Anguished families of those abducted and detained in North Korea

YELLOW RIBBONS wave on a pine tree near Imjingak, Paju City. In Florida, the yellow ribbons found on trees were tied by a woman in honor of her husband, who was returning from prison. Those ribbons were meant to represent her forgiveness, but especially her love for him which endured during their long separation. So who tied the 400 ribbons on the tree near Imjingak and what could be their story?

People abducted by North Korea

The yellow ribbons in Imjingak represent the longing of families of the abducted and detained in North Korea. Choi Woo-young, President of FAD (Families of the Abducted and Detained in North Korea), whose father is a fisherman abducted in 1987, is campaigning to tie yellow ribbons, wishing for the abductees' return to South Korea.

During the Korean War, according to a report submitted by the South Korean government to the UN Command over the course of armistice talks, the North Korean cadre abducted more than 82,959 civilians. North Korea needed leaders to build a strong country, so former leader Kim Il-sung created a project to bring intellectuals from South Korea to the North. The abductees were generally from the upper class, but ordinary laborers, farmers and students were taken as well.

The kidnapping continued even after the war. The list includes KAL aircrew, naval forces, but mostly fishermen. Out of the reported 3,765 people, some were luckily able to come back but 487 people are still reported missing.

Psychological and financial damage

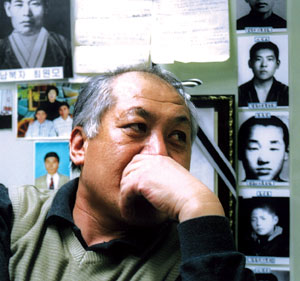

▲ Blinking Back Tears

Choi Sung-yong, president of RAFU tells the story of his family.

(Photographed by Bang Hyun-duk)

The loss of a loved one is a cause of great agony for the families. "I know a mother of an abductee in Incheon who cries out for her son everyday at dawn. Another older woman who lives on Geoje Island always lights a candle in her kitchen waiting for her son to return home. The families still suffer from anguish because of their missing family members and some even suffer from mental illnesses," says Choi Sung-yong, president of RAFU (Representative of the Abductee's Family Union).

Financial problems add to the families' daily lament. Since the abductees are mostly patriarchs of the household, the remaining family members are forced to live in poverty. Mothers, with no special skills, have to be in-charge of the household and take other low-paying jobs. "My mother, who used to be just a housewife, had to work hard in a restaurant. The rest of us had to work as well. We wouldn't have to live like this if our father were with us," says Choi Woo-young.

Innocent but guilty

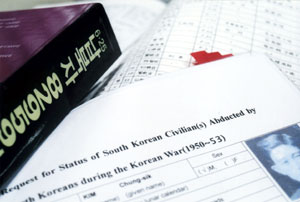

▲ Books and files recording the status of the abductees

Photographed by Bang Hyun-duk)

The government system at the time treated the abductees and their families as suspected criminals. This caused incredible stress for the families even though they had done no wrong. As the government was afraid that abductees would return home as reeducated spies, their families faced constant supervision and interrogation. If they bought a house or their assets grew, they were asked where the money came from, and they couldn't leave their residential district without reporting the move. The government also conducted background checks on the family members, restricting their activities. They couldn't apply for national examinations or enter a military academy, and even had restrictions when getting a job.

The South Korean government even went as far as to torture some of the family members. "Lim Sun-yang, whose brother was kidnapped, moved to an island in order to escape police surveillance. He later died from the after-effects of the 12 days of torture he received at the Gunsan Police Station because he didn't report that he moved,"says Choi Sung-yong.

From 1989, these cruel acts began to gradually cease as a new civilian democratic government was set up, but the families' painful memories cannot be easily erased. A lot of people who were children at that time saw their dreams shattered. Most families still hold grudges and feel uneasy.

Social discrimination has also caused emotional pain. Some would say, "How do we know whether or not the abductees crossed the border of their own will?" These families went through difficult times when anti-communist propaganda was at its harshest and people with a "red complex" avoided them.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights Article 13 Article 16

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each State.

2. Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.

3. The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.

The families' demands and what is left

The families of abductees have been working hard to make their grievance public. Their efforts, including the yellow ribbon movement, hunger strikes, demonstrations and reports to the press have helped them gain recognition. Now more people are aware of them and Congress is trying to make a special law to help them, but the current wave of interest still seems to be too little, too late.

The demands of the families are minimal. They first inquire as to their family member's status, whether dead or alive, and then request the repatriation of the survivors or the ashes of the dead. Other requests include government investigation into the actual conditions of the abductees' families and establishing a special law to provide reparations, not just as a formality, but to help compensate for their pain.

Our attitude toward the families

Students can also make a major contribution. "It doesn't take much. Just show interest, feel sympathy toward the marginalized people of our society and voluntarily try to protect civil rights. Take part in social-outreach activities and help solve society's problems. I hope we can have heart-to-heart communication in an open society of liberal democracy," says Lee Mi-il, president of KWAFU (Korean War Abductees' Family Union). Students should always remember it is their social responsibility to protect human rights and act in ways that benefit society.

How would you feel if one of your family members was kidnapped? Not only that, imagine that you are being tortured and interrogated by the government, and everyone around looks at you with suspicion. It is time to sympathize with the families of abductees, change our distorted prejudices into understanding and do our best to actually help these marginalized people. From now on, when you see a yellow ribbon, you will probably look at it in a different light.

| Q: How were you abducted and what was your life like in North Korea? Q: What about your life in the South, since 2000? | ||||||||||||