An exploration of horror

PURE CATHARSIS is a phrase that could accurately epitomize the emotions provoked by the horror genre. Horror films reject all expectations of “watching a movie” by offering us anything but a wholesome or relaxing experience. They keep us on the edge of our seats or pinching the arms of those next to us. Above all, they create a gap in our knowledge of the world’s possibilities, causing us to spiral into a black hole of merciless mystique. To celebrate the spooky month of October, The Yonsei Annals dives into the psychology and psychoanalysis behind why humans feel—and actively seek to consume—horror, be it in films of creatures lurking in shadowy depths of the ocean or even within ourselves.

About the horror genre

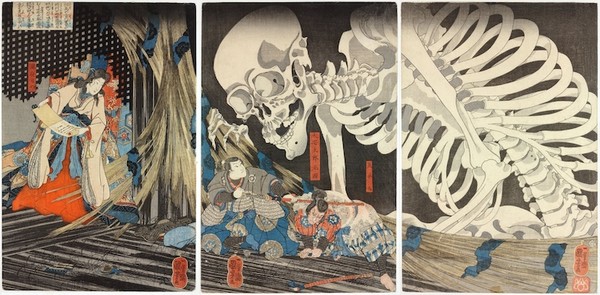

Having its roots in ancient folkloric storytelling, the horror genre has maintained its relevance across time and space[1]. Its narrative’s main purpose is to generate fear in the spectator through supernatural creatures, such as vampires or ghosts, or psychological fears[2]. Accordingly, some of the most common subgenres of horror films are demonic possession, slasher, zombie, and psychological[1].

The beginnings of horror films are closely tied to the advent of cinema. One of the first horror films, Le Manoir du Diable (The House of the Devil), released in 1896, was directed by French filmmaker Georges Méliès, a pioneer in the world of cinema. In the 1910s, horror films centered around adaptations of literary works. Stories of supernatural entities, such as Edison Studio’s Frankenstein, are distinctive from this era[3]. Literature ceased to be the main source of inspiration during the 1920s and 1930s. These years are considered the Golden Age for horror films due to the number of classic films produced, as well as the fact that these decades marked the transition between silent and sound cinema. There was a remake of Frankenstein in 1931, and The Mummy was released a year after[3].

The genre saw a substantial shift in focus in the 1940s and 1950s, as several horror films became interpretations of the wars occurring at the time. Specifically in the science fiction horror genre, films such as Godzilla and The War of the Worlds spoke for the fears of genetic mutation due to the radiation caused by nuclear bombs[3]. The years that followed, the 1970s and 1980s, marked intense creative changes in the horror genre. There was a cultural obsession with humans possessed by the devil, with films like The Exorcist becoming a classic in the supernatural horror genre. In addition, the slasher genre exemplifies the 1980s horror films with works such as A Nightmare on Elm Street and Texas Chainsaw Massacre[3].

The gore-lad horror films of the past decades soon became lackluster to the audience due to their repetitive format. Thus, during the 1990s, a more satirical approach to the horror genre paved the way for horror comedy, with the 1996 film Scream being the first to execute satire within horror[4]. Thereafter, the 2000s and 2010s saw the rise of zombie movies, such as World War Z or the Resident Evil series. Additionally, horror films became more direct in their sociopolitical commentary: most notable among such films is director Jordan Peele’s works such as the 2017 film Get Out[3].

Horror and psychology

No matter how gruesome and traumatizing a horror movie claims itself to be, it is no lie that there will still be people who seek it. In fact, the greater the feelings of horror the film can creat, the greater engagement the film receives. Some psychological reasons why people consume horror are to experience stimulation, satisfy one’s curiosity about the dark side of the human psyche, and derive pleasure from the seemingly adverse effects of horror on emotions[7].

The latter can be better understood through Dr. Dolf Zillman’s excitation transfer theory from 1983. The theory states that “emotional responses can be intensified by arousal from other stimuli not directly related to the stimulus that originally provoked the emotional response[8].” That is, the pleasure one feels upon going through the adverse emotions provoked by horror films is often derived from the intensified “residual arousal” of other emotions that the horror film caused[5].

Several horror films catalyze these excitation transfers. A classical film would be director Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975). In this film, the good people triumph over evil, in this case, the shark. The intense feelings of displeasure and discomfort the audience experience by watching a creature devour innocent humans are maintained within and then transferred into even more intense feelings of satisfaction and pleasure from an outcome where the humans triumph. The film’s intention of first building up negative emotions can be seen through the iconic camera movement, the dolly zoom. A dizzying shot pioneered by Alfred Hitchcock, it zooms into the subject of focus, while zooming out of its background, intensifying emotions of helplessness, despair, and fear.

The above theory is similarly articulated in scholar Noel Carroll’s article “Why Horror?” He explains that within the horror felt while watching a frightening film lies the feeling of pleasure. What distinguishes horror films from other genres is that they do not directly render their audience with pleasing elements. Rather, it manipulates negative emotions of “disquiet, distress, and displeasure” into a pleasurable sensation[5].

While research on why people actively seek such afflictions is extensive, it is still unclear exactly why humans feel “horror” in the first place. A few theories have attempted to address such a question. For instance, robotics Professor Masahiro Mori’s Uncanny Valley theory from 1970 explains why human-like entities, whose humanity we perceive to be ambivalent, cause adverse emotions in us[8]. This is explained by a two-dimensional graph that describes the relationship between an object’s affinity to humans and its human likeliness. For instance, an industrial robot remains close to the origin of the graph, for it is not an object that humans often interact with, and it much less resembles us in any way. However, this graph contains a “dip,” called the uncanny valley, that corresponds to any object that scores extremely low in affinity to humans, yet above average in human likeliness. An example of an object in the uncanny valley is a human-like robot: humans have a low affinity for it, yet it undoubtedly resembles us.

Horror and psychoanalysis

A field that can render even further perspectives on horror films’ relationship to the uncanny is psychoanalysis. A discussion of the psychoanalytic view of the human psyche is necessary prior to delving into their theories. Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud categorized the psyche into three parts: the id, the ego, and the superego. The id is the unconscious. It operates on the pleasure principle, meaning it demands the gratification of basic urges, needs, and desires. The id is divided into two parts: the life instinct “Eros” and the death instinct “Thanatos.” The former enables individuals to survive by safely satisfying basic needs such as respiration, eating, and sex. Meanwhile, the latter is the set of destructive forces within all human beings that pleases one’s desires[6]. Furthermore, the ego is the part of one’s personality which is in contact with the outer world. It expresses—or suppresses—the id’s impulses according to what it deems realistic and socially acceptable[6].

“Uncanny” is a key word in understanding, psychoanalytically, why humans feel horror. In an interview with the Annals, Astrid Lac (Prof., UIC, Common Curriculum) explained that the term “uncanny,” is better understood as Freud defined it in the original German: unheimlich. Un (negative) and heim (home) together denote “not of home” or “not familiar.” Altogether, the word comes to describe that which feels outside of our usual associations.

There are two registers of the uncanny that bring about the feeling of horror. The first revolves around the surmounted history of the human species. Lac explains, “Our primitive ancestors thought of the world as a magical space, wherein with thoughts alone they could make things happen, hurt someone, for example. ‘Civilized,’ of course, we no longer indulge in these beliefs. However, such surmounted primitive beliefs can and often do return to us.” For example, in seeing the same number—especially such superstitious numbers as 4 in East Asian countries or 13 in Western countries—repeatedly in different contexts throughout one’s day, one would read a certain meaning into this repetition and be horrified by it. Thereby transpires a relapse into magical thinking: “One would not think of this repetition as a mere coincidence but experience it as foreboding. This is magic. It triumphs over one’s power of reason.”

The second register has to do with the individual subject’s “repressed material.” The German philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling has a fitting formulation that Freud found useful: “Unheimlich is the name for everything that ought to have remained ... secret and hidden but has come to light.” Lac explains, “The secret referred to in this quote is the material ‘repressed’ by the ego. It is the return of the ‘repressed material’ which, when brought to light, the ego reacts to with horror.” That is, horror is caused when repressed material finds its way from the id to the conscious ego. Lac adds that Schelling’s formulation is applicable to the aforementioned “surmounted” history of the species, which explains why cinema tends to use superstitions as triggers of horror.

On the question of Eros and Thanatos, two of the major Freudian concepts, Lac situates horror as “one kind of staging of the antagonism between them.” Thanatos follows whatever allows libidinal satisfaction. It spends the libido and thereby pushes the subject closer to death. Lac renders the example of a sex addict. Such person, by engaging in continuous sex without allowing his or her body to rest, would ultimately exhaust himself or herself and approach death. Eros is nothing other than a detour to death. Instead of gaining a more immediate gratification from watching pornography, for instance, one would engage another person in a relationship, which is far more complicated than immediate gratification. By taking the more indirect way of satisfying one’s libidinal needs, one makes the journey to death longer. Horror occurs when Thanatos is triumphing over Eros. It is horrifying to perceive one’s libidinal urges be satisfied to serve Thanatos. To make the matter more complicated, Lac explains, “By having the reaction of horror, one is already stepping on the brakes on the path to death. Horror is a life-preserving, not to say healthy, reaction of the Erotic ego to Thanatos of the id. Horror is defense against death.”

A horror film that embodies such a line of thinking is British director Clive Barker’s 1987 film Hellraiser. More specifically, the characters of the Cenobites—and their interactions with their victims—demonstrate the id’s repressed material coming into conflict with the ego once it is exposed. The Cenobites are “a race of God-like sadists who [torture] their human victims with sensual experiences far beyond their (or our) tired understanding of pleasure and pain[10].” They are not only horrifying due to their low affinity yet above average similarity in looks to humans, as the dip in Masahiro’s uncanny valley suggests; rather, they cause such intense feelings of threat, disgust, and horror because they are representations of our own repressed desires that have come to light. Indeed, part of the Cenobites’ repelling allure lies in the fact that they too were once human. Furthermore, rather than arbitrarily seeking for victims to torture, they are summoned by the desires of their victims[11].

* * *

Horror is a universal and multifaceted experience, which elucidates its ancient origins as a genre of fiction. From psychology, one can learn that horror often generates pleasure given the surplus of cathartic emotions the film initially creates. Additionally, objects or entities with ambiguous humanity engender an air of uncanniness, which is a cause for horror in humans. In psychoanalysis, such a notion of uncanniness is further elaborated through diverse interplays between the id and the ego, as well as Eros and Thanatos. While one need not resort to horror films or engage in theoretical understandings of it to feel horror, such references can introduce and guide us in acknowledging the workings of horror around us and within ourselves.

[1] The Los Angeles Film School

[2] Britannica

[3] New York Film Academy

[4] The Signal

[5] The Aesthetics and Psychology Behind Horror Films

[6] Simply Psychology

[7] Harvard Business Review

[8] American Psychologist Association

[9] The Oxford Scientist

[10] Roger Ebert

[11] Jonas Ceika