the “blue” inside her. Even if the book can be dryly broken down in “a state of clinical detachment” by interpreting metaphors according to their traditional meanings, it can also be read as if the reader is communicating heart to heart with the author, drinking in her thoughts through her words. Bluets is a book that unravels the curious relationship between the self and the world, where all humans are shards of glass reflecting sunlight from their own angles.

[1] Brick

[2] Sub Rosa