Delving into art that is traditional yet unconventional, colorful yet painful

A CROWN of bright yellow daffodils, magenta hibiscus, and orange dahlias outline the portrait of a woman adorned with gold nuggets and rainbow beads. At first glance, we picture Frida Kahlo and her famous self-portraits. Yet Frida isn’t the only pioneer of colorful, vibrant art. A traveler, writer, and artist, Chun Kyung-ja expressed her pain and sorrow through spiritual motifs and saturated hues. Chun is well known as a figure of contemporary and modern Korean art, and her works deal with unconventional themes portrayed through original, novel methods. Like Frida’s, Chun’s colorful paintings ironically mirror solitude and trauma, exploring her emotions associated with personal experiences of war and travel. These works are open to the public eye at the Seoul Museum of Art exhibition: Chun Kyung-ja, Everlasting Narcissist.

Unveiled, at last

Chun Kyung-ja was born and raised in Go-heung county, South Jeolla province. She then moved to Japan to pursue a career in the arts, despite her parents’ wishes toward a medical career. Chun’s talent was first widely acknowledged in 1952 through her iconic work A Mode of Life, a painting of thirty-three snakes intertwined, forming a massive clutter. The beginning of the repetitive imagery of snakes is known to be the critical point in Chun’s artistic journey, as the obscure motif was a product of two failed marriages, the Korean war, and the loss of her sister.

Trouble still followed the artist even up to the early 90s, when the artist herself claimed that the painting Beautiful Woman exhibited at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) was a forgery and not her own work. Chun’s family sued the gallery for profiting off inauthentic work. Eight years later, a man named Kwon Choon-sik confessed to having illustrated the counterfeits. After endless controversy, an official statement acknowledging the gallery’s violation of copyright laws and defamation was released by the Seoul Central District Prosecutor’s Office in 2016, ending the debate after 25 years. Unfortunately, the statement was announced a year after the artist’s passing.

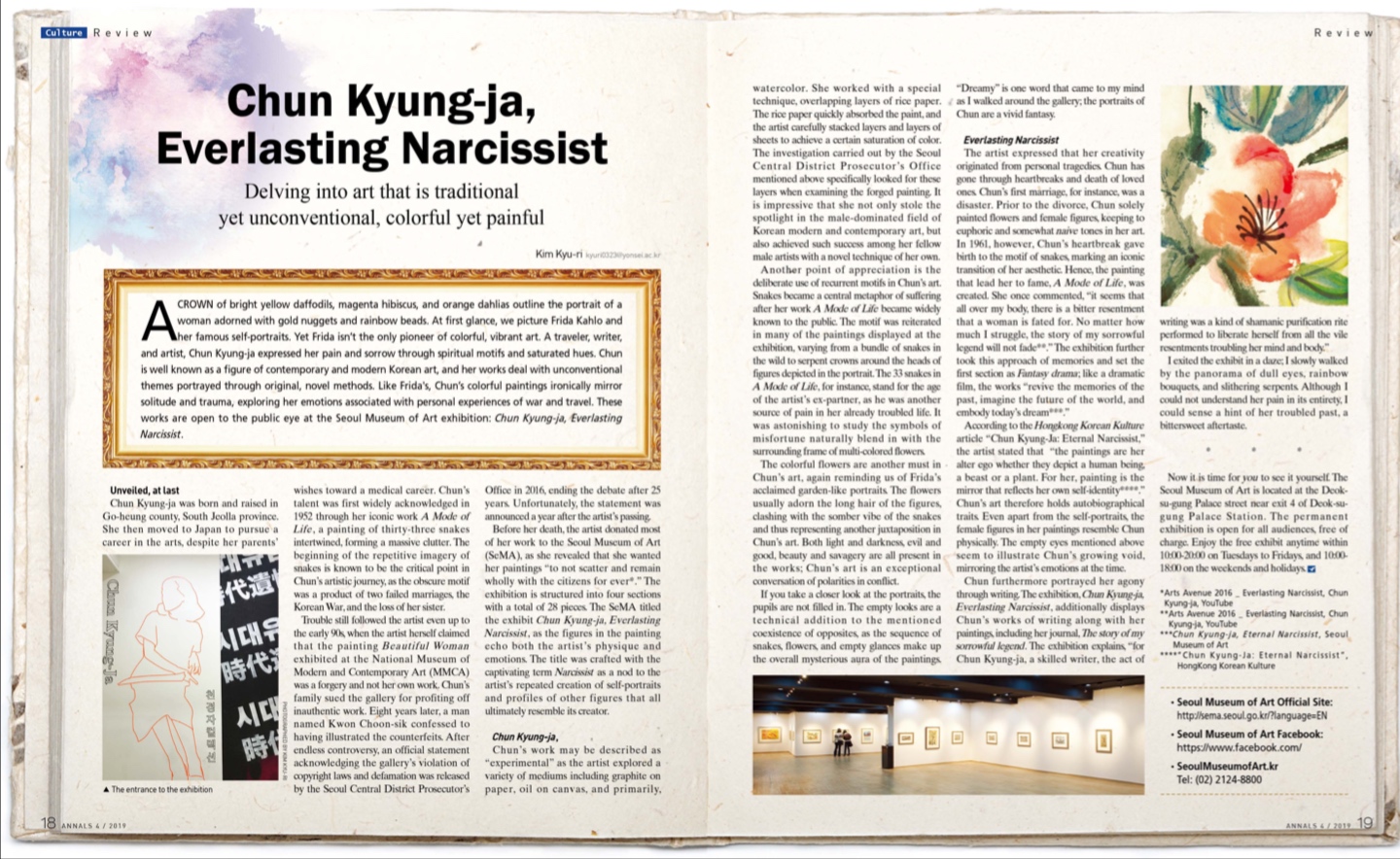

Before her death, the artist donated most of her work to the Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA), as she revealed that she wanted her paintings “to not scatter and remain wholly with the citizens for ever*.” The exhibition is structured into four sections with a total of 28 pieces. The SeMA titled the exhibit Chun Kyung-ja, Everlasting Narcissist, as the figures in the painting echo both the artist's physique and emotions. The title was crafted with the captivating term Narcissist as a nod to the artist’s repeated creation of self-portraits and profiles of other figures that all ultimately resemble its creator.

Chun Kyung-ja

Chun’s work may be described as “experimental” as the artist explored a variety of mediums including graphite on paper, oil on canvas, and primarily, watercolor. She worked with a special technique, overlapping layers of rice paper. The rice paper quickly absorbed the paint, and the artist carefully stacked layers and layers of sheets to achieve a certain saturation of color. The investigation carried out by the Seoul Central District Prosecutor’s Office mentioned above specifically looked for these layers when examining the forged painting. It is impressive that she not only stole the spotlight in the male-dominated field of Korean modern and contemporary art, but also achieved such success among her fellow male artists with a novel technique of her own.

Another point of appreciation is the deliberate use of recurrent motifs in Chun’s art. Snakes became a central metaphor of suffering after her work A Mode of Life became widely known to the public. The motif was reiterated in many of the paintings displayed at the exhibition, varying from a bundle of snakes in the wild to serpent crowns around the heads of figures depicted in the portrait. The 33 snakes in A Mode of Life, for instance, stand for the age of the artist’s ex-partner, as he was another source of pain in her already troubled life. It was astonishing to study the symbols of misfortune naturally blend in with the surrounding frame of multi-colored flowers.

The colorful flowers are another must in Chun’s art, again reminding us of Frida’s acclaimed garden-like portraits. The flowers usually adorn the long hair of the figures, clashing with the somber vibe of the snakes and thus representing another juxtaposition in Chun’s art. Both light and darkness, evil and good, beauty and savagery are all present in the works; Chun’s art is an exceptional conversation of polarities in conflict.

If you take a closer look at the portraits, the pupils are not filled in. The empty looks are a technical addition to the mentioned coexistence of opposites, as the sequence of snakes, flowers, and empty glances make up the overall mysterious aura of the paintings. “Dreamy” is one word that came to my mind as I walked around the gallery; the portraits of Chun are a vivid fantasy.

Everlasting Narcissist

The artist expressed that her creativity originated from personal tragedies. Chun has gone through heartbreaks and death of loved ones. Chun’s first marriage, for instance, was a disaster. Prior to the divorce, Chun solely painted flowers and female figures, keeping to euphoric and somewhat naive tones in her art. In 1961, however, Chun’s heartbreak gave birth to the motif of snakes, marking an iconic transition of her aesthetic. Hence, the painting that lead her to fame, A Mode of Life, was created. She once commented, “it seems that all over my body, there is a bitter resentment that a woman is fated for. No matter how much I struggle, the story of my sorrowful legend will not fade**.” The exhibition further took this approach of memories and set the first section as Fantasy drama; like a dramatic film, the works “revive the memories of the past, imagine the future of the world, and embody today’s dream***.”

According to the Hongkong Korean Kulture article “Chun Kyung-Ja: Eternal Narcissist,” the artist stated that “the paintings are her alter ego whether they depict a human being, a beast or a plant. For her, painting is the mirror that reflects her own self-identity****.” Chun’s art therefore holds autobiographical traits. Even apart from the self-portraits, the female figures in her paintings resemble Chun physically. The empty eyes mentioned above seem to illustrate Chun’s growing void, mirroring the artist’s emotions at the time.

Chun furthermore portrayed her agony through writing. The exhibition, Chun Kyung-ja, Everlasting Narcissist,additionally displays Chun’s works of writing along with her paintings, including her journal, The story of my sorrowful legend. The exhibition explains, “for Chun Kyung-ja, a skilled writer, the act of writing was a kind of shamanic purification rite performed to liberate herself from all the vile resentments troubling her mind and body.”

I exited the exhibit in a daze; I slowly walked by the panorama of dull eyes, rainbow bouquets, and slithering serpents. Although I could not understand her pain in its entirety, I could sense a hint of her troubled past, a bittersweet aftertaste.

* * *

Now it is time for you to see it yourself. The Seoul Museum of Art is located at the Deok-su-gung Palace street near exit 4 of Deok-su-gung Palace Station. The permanent exhibition is open for all audiences, free of charge. Enjoy the free exhibit anytime within 10:00-20:00 on Tuesdays to Fridays, and 10:00-18:00 on the weekends and holidays.

*Arts Avenue 2016 _ Everlasting Narcissist, Chun Kyung-ja, YouTube

**Arts Avenue 2016 _ Everlasting Narcissist, Chun Kyung-ja, YouTube

***Chun Kyung-ja, Eternal Narcissist, Seoul Museum of Art

****“Chun Kyung-Ja: Eternal Narcissist”, HongKong Korean Kulture

Kim Kyu-ri

kyuri0323@yonsei.ac.kr