The challenges North Korean defector youths face when resettling in South Korea

“THE ONLY divided country in the world.” This is one of the more infamous titles that Korea holds within the global community. It has been over 70 years since the Korean peninsula split into South Korea and North Korea, during which many North Koreans crossed the barbed wire to resettle here. There are various reasons North Korean defectors become motivated to flee to South Korea; economic difficulties, political oppression, and in pursuit of an overall better living situation. However, while they live on South Korean soil, several barriers continue to leave North Korean defectors feeling estranged from a land that is at once familiar yet foreign.

Resettling south over the border

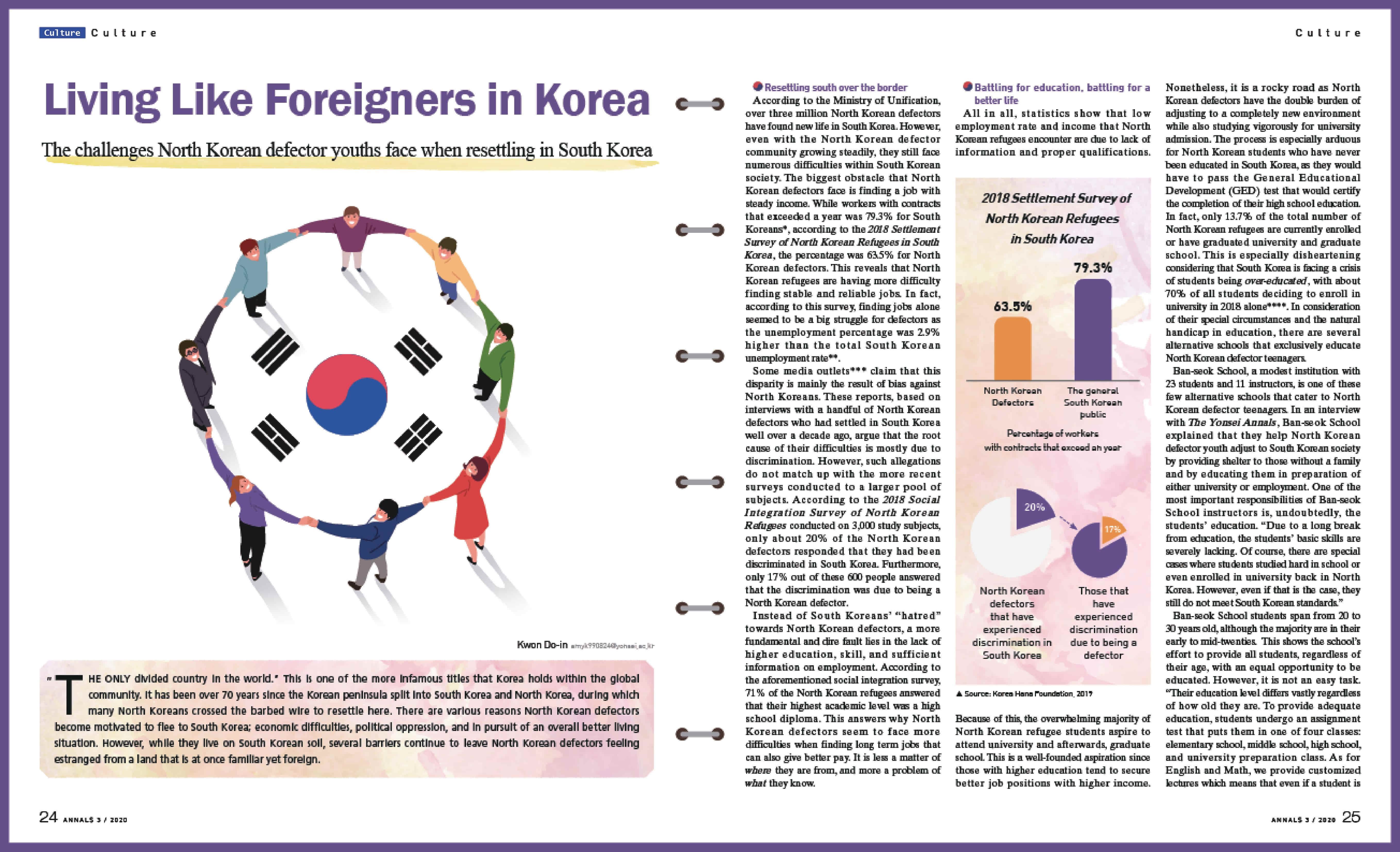

According to the Ministry of Unification, over three million North Korean defectors have found new life in South Korea. However, even with the North Korean defector community growing steadily, they still face numerous difficulties within the South Korean society. The biggest obstacle that North Korean defectors face is finding a job with steady income. While workers with contracts that exceeded a year was 79.3% for South Koreans*, according to the 2018 Settlement Survey of North Korean Refugees in South Korea, the percentage was 63.5% for North Korean defectors. This reveals that North Korean refugees are having more difficulty finding stable and reliable jobs. In fact, according to this survey, finding jobs alone seemed to be a big struggle for defectors as the unemployment percentage was 2.9% higher than the total South Korean unemployment rate**.

Some media outlets*** claim that this disparity is mainly the result of bias against North Koreans. These reports, based on interviews with a handful of North Korean defectors who had settled in South Korea well over a decade ago, argue that the root cause of their difficulties is mostly due to discrimination. However, such allegations do not match up with the more recent surveys conducted to a larger pool of subjects. According to the 2018 Social Integration Survey of North Korean Refugees conducted on 3,000 study subjects, only about 20% of the North Korean defectors responded that they had been discriminated against in South Korea. Furthermore, only 17% out of these 600 people answered that the discrimination was due to being a North Korean defector.

Instead of South Koreans’ “hatred” towards North Korean defectors, a more fundamental and dire fault lies in the lack of higher education, skill, and sufficient information on employment. According to the aforementioned social integration survey, 71% of the North Korean refugees answered that their highest academic level was a high school diploma. This answers why North Korean defectors seem to face more difficulties when finding long term jobs that can also give better pay. It is less a matter of where they are from, and more a problem of what they know.

Battling for education, battling for a better life

All in all, statistics show that low employment rate and income that North Korean refugees encounter are due to lack of information and proper qualifications. Because of this, the overwhelming majority of North Korean refugee students aspire to attend university and afterwards, graduate school. This is a well-founded aspiration since those with higher education tend to secure better job positions with higher income. Nonetheless, it is a rocky road as North Korean defectors have the double burden of adjusting to a completely new environment while also studying vigorously for university admission. The process is especially arduous for North Korean students who have never been educated in South Korea, as they would have to pass the General Educational Development (GED) test that would certify the completion of their high school education. In fact, only 13.7% of the total number of North Korean refugees are currently enrolled or have graduated university and graduate school. This is especially disheartening considering that South Korea is facing a crisis of students being over-educated, with about 70% of all students deciding to enroll in university in 2018 alone****. In consideration of their special circumstances and the natural handicap in education, there are several alternative schools that exclusively educate North Korean defector teenagers.

Ban-seok School, a modest institution with 23 students and 11 instructors, is one of these few alternative schools that cater to North Korean defector teenagers. In an interview with The Yonsei Annals, Ban-seok School explained that they help North Korean defector youth adjust to South Korean society by providing shelter to those without a family and by educating them in preparation of either university or employment. One of the most important responsibilities of Ban-seok School instructors is, undoubtedly, the students’ education. “Due to a long break from education, the students’ basic skills are severely lacking. Of course, there are special cases where students studied hard in school or even enrolled in university back in North Korea. However, even if that is the case, they still do not meet South Korean standards.”

Ban-seok School students span from 20 to 30 years old, although the majority are in their early to mid-twenties. This shows the school’s effort to provide all students, regardless of their age, with an equal opportunity to be educated. However, it is not an easy task. “Their education level differs vastly regardless of how old they are. To provide adequate education, students undergo an assignment test that puts them in one of four classes: elementary school, middle school, high school, and university preparation class. As for English and Math, we provide customized lectures which means that even if a student is in a high school level class, this individual might still have to study basic level English if necessary.” The emphasis on English seems to be related to the students’ struggles with the subject. “It seems that students have the most difficulty in English, because it is usually their weakest subject and because of its importance in South Korean education. Other subjects that students are especially vulnerable in are social studies and history. This is probably because of their lack of basic schooling in the field and the difficult Korean terms that are based on Chinese characters.”

Another mission of Ban-seok School instructors is finding students’ interests, skills, and possible future careers. “Students do not know what they are interested in or what they are good at. Needless to say, they often do not even know what kind of jobs are available to them.” After exploring their individual potential, students are finally able to choose what they want to major in. “Many students aspire to become nurses. A lot of students also enter university as Chinese majors, especially if they had resided in China before moving to South Korea.” While the specialized education programs are a big part of why students enter alternative schools, there is another reason: to help with social adjustment. “There are many instances where North Korean defector teenagers enter a typical South Korean school without proper social adjustment; they are promptly shocked by the disparate youth culture and would then turn to our school for support.” To resolve such an issue, students receive additional classes in civic education, sex education, and debating that help them adapt to the local community.

Even with the support North Korean youths receive from their schools, it is only enough to solve a miniscule part of their problems. “Difficulties in studying, financial burdens, career plans...students wrestle with pretty much everything,” said an official of Ban-seok School. “They are already overwhelmed by the heavy study load, but they also have to work part time jobs due to financial hardships. On top of this, they also have to think about their future.” The situation only gets grimmer when South Korea’s notorious obsession with education is added into the equation. According to the Ministry of Education, 72.8% of all South Korean students have received private education in 2018. When asked whether North Korean students receive private education, the school official explained that it is too much of a luxury. “Students with family members are not given additional financial support from the government. For students who do not have any familial relations, they have to make a living with the 300,000 to 500,000 monthly fiscal support that the government provides.” The devastating truth is that, even if North Korean defector youths have the passion and enthusiasm for education, their financial situation hinders them from dreaming of a better life.

College life of a North Korean defector

Despite the hardships, there are always those that overcome the obstacles in pursuit of their dreams. “I had already finished high school back in North Korea, so when I arrived here and finished my Korea Hana Foundation***** education, I had to plan my own future,” said C, a North Korean defector who requested anonymity before committing to an interview with the Annals. “My decision was to enter university.” C moved from North Korea to South Korea when she was 20 years old and is currently a senior majoring in Korean Language & Korean Literature at the Catholic University. C recalled that she did not even recognize how much peril she was in as she and her family crossed the border and entered China. “It was my first time traveling and leaving my hometown. I was just so thrilled that I did not even realize that we were about to permanently move to South Korea.” C said that she had decided to enroll in university because of her curiosity about college life. “Many of the friends I met at the Hana Foundation decided to get married about a year after arriving in South Korea. However, I wanted to experience college life; it seemed so interesting.”

C also mentioned that the different education system and curriculum in South Korea were certainly big obstacles. “I think that a South Korean high school freshman learns the equivalent of a North Korean university freshman. Also, North Korean students are never required to do any team projects or class presentations, which was why I struggled when I first entered university. I had to start from level zero—finding out what a PowerPoint is and how to make slides.” Another mountain that defector students need to climb over is English class. Most South Korean universities have mandatory English courses that students need to take as part of their graduation requirement. However, the English level of the average South Korean student exceeds that of the average North Korean student, as North Koreans rarely use English after leaving school. Also, since North Korean students learn British English instead of American English, which is more commonly practiced in South Korea, students often find it difficult to follow English lectures in universities. In fact, according to a study conducted by the Korea Hana Foundation, using Korean, studying English, partaking in team projects, and displaying basic background knowledge were key difficulties at university for defector students.

Apart from academic hurdles, C said that she also noticed many students from North Korea suffering psychologically. “Many feel isolated from other South Korean students, mainly because they use a lot of slang and shortened jargon, making it difficult to actively converse with them. The feeling of detachment only gets worse on national holidays like Chu-seok where people gather with their family members and enjoy each other’s comfort; it reminds us of our families back in North Korea.” Many overlook the psychological difficulties of defectors, as economic hardships are more tangible and immediate. However, it is one of the most crucial aspects to consider when helping North Korean refugees adjust to South Korean society. C added that “while being in South Korea gives you a warm bed and a full belly, the loneliness of having left your family, friends, and your hometown lingers with many North Korean defectors.” C said that she too missed the neighborhood where she was born and had lived in for 20 years. “I have heard of cases where defectors return to North Korea because they missed their loved ones and their hometown. I can empathize with their situation.”

C is a member of the University Students’ Association for Unification (USAU), where North and South Korean students gather together to talk about how to unify Korea and discuss the issues related to North Korea via holding conferences. Reunification clubs such as the USAU are a great way for North Korean defector students to create relationships with South Korean students, and bridge networks with other defectors who can empathize with each other and provide mental support. While it is a relief that there are ways students can connect to the community, it begs the questions “What about other defectors that are not in school?” and “How are they supposed to connect with South Korean society?”

As mentioned before, the biggest difficulty that North Korean defectors face is unemployment. “One thing my school can improve on is providing better career advice to students. Right now, the career lectures that the school provides are not very realistic and therefore not very effective. Not all students are aspiring to become CEOs or enter major companies.” C also shared three reasons why employment rates are lower for North Korean defectors than that of South Koreans. “I think discrimination and lack of education are valid reasons. Another factor is ‘high expectations.’ I got the impression that many North Korean defectors expect to get jobs similar to those in TV dramas which are not realistic goals.” Indeed, according to the 2018 Settlement Survey of North Korean Refugees in South Korea, the number one support that North Korean defectors asked of the government was career advice and support for opening new businesses. This research, along with C’s testimony, surmounts to the conclusion that providing specialized consultation for North Korean refugees on how to secure long term economic plans should be a top priority.

* * *

While many are not conscious of it, there are many North Korean defectors living side by side as citizens of the South Korean community. While there are institutions such as the Korea Hana Foundation and Ban-seok school that are working to improve the living standard of defectors, there are still problems: imbalance in education level, economic difficulties, and psychological strain. “My South Korean friends are more like [foreign] friends you meet at exchange school while my friends from North Korea feel more like childhood friends,” C said hesitantly. Indeed, even though North Korean defectors are making every effort to fit into their new lives, the inadequate support they receive from the South Korean society leaves them stranded in a land they should be able to call home.

*Statistics Korea

**OECD

***Chosun.com,Oh My News

****Ministry of Education

*****Korea Hana Foundation: An organization established by the Ministry of Unification in order to educate and support North Korean defectors

Kwon Do-in

amyk990824@yonsei.ac.kr