Retracing steps back to Mesopotamia

MESOPOTAMIA WAS the first city to appear on Earth. On the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, civilization took place, communities formed, writing systems were introduced, and ancient Mesopotamia was built. Although this civilization ended millions of years ago, it formed the foundation enabling the modern world to constantly evolve and is still an influential civilization today. The National Museum of Korea is currently offering a valuable opportunity to explore ancient Mesopotamia through an exhibition, Mesopotamia: Great Cultural Innovations, Selections from The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The exhibition is contributed by and in cooperation with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, sharing the privilege of exploring human history. It exhibits over 60 pieces of artifacts and consists of 3 sections: Cultural Innovation, Art and Identity, and The Age of Empires.

Cultural innovations: agriculture and cuneiform

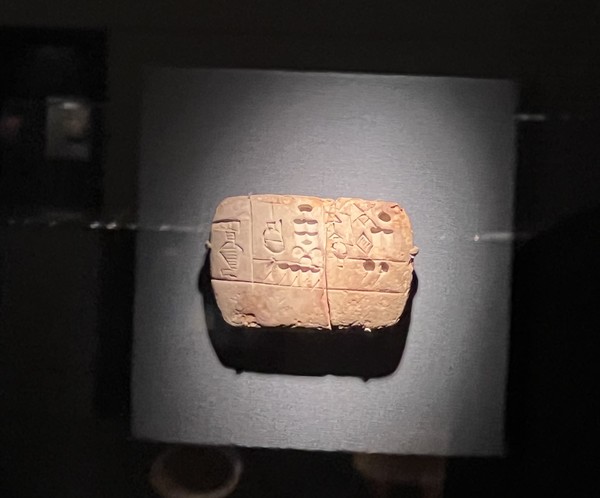

Mesopotamians were the first among humankind to invent a cuneiform writing system, which marked a major turning point in human history. This enabled them to express their abstract ideas concretely and leave records to pass on their skills to the next generation. A series of cuneiform tablets are chronologically displayed along the wall as one enters the first section.

Administrative account with entries concerning malt and barley groats is a cuneiform that includes the combination of numerical signs and pictographs. It can be regarded as ancient economic documentation of basic transactions. In the early years of the invention of writing, it was used to simply keep a record of the number of crops they harvested or the deliveries of animals. The accumulation of knowledge was possible over time which enabled the development of more complicated concepts.

In later years, cuneiform expanded to various genres, including historical and literary texts and medical and scientific accounts; complex forms of documents such as Fragment of a medical text, Dialogue document concerning succession and inheritance, and Multiplication table were discovered. It is fascinating to think that people at that time were able to develop and apply these sophisticated concepts. This reiterates the power of writing. Such a display of cuneiform reflects humans’ desire to constantly evolve, which the modern world resonates with.

Agriculture, the major economic activity at the time, was widespread and left abundant inventions and artifacts for archaeologists to uncover. *Fragment concerning canals* is one of the artifacts that proves the invention of canals and shows how agriculture was carried out during this period. The canals enabled the river to supply water for crops and stocks, irrigating the dry fields of the southern part of Iraq and providing Mesopotamians with abundant crops. According to Kim Gil-ju, the commentator at the museum, this allowed them to form the first agrarian society, and civilization was able to take place on a land without sufficient rain or resources.

Arts, the reflection of one’s identity

While cuneiform was a means for Mesopotamians to convert abstract ideas and beliefs into a concrete form, art was a great means of expressing one’s identity. The concept of identity was no longer only existent in one’s head as well.

Statue of Gudea is a portrait sculpture of King Gudea. It reveals Mesopotamians’ ethnic identity and what qualities they appreciate in a ruler. Portraiture is a medium that largely contributed to the Mesopotamian arts and often served to portray the ruler’s status. Mesopotamians’ concept of a “portrait” does not accommodate the general notion of portraiture, which intends to realistically depict a matter based on truth. Instead, it was more of an abstract concept for them; it represented people and what they associated them with. In this sculpture, Gudea is portrayed as a benignant figure. Through his clasped hands and large eyes that represent his attentive quality and sturdy arm muscles that emphasize his physical strength, it can be inferred that the qualities valued today for rulers or leaders are not so different from those of the ancient period[1]. Beyond the mere portrayal of the scenes seen on the surface, Mesopotamian portraiture reflects how they interpreted and perceived the rulers to be. This highlights humankind’s great ability to conceptualize and visually express ideas that exist in their mind.

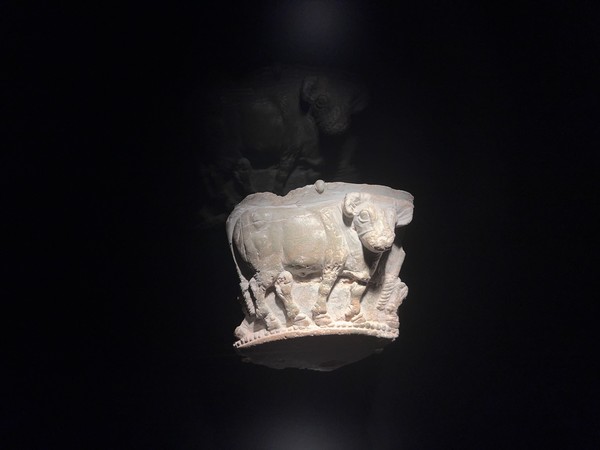

Fragment of a bowl with a frieze of bulls in relief is a decoration on a bowl, which is humankind’s first creation made of nature and frequently appears in the Mesopotamian arts. Bulls hold symbolic significance to Mesopotamians and emerge in many different forms of art, including sculptures and seals; they signify power and virility. While they realistically depicted the details of a bull, oddly, the head is completely turned outward to face the viewer. This is an example of how they incorporated their subjective interpretation of a certain matter through their creation.

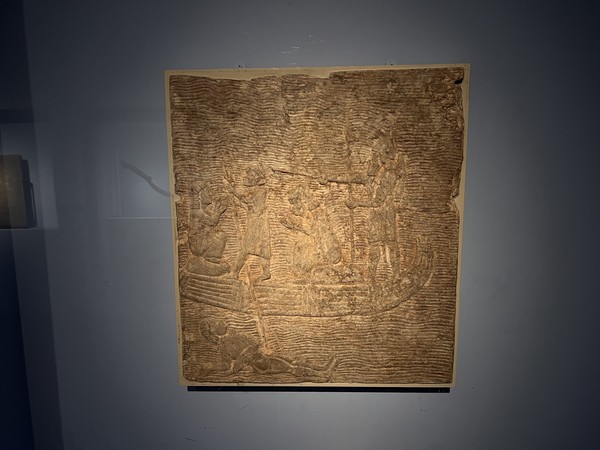

Assyrian soldier conducting captives across the water is wall art that reveals the societal structure at the time. By positioning each social class from the top to the bottom in the order of the king, soldiers, prisoners of war, and enemies, it amplifies the hierarchy and emphasizes the greatness of Assyrians. A form of hierarchy existed even in the ancient city, proving that the formation of a community ultimately and naturally follows the emergence of a hierarchy—it is simply inevitable.

Legacies of the Mesopotamian civilization

Even though Mesopotamian civilization and the modern world are millions of years apart, they are closely connected and the civilization left legacies in various aspects of the modern day. Both in the past and present, humankind has constantly desired to make sense of their surroundings and where they fit in in this universe[1]. Mesopotamians were able to achieve this through records and inheritance of various skills. People of contemporary society inherited what Mesopotamians achieved in the past. It was not simply the invention of writing that achieved today’s advanced technology, but it was their ingenuity and ability to conceptualize. In a further interview with The Yonsei Annals, Kim explained that the Mesopotamian civilization offered a foundation of various philosophical aspects, and the accumulation of academic knowledge, such as astronomy, was inherited by ancient Greece. She adds that the concept of religion and rituals that glorify gods is another prominent legacy. Although the Greek gods were more complexly subdivided and Mesopotamian gods were relatively straightforward, they share the common concept of early religion and the idea that radical motivation for one’s religious belief comes from horror and gratitude towards gods.

In a sense that “the true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection and the rest are copy[2],” Mesopotamian art has been a great inspiration for modern and contemporary art. Picasso’s Cubism is an example of this. Mesopotamian arts that thrive to showcase their ingenious perception rather than merely relying on surface-level observation resembles Cubism, which sees the value in creating an abstract output. Although they employ different art mediums, how they perceive art is similar. The bull with its head completely turned outward rejects a traditional realistic view and prioritizes abstract perception, which is what Picasso thrived to achieve through his Cubist artworks.

The exhibition goes beyond providing informative historical knowledge; it offers a space to connect the two different periods. The viewers are given a valuable opportunity to seek the preciousness of the little things we take for granted—the ability to contemplate sophisticated matters and to express abstract ideas in a visually recognizable form. It also enlightens the viewers how the ancient Mesopotamian civilization has a lasting impact to this day.

Period: July 22, 2022, to Jan. 28, 2024

Entry Hours: 10:00-18:00, 10:00-21:00 (Wednesdays and Saturdays)

Admission: Free

Address: Mesopotamian Gallery at the World Art Gallery of the National Museum of Korea, 137 Seobinggo-ro, Yongsan-gu, Seoul

[1] National Museum of Korea

[2] Michelangelo Buonarroti