The power of stories and human relationships

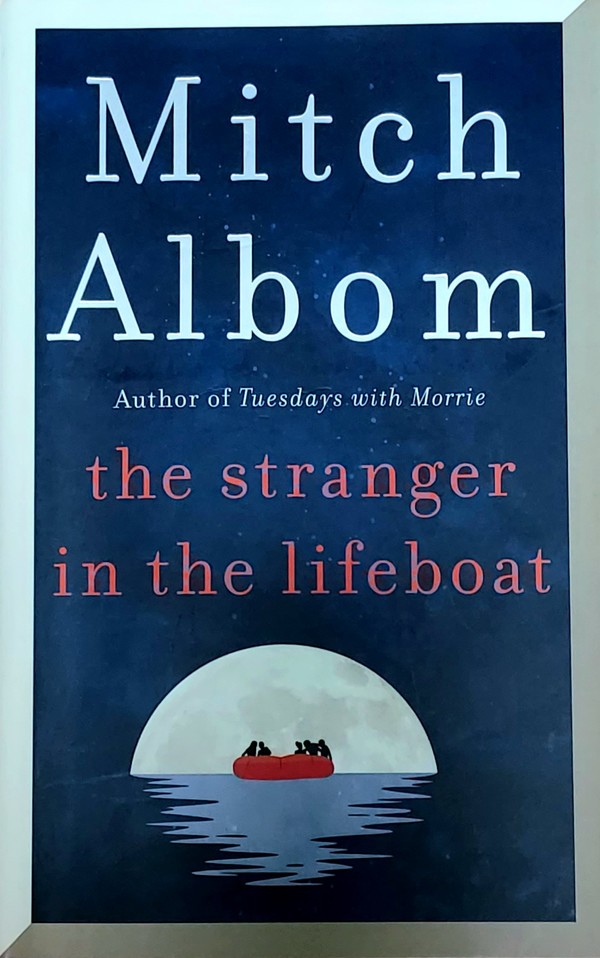

HAVE YOU ever wondered what it would be like to have God appear before you in a time of dire need? In his book, The Stranger in the Lifeboat, Mitch Albom presents an answer to this question. Following his candid and straightforward writing style, Albom describes how ten people stranded in a lifeboat navigate a life-and-death situation by relying on and looking after each other…all in the presence of a man who claims to be the “Lord.” In the midst of this surreal experience, Albom’s characters learn to believe their own capability to change the lives of others through the power of stories.

Benji and his notebook

The Stranger on the Lifeboat is divided into three alternating narratives. The first story is narrated by Benji, one of the people stranded on the lifeboat, who writes in his notebook about the incidents that occur in the sea. Among the three narratives, Benji’s story is the one that reads most personally, as he describes in great detail his efforts of survival and illustrates the heartfelt connections that form between each character on the lifeboat. Everyone on the boat had been significant figures in society as the voyage was supposed to be a networking party for “people who can change the world.” However, in Benji’s notebook, they are mostly described as ordinary men and women who—despite their prestige and distinction in society—are not unlike every other human being. Indeed, out at sea where the blue water stretches on as far as the eye can see, it is almost as if the survivors are on an entirely separate plane of existence, where all social status and accomplishments are rendered meaningless. Despite losing everything, the direness of their situation, ironically, brings out the good in the passengers aboard the lifeboat, as revealed by their extraordinary deeds of sacrifice and strength which form a genuine bond between the survivors—the kind of bonds that, considering each of their social status, would not have formed if they had met under normal circumstances.

In contrast to the compassion that the survivors show each other, the man who claims to be the Lord—despite his “reputation” as the savior of humankind—is strangely distant. In fact, when one of the passengers dies of an injury, he does not respond sympathetically as one would expect, but rather showers the remaining survivors with questions such as “Did he love others? Did he tend to the poor? Was he humble in his actions? Did he love me?” Behavior such as these contrast greatly with what we often naively expect God to be like. Yet, acknowledging the indifference of the Lord and the absence of a “Messiah” to magically save them from their plight seem to further unite the people in their desire to come out of this situation alive, strengthening their belief that they must rely on each other in order to survive. Thus, contrary to the expectation that the Lord is the “emotional rock” on which people should lean on during hard times, Benji’s story shows that the ways of God are too abstract and distant for men to do so. Albom, in the end, reveals that it was not the presence of a spiritual being that kept Benji alive, but rather the acts of the people that sustained his will to survive.

“Someone has to know!”

Benji also repeatedly states that he writes about what happened in the lifeboat because he feels there is importance in the act of “telling.” Upon the death of several people on the lifeboat, Benji writes as if to preserve their lives in the form of words and stories rather than letting their existence be forgotten and lost forever. Luckily, about a year later, the empty lifeboat and the notebook get washed up on shore and are found by a police officer named “LeFleur.”

By feeling the need to write, Benji unknowingly reveals the function of telling a story, which is beyond confirming whether or not something really happened. In Shakespeare’s 55th sonnet, there is a line that says “Not marble nor the gilded monuments/ Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme,/ But you shall shine more bright in these contents/ Than unswept stone besmeared with sluttish time[1].” This praises the immortality of literature, and how a person may withstand time if a story about them is left behind to be told to many others over generations. Likewise, when LeFleur discovers the notebook and reads about the individuals who had been in the now-empty lifeboat, each survivor is given a new life within LeFleur’s memory.

LeFleur, being the observer of Benji's Story, has already seen the news reports about the famous shipwreck of the yacht that held a group of successful people. The news report, which profiles everyone on the lifeboat by describing each of their life’s work and how they became a significant figure in society, thus becomes the third narrative that is woven between stories illustrated by Benji’s writing and LeFleur’s point-of-view, adding further information about the context. Some, like Mrs. Laghari, had started from poverty and worked her way up, some were ambassadors of foriegn countries, and some, like Lambert, became rich by playing the game of capitalism. Although these descriptions allow the readers to get a better understanding of each character, the news story alone cannot evoke any sort of fondness towards the survivors as it is based on hard, dry facts; LeFleur, reading through the notebook, recognizes these names from the news, but it is only after he has read a significant amount of Benji’s story that he begins to connect to them on a personal level.

Although the unrealistic presence of the “Lord” and the little “miracles”he performs—such as making it rain for a couple of hours or waking up an unconscious woman—makes it hard for LeFleur to take Benji’s records as facts, he slowly allows himself to believe in the existence of the ten survivors who showed humanly kindness for each other in a time of crisis. Without LeFleur’s narrative, this book would have simply been a modern Bible story about the importance of believing in God. However, LeFleur puts the story on the lifeboat in perspective by showing the audience how he heals his own emotional wound through the process of interacting with a story that—regardless of whether it actually happened—brings value to its readers. Instead of giving LeFleur religious guidance on whether or not God exists, the notebook provides a “possibility” of divine intervention that can be found within the kindness of people. In doing so, it is revealed how the true God resides in each of the individuals on the lifeboat, not as an unknown, foreign “stranger.” It can thus be concluded that the illustration of human strength through the medium of stories, as well as the human ability to inspire others through it, are what enable a ripple of change throughout the human race.

* * *

The Stranger in the Lifeboat is a book about the power of human relationships illustrated by the influential power of telling stories. It is enlightening to see how inspiring human relationships—immortalized through stories—can fill one’s empty life with hope. Albom explains that“We’re all in a lifeboat getting by with what we do and there is a force with us. If you believe in nothing, and have no hope, the force is always going to be a stranger[2]”—the“force” mentioned here refers to the power of stories, the one saving miracle that mankind have shared since time immemorial.

[1] Poetry Foundation

[2] Dove.org