Kim Eun-sung and Kim Seo-kyung, sculptors standing by victims of war

HAVE YOU seen the Comfort Women Statue in front of the Japanese Embassy or even at the Ewha Street nearby Yonsei University? Kim Eun-sung and Kim Seo-kyung, who have been married for 26 years, are the sculptors who created this statue that arouses deep empathy from many South Korean people. The artists set up the Comfort Women Statue in 25 places in Korea and 2 places in the United States, in order to memorialize former Korean comfort women who were forcibly drafted for military sex slavery by Imperial Japan during World War II. The Yonsei Annals met Kim Seo-kyung to listen to her stories and plans as an artist who wants to bring peace and happiness to people through her sculptures.

Annals: What led you two to make the Comfort Women Statue?

Kim: One Wednesday in 2011, my husband passed by the Japanese Embassy in Seoul and saw people protesting for an apology to the victims of sexual slavery in the Japanese military during World War II. We were so astonished to find out that the issue was not yet resolved even though 20 years had passed since 1991, when Kim Hak-sun first testified about her suffering during the war and disclosed the existence of former comfort women. As sculptors, we wanted to take part in supporting their voices, so we visited the Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan. At that time, the council was planning to build a peace monument to mark the 1,000th Wednesday demonstration, so we worked together to create the monument. A bronze Comfort Women Statue, which is officially called the Peace Monument, was placed in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul on Dec 14, 2011.

Annals: What inspired you to make the Comfort Women Statue in the shape of a young girl?

Kim: There were various ideas for its design but we decided to create a human body sculpture, since it was our specialty. We first thought of making a statue of a person standing bravely, but later changed to a statue of a young Korean girl. The comfort women had to go through horrible sufferings when they were just teenage girls, so we thought the statue must be an image that commemorates their lost youth. Since these former comfort women, who now have become old, sit on chairs to protest in every Wednesday demonstration, we sculpted a young short-haired girl sitting on a chair next to an empty chair symbolically left behind by deceased former comfort women. The little bird on the girl’s shoulder symbolizes freedom and peace, and her shadow cast on the ground in the image of a bent old woman implies the comfort women’s longstanding resentment. A little butterfly in the heart of the shadow represents a wish to resolve their deep sorrow.

Annals: Did you face any difficulties while making the statue?

Kim: Only when we embraced the comfort women’s pains as our own could we create a statue that truly resembled them. It was very painful and difficult to empathize with their sufferings, so I was heartbroken and in tears during the work. In the midst of this emotional turmoil, the Japanese government exerted political pressure to hamper the establishment of the statue in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul. There was no pressure upon us personally, but I was infuriated at the uncomfortable and tense situation itself. It was under this continuous pressure exerted by the Japanese government that we redesigned the Comfort Women Statue to clench her fists confidently on her lap to convey the former comfort women’s strong will to receive an apology.

Annals: Why did you recently start a fund-raising project with miniature Comfort Women Statues?

Kim: The Comfort Women Statue embodies decades of suffering and protest, and people have cared deeply for it by dressing it with a coat or scarf. For this reason, the Japanese government’s request to remove the statue from in front of the Japanese Embassy in exchange for ¥1 billion has hurt South Koreans’ dignity. After Dec. 28, 2015, when the South Korea-Japan Accord on Comfort Women was announced, many people furious at the news contacted us. Some people said that they would like to take the Comfort Women Statue with them while traveling, to let foreigners know about it. Some others even said that they would like to financially support making more statues. So last January, with about 20 of these people, we began four fund-raising projects on Tumblbug, including this one. We aim to assert that South Koreans do not need ¥1 billion, but a sincere apology from the Japanese government. Through a spreading movement of statues, we expect to express our anger about the issues related to comfort women and uphold our dignity.

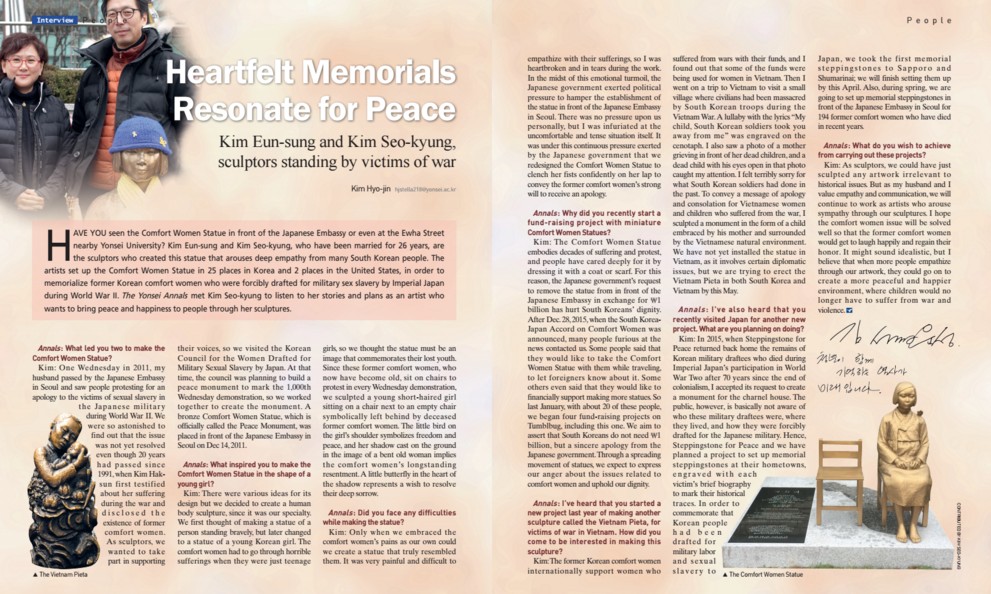

Annals: I’ve heard that you started a new project last year of making another sculpture called the Vietnam Pieta, for victims of war in Vietnam. How did you come to be interested in making this sculpture?

Kim: The former Korean comfort women internationally support women who suffered from wars with their funds, and I found out that some of the funds were being used for women in Vietnam. Then I went on a trip to Vietnam to visit a small village where civilians had been massacred by South Korean troops during the Vietnam War. A lullaby with the lyrics “My child, South Korean soldiers took you away from me” was engraved on the cenotaph. I also saw a photo of a mother grieving in front of her dead children, and a dead child with his eyes open in that photo caught my attention. I felt terribly sorry for what South Korean soldiers had done in the past. To convey a message of apology and consolation for Vietnamese women and children who suffered from the war, I sculpted a monument in the form of a child embraced by his mother and surrounded by the Vietnamese natural environment. We have not yet installed the statue in Vietnam, as it involves certain diplomatic issues, but we are trying to erect the Vietnam Pieta in both South Korea and Vietnam by this May.

Annals: I’ve also heard that you recently visited Japan for another new project. What are you planning on doing?

Kim: In 2015, when Steppingstone for Peace returned back home the remains of Korean military draftees who died during Imperial Japan’s participation in World War II after 70 years since the end of colonialism, I accepted its request to create a monument for the charnel house. The public, however, is basically not aware of who these military draftees were, where they lived, and how they were forcibly drafted for the Japanese military. Hence, Steppingstone for Peace and we have planned a project to set up memorial steppingstones at their hometowns, engraved with each victim’s brief biography to mark their historical traces. In order to commemorate that Korean people had been drafted for military labor and sexual slavery to Japan, we took the first memorial steppingstones to Sapporo and Shumarinai; we will finish setting them up by this April. Also, during spring, we are going to set up memorial steppingstones in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul for 194 former comfort women who have died in recent years.

Annals: What do you wish to achieve from carrying out these projects?

Kim: As sculptors, we could have just sculpted any artwork irrelevant to historical issues. But as my husband and I value empathy and communication, we will continue to work as artists who arouse sympathy through our sculptures. I hope the comfort women issue will be solved well so that the former comfort women would get to laugh happily and regain their honor. It might sound idealistic, but I believe that when more people empathize through our artwork, they could go on to create a more peaceful and happier environment, where children would no longer have to suffer from war and violence.

Kim Hyo-jin

hjstella218@yonsei.ac.kr