An International Women’s Day special

WOMANHOOD IS a word that resonates with many. Nevertheless, it might be impossible to define the specifics of the word without some level of contention arising. Within womanhood, some may emphasize equal rights between sexes, while others remark on the beauty of femininity. The ambiguous, yet lasting relevance of this word and International Women’s Day falling this month of March may well be fit for introspection on "womanhood." As such, attempting to define the word might not do it much justice. Instead, comparing and contrasting artworks representative of distinct historical periods of Korean womanhood may be an adequate start to a more insightful understanding of the term.

Autonomy and enjoyment in Shin Yun-bok’s Scenery on a Dano Day

Scenery on a Dano Day currently displayed in the Ganseong Museum of Art[1], was painted by Joseon dynasty painter Shin Yun-bok as part of his Hyewon Telegraph Album, a 30-page album containing the artist’s folk paintings. Shin often depicted the daily lives of women in the Joseon era through his paintings under themes of “class tensions” and “love between opposite sexes[2].” What is most notable of Shin Yun-bok’s works, however, is the depiction of women as main characters in an era from which records about them are scarce.

Upon closer examination, one will notice two men secretly viewing a group of women, who are oblivious to their gaze, having an amenable afternoon. This depiction may indicate an existing tension between a woman’s innocent enjoyment and the male gaze. Yet, the two men do not hold center-stage in the painting: they are rather hidden. The women, on the other hand, are the main characters within the frame. Their long, luscious hair, colorful clothes, and varying postures as they go about their activities appear in stark contrast with the men, who are indiscernible from one another. Such composition demonstrates how patriarchal limitations against female enjoyment existed but were not explicitly enforced onto women of the Joseon era.

Indeed, the depictions of the women reveal sincere independence—to the extent in which they seem to be in their own microcosm of enjoyment. The most obvious signs of such autonomy are the semi-naked bodies against a backdrop of nature and a hanging swing-set. Some even depict a fourth-wall break as the illustrated women’s enjoyment is independent of not only the two men, but of the viewers. Conversely put, even us as viewers are excluded from their world. By becoming aware of the secret observers, the viewers are inevitably left out of partaking in the women’s enjoyment—becoming just a second batch of witnesses into a world of their own.

The women’s autonomy that can be interpreted from Scenery on a Dano Day may come across as revolutionary, given that the Joseon era is notable for its adoption of patriarchal Neo-Confucian values[3]. However, in an interview with The Yonsei Annals, Professor Choi Key-sook of Yonsei University’s Institute of Korean Studies, said there are many misconceptions surrounding the figure of women during the Joseon era.

For instance, the term Hyeon mo yang cheo, which literally translates to “wise mother and good wife”, is known to be a common ideal held onto—and perhaps even against—Korean women at that time. Nevertheless, research has shown that the term was never mentioned in Joseon records and was rather depicted by Japanese imperialism to fit Korea into its colonial purview. Furthermore, her research has demonstrated that Joseon women enjoyed more autonomy and received more esteem from the men in society. Upon thousands of written records left behind by literate men of that era, Choi has encountered several records of husbands referring to their wives in terms that either suggest equality or high respect. Words such as ji-gi, wae-u, and jaeng-u, that essentially refer to someone that is both one’s soulmate and mentor, were often used by husbands to revere their wives’ wise guidance.

According to Choi, she would define the identity of Joseon women as “working women.” Her research found that Joseon women, mainly those of the yang-ban[4] class, were highly active not only within the family nucleus, but also in their communities—often engaging in social service.

Reflecting on womanhood through artworks like Scenery on a Dano Day can reveal the importance of not only looking back to the past from time to time, but also rethinking the possibilities of what could have happened. According to Choi, studying the experience of womanhood in both the Joseon era and present times helped her and several of her students expand their perspective of a “female figure” in Korean society, leading to substantial conversations on what it truly means to be a woman.

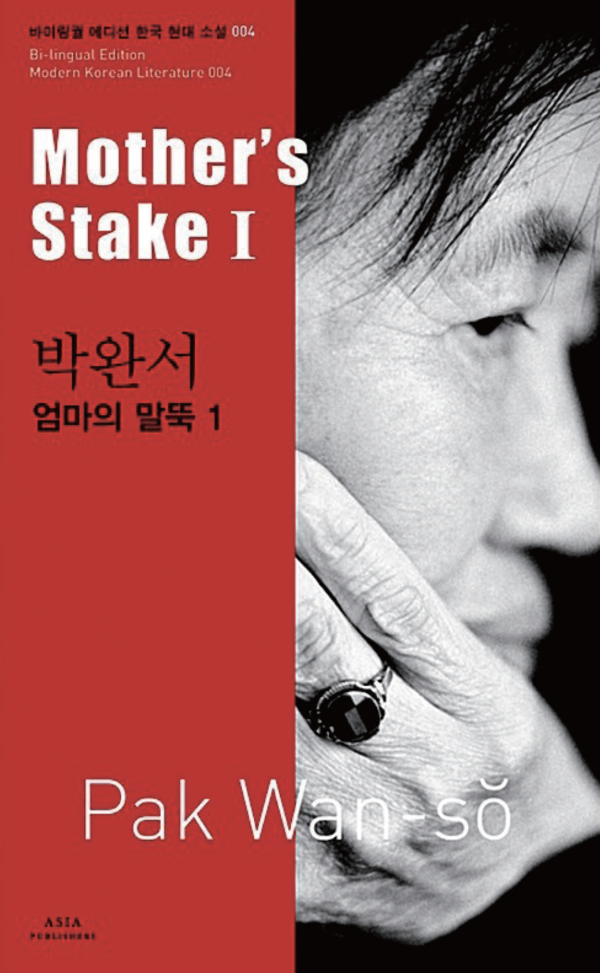

Outside the ‘gates’: female liberation in Park Wan-suh’s Mother’s Stake I

Mother's Stake I was published in 1982 by Korean novelist Park Wan-suh and is the first part of a trilogy[5]. Park often wrote in themes surrounding the changing social order as a consequence of foreign powers, the bad side of Korean capitalism, the effects of modernity on women, and the elderly[6].

The story is narrated uniquely in the first-person through the eyes of a young Korean girl who is forced to leave the comforts of the countryside to go to Seoul with her mother and brother during the country’s colonial period. The mother, upon the changes that modernity brought into Korea during Japanese colonization, zealously desires success and social validation through her children.

Through a mother-daughter relationship, this book examines how the state and the individual come together to bring about female liberation. More specifically, it questions the tension between modernity and tradition during colonial times in Korea and how female characters react to them. For instance, the narrator’s mother breaks all sorts of traditions that she is expected to fulfill. She leaves her in-law’s home in the countryside to go to Seoul, thereby rejecting her filial duties of jae-sa[7] during the festivities and taking care of them in their elderly state. She also breaks tradition by becoming a single mother and imposing an education on her daughter for her to become a “new woman.” According to the mother, such type of woman lives in Seoul, studies a lot, and wears a fashionable hi sa shi ga mi hairstyle[8] along with formal black attire. Above all, the mother’s desire for knowledge and freedom are intensely projected toward her daughter becoming a “new woman.” In the novel, the daughter says, “To Mother, a New Woman was a free soul who knew everything about the ways of the world and could do everything she wanted.”

The mother is desperate to witness freedom—something that she herself has never experienced—through her daughter. The mother holds onto new ideals that end up hindering her peace, freedom, and even end up affecting her daughter’s autonomy. Ultimately, Mother’s Stake I stands strong as a story of two women who, through rebellions on thought and action, attempted to escape their situations towards a liberated womanhood.

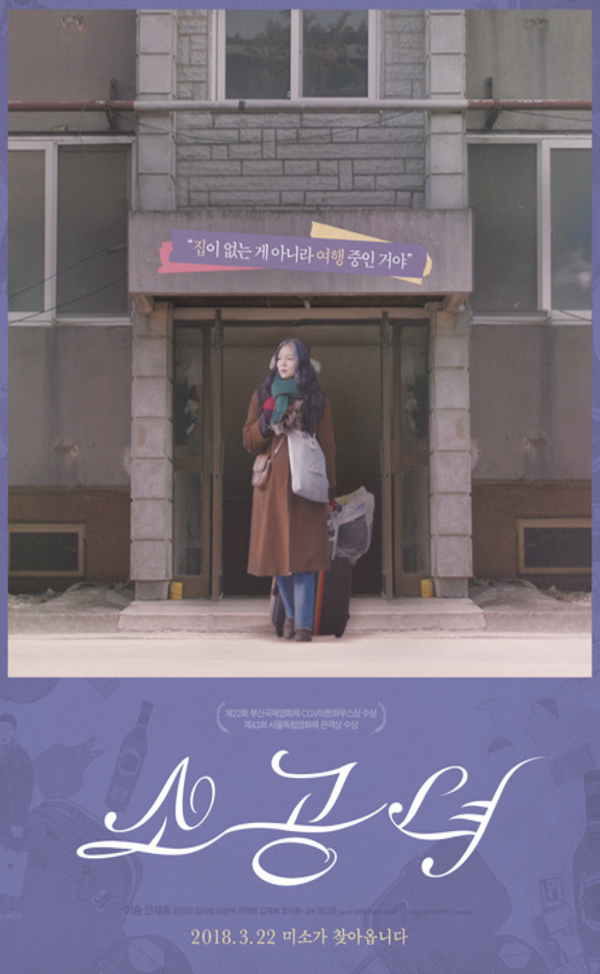

Pleasure is the antidote to strict gender norms in Jeon Go-woon’s Microhabitat

Microhabitat (So-kong-nyeo, in Korean) is a 2017 coming of age, independent film written and directed by Jeon Go-woon[9]. The story follows Mi-so, a woman in her mid-to-late twenties who often has a zero to negative balance on her budget. She works as a housekeeper, has no parents, and has a disease that makes her hair gray. Cigarettes, whiskey, and her boyfriend are the three quintessential things she considers necessary to get through life. When inflation raises the price of cigarettes, she makes the abrupt decision to leave her rental one-room to spare money for them. She writes-down a list of her college friends with whom she had a music band and decides to stay at each of their places until she finds a home.

So-kong-nyeo means “Little Princess” in English. This Korean term is derived from A Little Princess, a 1905 novel by American writer Frances H. Burnett. The novel is about a young woman characterized as being the ideal female figure[10]. While the ideal female figure of the 20th century may differ from that of the 21st century, as the film’s original name may suggest, the existence of social expectations on womanhood is as true today as it was over one hundred years ago. That is, there are, and have been, normative expectations on what women should strive for and, in contrast, should avoid. In the case of this film, centered around present-day Korean society, women should strive for what Mi-so’s friends have: marriage, children, and a successful career. On the other hand, they should avoid what Mi-so represents: alcohol, cigarettes, and men.

The film points out the near-impossible standards modern Korean society holds on womanhood. Upon visiting them, every single one of Mi-so’s friends’ lives are bound within the ideals of the ‘perfect daughter-in-law,’ ‘the successful career woman,’ and ‘the wise mother and good wife’—which causes them much emotional suffering. Mi-so, on the other hand, despite embodying nothing of what society deems appraisable in women and virtually everything of which it does not, carries herself with grace and, above all, is the owner of her pleasures and misfortunes. In Microhabitat, Mi-so is an example of a woman who established her dignity within a society that believes only women of certain characteristics are deserving of it.

* * *

In each of these works, womanhood holds a yearning for an existence outside of what seems to be already determined. In Scenery on a Dano Day, the women are in their own microcosm where the two peeking men become the outsiders—intruders into their autonomous moment of enjoyment. In Mother’s Stake I, the narrator’s introspective nature constantly rebels with what the outside world attempts to determines for her: being a successful new woman living in Seoul, leading a city life of order. In Microhabitat, Mi-seo’s quintessentials—alcohol, cigarettes, and her boyfriend—adopt their intrinsic element of pleasure but incorporate into them an element of courage and defiance towards a society that expects women to deviate from such “vices.” As we commemorate International Women’s Day this year, we may learn from these works that the date may be not so much about the celebration of specific characteristics or goals in womanhood. Rather, the commemoration of women every year on March 8 could be an opportunity to celebrate the limitless possibilities of experiencing womanhood.

[1] Kan-song Art and Culture Foundation

[2] Edujin

[3] AsiaSociety

[4] Yang-ban: The ruling class of the Koryeo and Joseon Dynasties

[5] Goodreads

[6] Encyclopedia of Korean Culture

[7] Jae-sa: Ancestral ceremonies

[8] Hi sa shi ga mi hairstyle: a Japanese women’s low pompadour hairstyle popularized during the country’s imperial period

[9] IMBD

[10] Oxford Languages