A conscious meditation on the mundane in films and novels

AN ENIGMATIC profundity—at once enlightening and familiar—exists within the mundane nature of films and novels where nothing much happens. In fact, such pieces are devoid of dramatic moments and lack a visible climax; even if there was a story arc, its slopes are ever-so-slight and the narrative components so negligibly quotidian that whatever remains of it blends into the background static. However, it is precisely the mundanity of it all that provides the profoundest insight into the essence of humanity, capturing them in all their raw, undecorated beauty.

Plotless mundanity of the “slice-of-life” genre

Generally speaking, slice-of-life genre refers to visual or literary works that attempt to capture seemingly mundane and quotidian “slices,” or moments, from one’s life[1]. Scenes from such pieces may appear as though they lack a clear purpose, not because they were designed poorly, but because emphasis is placed on individual moments rather than the magnitude of its contribution to the overall narrative. Unlike most mainstream works, slice-of-life cinema and literature such as Lady Bird, The Florida Project, and Bell Jar tend to be detail/character-driven than plot/premise-driven.

Oftentimes, narrative techniques used in the slice-of-life genre do not follow traditional plot development in the sense that storytelling elements such as exposition, confrontation, and resolution are either largely absent or extremely subtle, making the films or novels feel plotless[2]. Terence Murphy (Prof., Dept. of English Language & Lit.), however, states that the pieces we often label as “plotless” are not genuinely without plot, but merely appears as such because they deal with the achievement of very basic and minor goals. Murphy explains that plot can be defined as a “succession of different functions by which a character achieves a difficult task,” or a “connected series of actions designed to lead from good fortune to bad fortune, and vice versa,” meaning that traditional plots usually have visible progressions of events which end with a clear denouement of sorts. In this sense, slice-of-life films and novels—which revolve around mundane events, feature ordinary characters, and lack a satisfactory resolution of remarkable conflicts—may appear to many as being plotless and monotonous.

Despite the unorthodox approach, however, mundane subject matters and seemingly plotless narratives provide a genuine depiction of reality. With no major plot points to distract the audience, elements that would normally be considered “secondary” rises to the surface: subtle emotions are magnified, truths that were hidden in plain sight reveal themselves, and everyday occurrences come to be viewed through a newfound perspective. In understanding ordinary characters, who, in many ways, are much like us, we gain a new understanding of human experience in its most authentic form, untainted by hypothetical or imaginary scenarios. In understanding their achievement of ordinary goals, which may be basic and minor, we come to realize the subtle magnitude of the struggles, losses, and victories we so often neglect in our pursuit of “bigger” conquests. Meditating on such aspects of the slice-of-life genre offers its audience the chance to discover beauty within the universal mundane, and to find profundity in the ordinary.

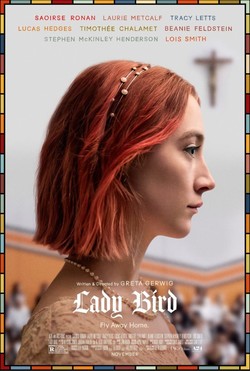

Familiarity in the mundane: an examination of Lady Bird

Directed by Greta Gerwig, Lady Bird provides a deliciously raw and honest portrayal of love between a teenage daughter and her mother. Lady Bird is a coming-of-age story about a 17-year-old Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson, who finds herself on the cusp of adulthood and struggles to navigate through the final moments of her high school life in Sacramento, California. Lady Bird, like so many of us at the green age of 17, dreams of escaping from the drab reality of her hometown to a prestigious—and expensive—college in the East Coast, “where culture is[3].” An ever-present conflict exists between her and her mother, Marion, as Lady Bird’s ambitions are limited by her working-class family’s financial circumstances. Gerwig makes the brilliant choice of portraying the puzzling nature of their love through their conflicts.

Despite the mundane and trivial nature of their fights, what makes Lady Bird and Marion’s love-conflict dynamic so profound is the familiarity that stems from its universality. Interestingly, Lady Bird and Marion’s disputes are characterized not only by their pettiness, but also by the mercurial state of their quarrels—one minute the two are arguing with burning hatred, and the next they return to their loving selves as if nothing happened. The nature of their relationship is most clearly shown in the scene where Lady Bird complains to her boyfriend, Danny, about her mother “always [being] mad” at her, but immediately defends Marion against Danny’s criticisms by saying, “Yeah, well, she loves me a lot[3].” These constant oscillations reveal a universal truth about mothers and daughters: that despite their conflicts, they are always able to return to each other’s arms—all because their relationship is firmly based on the unwavering faith in the love they have for each other.

Although Gerwig’s film is a plotless collection of mundane snapshots from a teenager’s life, the ordinary ambitions of Lady Bird, the triviality of her conflicts with Marion, and the familiar fluctuations of a mother-daughter relationship are what give the film its incredibly realistic and relatable quality. Such aspects would not have had the chance to be examined with such care in, say, mainstream Hollywood films, as the difficulties that Lady Bird face are far too quotidian to be worth covering in movies with contexts as grand as a blockbuster. However, the slow pace of the film, as well as its focus on capturing the authentically random and mundane moments in Lady Bird’s life, are precisely what provide the necessary stage for Gerwig to present on screen the familiar nostalgia of a bittersweet teenagerhood many of us had gone through ourselves.

Indeed, Lady Bird’s mundanity is profound because it mirrors that of our own.

Blissful ignorance within the mundane: an examination of The Florida Project

Sean Baker's The Florida Project depicts the everyday lives of a homeless single mother, Halley, and her mischievous daughter, Moonee. The interesting irony presented in this film reveals itself in the stark juxtaposition between the glistening fantasy of Walt Disney World, and the grim realities faced by the homeless population that live in motels just outside of “The Happiest Place On Earth.” The role that the element of mundanity plays in The Florida Project can be looked at in two ways: from the perspective of Moonee or the perspective of Halley.

When viewed in relation to 6-year-old Moonee, the quotidian subject matters of her scenes communicate the concept of childhood obliviousness toward the harshness of reality, as Moonee’s focus is not on the objectively significant crisis that her family is placed in, but is instead focused on the trivial and insignificant aspects of her everyday life—such as getting a free ice-cream or exploring an abandoned house—as most children of her age are. In other words, the mundanity of Moonee’s scenes illustrates the unworldliness of children which allows them to devote importance to the mundane over the objectively significant. Interestingly enough, even though many of the us have not led similar lives as Moonee, the film still resonates with us not necessarily because we feel pity for Moonee’s situation, but because we stare at the cruelty of our own reality and, in a strange and bittersweet way, admire the blissfully ignorant naivete of a 6-year-old girl—however reckless it may be. It is only because we lament for our adulthood that we are able to appreciate the beauty within the untroubled simplicity of Moonee’s world.

Halley is a parent that wants to be a child—the mundanity of Halley’s scenes, then, echoes that of Moonee’s scenes in illustrating her desire to be oblivious and irresponsible like her young daughter. This is most clearly shown when Halley, with the cash she receives in exchange for stolen Disney World passes, goes on a frenzied shopping-spree with Moonee at the dollar store; despite Halley being the parent and Moonee being her 6-year-old daughter, they both show the same childish frivolity. Moonee’s excitement translates to a bittersweet gaiety of an innocent girl who—in her young age—fails to understand her situation, whereas the sight of Halley excitedly throwing trinkets into her cart and galloping around with a pair of costume angel wings paint a telling picture of her immature indifference toward her grim reality as a homeless single mother. Such is also emphasized through the succession of insipid and idle days in Halley’s life, as well as her lack of proactivity and motivation. In other words, the reason why Halley’s scenes appear so quotidian and monotonously mundane is because there is an absence of “struggle”—a conscious struggle for a better reality. Even though there is a clear source of conflict that we expect Halley to passionately respond to, she refuses to confront it. Thus, different depictions of mundanity in “The Florida Project” are two sides of the same coin: while the mundane focus of Moonee’s scenes reveals her juvenile innocence, the mundanity of Halley’s scenes reveals her irresponsibility as an adult.

Both Moonee’s naivete and Halley’s immature indifference eventually come to an end when the child protection services arrive at their motel, and a social worker tries to take Moonee away from Halley. Distressed shouts from a mother echo against those of her daughter as the two become painfully aware of their reality and frantically struggle to resist its threatening grasp. For the first time, we witness emotional intensity and chaos on screen—and with this, the film ceases to appear mundane.

Audiences are initially thrown-off by the movie’s uneventful mundanity that results from Halley and Moonee’s inability to become conscious of their reality and confront all the pain it has to offer. Some may become frustrated, even, by the characters’ obliviousness and the shortage of effortful struggles that the Privileged often like to commend and admire from afar. But anyone who understands the pain of reality also understands the virtue of ignorance. This is why—despite being well-aware of the illogicality of making such a decision—the audiences are able to forgive Halley’s naivete even as it becomes the cause of her misery.

Only those who have frantically struggled in the hands of reality will be able to appreciate the blissfully oblivious nature of The Florida Project’s mundanity.

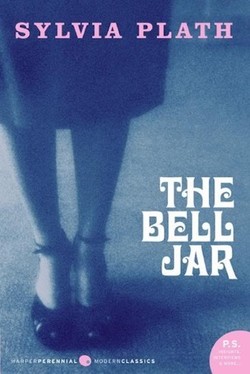

Personal purgatory in the mundane: an examination of The Bell Jar

A curious relationship exists between plotless mundanity and literary depictions of mental anguish characteristic of “personal purgatories[4]” in the modern world. Plotless mundanity is critical in capturing the essence of psychological torment, as understanding its intimacy and complexity calls for the absence of narrative distractions and momentous plot points that draw the readers’ focus away from the careful examination of a character’s affliction. Another reason why plotlessness and the mundane are critical to depicting mental anguish is because, in the very specific context of a personal psychological purgatory born from modern woes—such as isolation or identity crisis—one man’s triviality could very well be another man’s catastrophe, as the most insignificant and mundane detail could bring about the most disastrous bouts of despair and existential dread. Thus, “mundanity” is an essential factor that reflects the nature of personal purgatories often found in modern societies.

Sylvia Plath’s cult classic, The Bell Jar, gets into the quotidian, nitty-gritty details of the protagonist’s private psychological turmoil. The title of Plath’s novel is quite telling, as it depicts the image of the heroine, Esther Greenwood, being trapped inside the glass walls of a “bell jar”—a representation of Esther’s imprisonment within her psychological purgatory—and becoming isolated from the rest of the world. Esther’s mental anguish is mundane and distinctly modern in the sense that it derives not from an objectively critical crisis or a momentous incident, but is instead caused by an amalgamation of a subtle series of ordinary failures and disappointments in her life which are exacerbated by her perfectionistic and self-critical tendencies: qualities commonly promoted by the success-obsessed atmosphere of our contemporary society. Esther’s tipping point is her rejection from a prestigious Harvard writing program, and her inability to achieve this goal sends her into a depressive spiral. Like collapsing dominoes, this leads to a plethora of perceived disappointments in her relationships and a loss of self-identity as she finds herself failing miserably as a writer. Additionally, even though Esther experiences mental anguish, her emotions are rarely expressed as violent outbursts of grief and sorrow. Instead, her affliction is like a constant monotonic drone in the background that keeps her in a hypnotic state of dejection and melancholia.

Such characteristics are what make Esther’s anguish appear prosaic[5] rather than dramatic and striking; despite the protagonist’s personal purgatory being highly subjective, the sense of plotless mundanity that arises from the lack of epic quality in Esther’s breakdown is precisely what resonates with the readers. Through Esther, Plath draws a realistic portrait of the kinds of subtle and ordinary—but nonetheless destructive—struggles many of us experience in the modern world, such as self-doubt, estrangement, and the desire to excel. The rather banal cause of our despair and the bland, emotionally-subdued state of modern melancholia may lead some of us to question the validity of our suffering, asking ourselves whether we are truly worthy of our misery. However, Plath—through a meticulous dissection of Esther’s psyche and the mechanisms behind her torment—illustrates that such mundanity is an inherent characteristic of personal purgatories found in the modern world.

The mundane nature of Esther Greenwood’s psychological implosion in The Bell Jar brings attention to an universal aspect of our human condition that many of us overlook due to the perceived triviality and banality of modern woes. Thus, in-depth depictions of Esther’s psyche offer us a chance to become aware of the unrecognized complexities of—and solution to—our own personal purgatories.

Contemplation on the profundity of the mundane

The element of mundanity as presented in Lady Bird, The Florida Project, and The Bell Jar is profound because it artfully captures details of the universal human condition in all its flawed glory. Such films and novels shine a light unto the subtle, ordinary truths that make us human.

Peter Paik (Prof., Dept. of English Language & Lit.) states that “Films or novels in which very little actually happens tend to have a contemplative quality.” He continues, commenting on how “Mundanity prompts our focus on images that do not lend itself to advancing the story, and our contemplations on these images allow us to see the hidden significance of reality.” Indeed, these works encourage us to consciously meditate on the minutiae that come together to define our human experience, allowing us to feel an emotional catharsis in being able to comprehend something about ourselves and our reality that we were previously unaware of.

We reach a certain enlightenment, not from discovering something extraordinary, but from realizing the presence of a mundane piece of ourselves left hidden in plain sight.

[1] The New Oxford American Dictionary

[2] Medium

[3] Lady Bird

[4] Personal purgatories can best be explained as a private Apocalypse, where your house burns to the ground while the world continues going around.

[5] The characterization of Esther’s depression as being “prosaic” and “mundane” is not to downplay the significance of her or any other’s mental anguish, but to emphasize the subjective nature of such afflictions and how they frequently arise from ordinary, everyday causes.