- whether to lose or to bring back Korean lost cultural assets

IN THE midst of splendidly flowing garments, which captivated the interested crowd, there still existed sadness gradually increasing inside the people attending Andre Kim’s fashion show. Those were the very prints on the garments, the valuable cultural assets involuntarily taken out yet need to come back, were displayed in front of *Kyungbok-goog* (the Palace of Joseon dynasty) on November 13. “As I realize how important the redemption of our cultural assets from abroad are, I had to hold this fashion show as a Korean,” says Andre Kim. On that day, he also had donated thirty million Won to “74,434”, a MBC program (Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation), for redemption of looted cultural assets held abroad. Led by “74,434,” today, many people start to gain some interest concerning this massive issue.

| ||

Indifferent government

Arising movement in Koreans

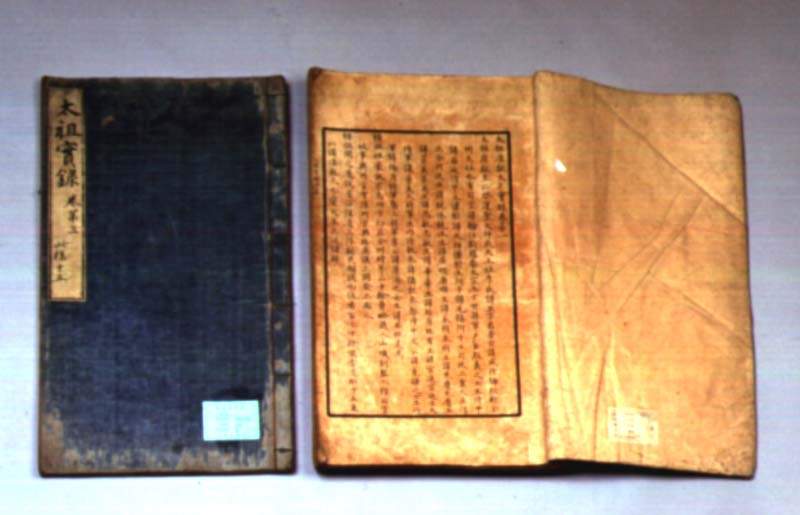

After the redemption of *Bukgwan-daecheopbi*, the individualistic movement gradually transferred into a social movement and gained great attention from the media in 2005. As the Korean government provided its half-hearted effort, some people independently formed movements to obtain our diverse cultural assets. One of these movements is led by *Cultural Action*, a citizens’ organization, with the chairman Hwang Pyung-woo. Joseon Dynasty Chronicles, one of UNESCO’s (The United Nations of Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization) Memory of the World. Hwang, who is associated with MBC, dramatically elevated Koreans’ attention about the importance of the chronicle. Eventually, projects from this citizens’ organization progressed effectively by threatening the Japanese government and ensured that they donated the chronicle back to Korea. Hwang and MBC appraised the case as a huge success, considering that taking back a single heritage from Japan means breaking the “Korea and Japan Agreement” and this can open an opportunity for the next attempt to recover assets from Japan. Hwang proclaims, “We need to take every Korean asset back and it can be meaningful. We should retrieve them by all means including lawsuits, persuasions, donations and auctions.”

The *Jecheon citizens’ organization of cultural assets’ redemption* is a domestic movement that focuses on looted cultural assets. Yoon Sung-jong, a superintendent of this citizen organization, states, “We decided to start this movement in Jecheon considering that there is no national database consisting of the looted cultural assets’ information. Many experts assume that there would be more than one million of them when privately held cultural assets are counted.” This organization tries to take back looted cultural properties using both online and offline methods. Through the Internet, they held cyber-citizens’ campaigns like creating a database of Korean cultural assets on the website. Furthermore, as part of the offline campaigns they held, a signature-seeking campaign and forum to help people understand the importance and the value of the looted cultural properties was also established. Furthermore, they once dispatched a group of people to Japan in order to return *Mongyudoewondoe,* which was painted by famous artist Ahn Kyun during the Joseon Dynasty.

Hye-moon, one of the most active Buddhist priests in this field confessed remorse concerning the manner of redemption and donation, which never seems to be an exemplary method for an inheritance plundeged illegally. Hye-moon insists, “We should attain assets only lost by illegal processes. It’s not significant that we are having a certain inheritance back or not, but it matters if we advance redemption process in a logical way. Constructing an equitable and justifiable system is what we should do first.”

Lastly, some of the companies’ employees also are trying hard to participate in this movement. The employees at Shinhan Bank, for instance, voluntarily donated money and acquired *Cheonsang-yeulcha-boonya-jidoe,* which has value as a national treasure. “We know that returning cultural assets from abroad should be the government’s responsibility. It is, however, not that easy for the government to do, considering the many sensitive conditions. Therefore, what we have discovered was that if someone starts this on a big scale, more employees from different companies will participate with a voluntary donation as well as action,” says Park Il-kyu, a Marketing Manager at Synergy Management Dept. at Shinhan Bank.

The present status and realistic limitations

Prospective solutions

To solve these complicated problems mentioned above, two facts should be constantly restated. Professor of Economics at Yonsei Univ., Cho Ha-hyun advised, “Koreans are the owners of precious assets and have responsibility to hand them down to the next generation.” This mindset, if gathered, should bring about a revolution to create a new redemption policy in Korea.

Moreover, to ensure constant public attention, citizens’ organizations and the government should be well informed concerning the current status of stolen cultural assets. “More forums and dispatches of people to other countries in order to gain and disperse information are needed,” said Yoon. Especially, citizens’ organizations can build an institution that can send university students to museums in foreign countries holding our cultural assets.

Furthermore, special programs necessary for university students to expand the knowledge of assets abroad can be initiated by the Cultural Heritage Administration. Based on the solutions given, we need to adopt a mature and enthusiastic attitude towards recovering cultural assets. “Being fervent in redemption is great, yet rational rather than emotional countermeasures are needed. Korean people sometimes do not react like their like overheated media,” mentioned Park.

However, along with this attitude change, realistic improvement should also be provided. “Better support for the government should be the first priority such as more financial support or consistent care for both cultural assets and its holders. In other words, governmentally organized groups should be established,” says Lee Sang-hoon.

Though the ordinary people’s interest towards the redemption problem has increased in recent years, still the attention from the both the government and the experts is very low. This atmosphere even makes people who are interested in this issue unable to find a proper way to enroll in redemption movement. Only if, those with expertise teach others how to rightfully retrieve stolen assets, then it will not only benefit this rational movement but also encourage world-wide efforts Eventually, small changes originating from “the individual” will bring about innovative redemption traditions which can spread throughout the world.

The movement for redemption has existed for a long time, yet it has been rather individualistic. However, there are some restrictions in these citizens’ organizations’ movements. *Bukgwan-deacheopbi*, for example, is commemorated as a successful paradigm of social liaison. This successful looking case, however, also had gone through some hardships. Hye-moon says that the government mostly comes at the end of the process, when the citizens’ organizations had almost finished the process. He states, “This kind of governmental reaction does not really promote the people’s desire but only depresses it. ‘One man sows and another man reaps’ can be considered as the old saying that fits this problem.”

There are also few more examples regarding cultural assets-redemption that have gone through hardships. For example, the President of Kyungnam Univ., Park Jae-kyu confesses his hardship with media reporting in 1996 because of the Korean people’s harsh feelings regarding this problem. After going through the entire complicating process, he succeeded in achieving agreement in recovering *Derauchi-mungo* (a broad Korean library collection of Derauchi, a former prime minister of Japan)" from Yamaguchi Women's Univ. in Japan. Park informed the Korean media about that redemption, yet the media at once furiously reported the incident to state "redemption of cultural robbery," and Yamaguchi Univ. turned him down. He called for newspapers to rephrase the article by "redemption of outflow-cultural assets" numerous times. Only one paper, however, accepted Park's request and Park finally sent that paper to Yamaguchi Univ. Although at last Pres. Park succeeded in the redemption of *Derauchi-mungo, * and understands the newspaper companies’ attitudes, he questions whether the paper’s reactions were appropriate. “Koreans sometimes become too emotional about this kind of problem, but sometimes it is too harsh and also inflexible to make the situation no better than or sometimes worse than before,” Park insists.

As many people in citizens’ organizations and movements in both in the religious and financial fields, are getting involved in trying to recover cultural assets, it can be said that there is a bright future for this matter. It is, however, still too hard for ordinary people to participate in this movement since there is not much information available. Even the people who are participating in this movement have different concepts toward cultural assets-redemption as well as about whether to bring back illegally transported cultural assets or not. To sum up all the problems, the limited number of people with differing ideas in some restricted areas operating without the government’s help and concern this issue.

However, what about Korean government’s attitude towards the redemption of Korean cultural inheritances? It is shocking to know how the government is seemingly indifferent about retrieving Korean cultural assets from abroad, as well as their only lukewarm support regarding redemption is given for three major reasons. Firstly, the government is especially tepid in obtaining redemption from Japan, the country that possesses the largest number of Korean cultural inheritances. Nevertheless, while regretting the past, official redemption has been historically restricted due to the "Korea and Japan Agreement." The Park Cheong-hee administration and Japanese government mutually consented to an arrangement in 1965. It confines Korea to not attempt any further recovery of Korean assets, which Japan took out during the Japanese imperialism in return for an absurdly small amount of money, four hundred million dollars per year. Even though this agreement was consented to without general Korean citizens’ will at that time, it is the treaty between two nations and so it restricts the Korean government is ability to react towards redemption.

In addition, the Korean government can approach the redemption process only diplomatically. The diplomatic approach, normally done by Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, has an implication of “Would you like to have one-to-one trade with our country?” Though it may sound rational in the beginning, there is no reason for our Korean government to take back assets that had been illegally taken-out by diplomatic means.

Furthermore, disparity in domestic laws regarding cultural assets from nation to nation and even from museums to museums plunges the Korean government into serious difficulties. For instance, the Korean government asked France to give back *woe-kyujanggak* documents, the papers recording Royal history of Joseon Dynasty, in return of importing the TGV, the French high-speed railway system. However, this approach was considered to be a failure, since Korea only received one out of the 63 books, due to complex French laws regulating once imported cultural inheritances from other nations.

Lastly, the Korean government does not invest enough financial support into its subordinate department related to retrieving cultural assets. The government, for example, furnishes only five billion Won to the national museum for purposes of redemption, and it only half that amount for private museums. It is also quite disturbing to know that only one Cultural Heritage Administration person takes care of cultural assets remaining abroad.