The cost of being normal

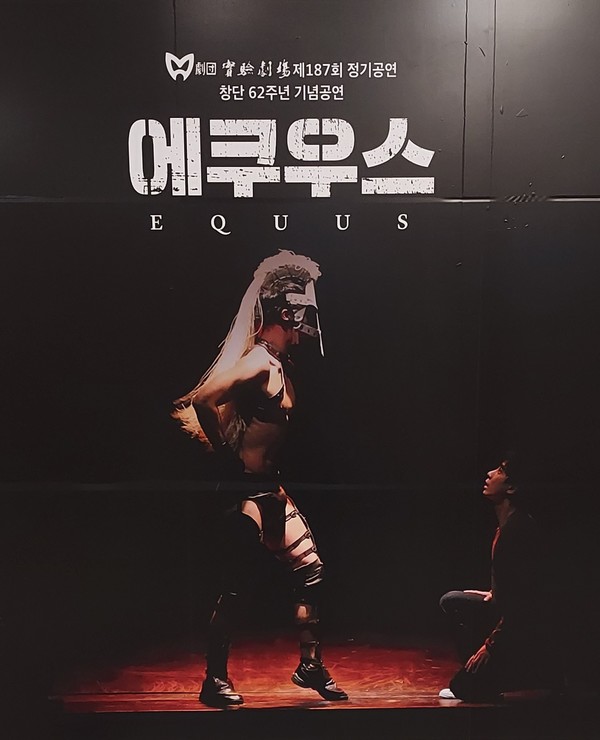

SHAPED LIKE a stable, a square stage greets the audience as they file into the theater. A pale blue light encompasses the area with an ominous glow, and the minimal set design with the prop of two simple stools that promise potential. Sure enough, the tiny space is all it takes to transfer the audience into Alan Strang’s various memories. He is a teenage boy who is admitted as a patient at a psychiatric hospital for stabbing the eyes of six horses in a frenzy. The play unfolds a harrowing but beautiful tale of a boy who allowed himself to be consumed by the extremities of divine passion.

The story of a boy who killed his god

Equus is a Tony award-winning play written by Peter Shaffer, a British poet known for other works such as Amadeus[1] and Lettice and Lovage[2]. Inspired by a real-life incident where a 17-year-old boy was accused of blinding six horses in Suffolk, Shaffer wrote the play by imagining the motive behind the crime. Thus, Equus is an intense play that portrays Alan’s raw emotional expression in the midst of passionate turmoil, as well as his maddening attempt to contain it.

Beginning with a monologue, psychiatrist Martin Dysart recounts his interactions with Alan Strang, who is called in for stabbing six horses in the eye. Marin speaks directly to the audience as if looking for someone to agree with what he is saying. This continues throughout the play in between portrayals of Alan’s memories, with Martin’s commentary helping the audience navigate through the story of the boy’s unusual interactions with horses. As more is revealed about Alan, the play begins to show his relationship with his parents.

Alan’s mother, formerly a schoolteacher, is a religiously devout woman. In fact, every day since Alan was a young boy, she had read the Bible to him—an act that was disapproved of by his non-believing father. His father thought it was inappropriate for a young boy to be hearing about “violent crucifixions.” His atheist tendencies were also associated with holding a stoically negative view of things that make a person’s mind not his own, such as the mindless indulgence of the television. Both of his parents have what is considered a “normal” response to the concept of spiritual power: to either blindly believe in it without fully understanding what it means, or to distrust it completely. Alan secretly finds this suffocating, as his religious zeal is more complex and therefore cannot be categorized into either of those tendencies.

Alan recalls his first encounter with horses when he was six years old. He remembers how the horse’s eyes mesmerized him and brought out powerful feelings that he has never felt before. Yet his desire for horses was different from the equestrian intention to ride them. “Bowler hats and jodhpurs!” he complains. “To put a bowler on it is filthy! Putting them [horses] through their paces![3]” This, along with his aversions to whips and spurs that are used upon the horses, indicates that Alan sees them as something other than creatures that are bred purely for human leisure activities. He describes in detail the beauty of their eyes, their skin, and the way beads of sweat travel down their necks, almost as if he is speaking of a loved one. It is no surprise, then, that his favorite biblical story is also of a horse that does not permit anyone to ride it other than its owner, the prince. The nature of Alan’s curious passion is revealed when Martin hypnotizes him to confess what he was doing with the horses when he worked as a stable boy. As Alan begins to speak, the stage transforms into a reenactment of his memory depicting how he rides a horse named Nugget—whom he calls Equus—in the night, bareback and naked, imagining himself as a king who has become one with his equine god. His relationship with the horses is an amalgamation of sexual and religious devotion, as well as an indication of his desire to harness a divine power by becoming one with Equus himself.

With a better understanding of Alan’s psychology, Martin coaxes out of him the details of what happened the night he stabbed the horses’ eyes in the stable. He was out with Jill Mason, a coworker from the stable Alan works in, who convinced him to see an adult film with her at the theater. In the theater, however, they run into Alan’s father. Upon the sight of his uptight father secretly seeking pleasures, Alan realizes the hypocrisy of society where everyone pretends to have nothing to do with unruly things, such as passion or desire, but covertly tries to fill the emptiness left by unmet needs. Shocked and disoriented, Alan follows Jill into the stable where she tries to seduce him into a sexual interaction. However, Alan is deeply paranoid by the hallucinations of the horses’ eyes that portray anger and jealousy, judging him for devoting himself to another in the very shrine of his god. Unable to withstand their condemning gaze, Alan begins to stab the horses’ eyes. It is undoubtedly the most heartbreaking scene throughout the entire play; a massacre of the gods by the hands of their worshiper who failed to carry the burdens of his zealous devotion.

A murderous priest

Martin becomes progressively more distressed as Alan continues to talk about his relationship with the horses. Earlier in the play when he decides to take Alan as his patient, Martin tells the audience of a dream where he was one of the priests of an ancient civilization, charged with the task of sacrificing children by cutting their intestines out. He says that with every child he sacrificed he felt more and more nauseous of his behavior, yet he had to carry on for fear that the other priests standing by would notice his discomfort. For if it was known that he had an aversion to his work, the others would put him on the altar instead. Martin’s career, being a child psychiatrist, has consisted of making children “normal” with his treatments, but he is at a point in his life where he feels as if he is performing the work of the priest within his dream, maiming young children and murdering their individuality for the sake of making them acceptable in the eyes of society. The distress Martin feels during his encounter with Alan is not caused by his fear of Alan’s behaviors, but rather by the beauty that he sees within the nature of Alan’s devotion. Martin laments at the fact that making Alan “normal” would mean that he would have to remove the pure and creative passion that the boy possesses.

Just like all the adults in the play, Martin also has an emptiness caused by unfulfilled desire. He is introduced as a romantic man fascinated by the primitive power of ancient art who often spends his evenings reading books about the ancient Greeks. Yet, Martin is married to a woman who is disinterested in both him and his interests. As the play progresses, an interesting dynamic develops between the psychiatrist and his patient where it looks as if Martin is trying to live through Alan’s experiences and wishes to be part of the boy’s blinding passion that he himself is no longer capable of possessing—“But that boy has known a passion more ferocious than I have felt in any second of my life. And let me tell you something: I envy it[3].” This dynamic is accentuated by the fact that, whenever Alan takes the stage to reenact his memories, Martin does not retire to the side, but remains a part of the scene by sitting and watching from a distance, occasionally commenting on what he is seeing. As the time comes to diagnose and cure Alan of his abnormal behaviors, it almost seems as if Martin is disheartened that their interaction is coming to an end, just as an audience might feel at the end of a particularly engaging play.

* * *

“I’ll erase the welts cut into his mind by flying manes. When that is done, I’ll set him on a nice mini-scooter and send him puttering off into the Normal world where animals are treated properly: made extinct, or put into servitude, or tethered all their lives in dim light, just to feed it![3]” These are the words of Martin as he ends the play with a monologue, criticizing how civilization harnesses an explosive power of pure and primitive passion with bridles, whips, and spurs to make them “normal.” The horses, symbolic of wild spirits, are conquered and manipulated by civilization to perform tasks that are required of them. Despite the fact that the play ends with a return to normal, the experience of the passionate storm stays with the audience as they exit the theater.

[1] Amadeus: A play about the musical rivalry between Mozart and Salieri

[2] Lettice and Lovage: A comedic play about an English tour guide who likes to embellish the history behind an old cottage for his visitors

[3] Equus