Why Korea's Animation Inc. still deserves to be noticed

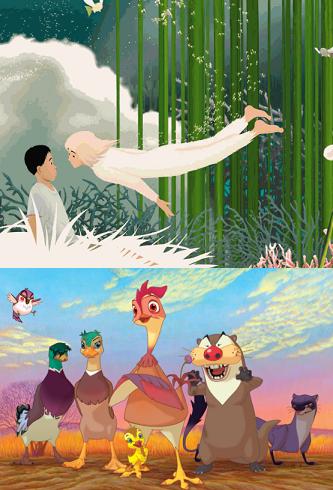

KOREA'S ANIMATION industry seemed so promising back in the early 2000s. The theatrical production My Beautiful Girl, Mari picked up the best animation award at the 2002 Annecy International Film Festival, and Oseam following suit in 2004. The sci-fi film Wonderful Days, a $10 million feat, triggered much anticipation prior to its screening. Korea's animation had undoubtedly reached a turning point.

But that was then. As it turned out, My Beautiful Girl, Mari and Oseam failed to translate critical acclaim into popular appeal. Overridden with clichés and lifeless dialogue, Wonderful Days flopped, and with it floundered the rest of Korea's animation industry. The industry never seemed to fully recover, and many people were left asking the same question: What went wrong?

From reproduction to genuine creation

Well, not much. At least, not from a technical perspective. Korea seemed perfectly poised to shake off its history as a supplier of cheap labor for overseas studios and step up as a nation that could also make its own solid work. More than 30 years of production experience, after all, had transformed Korea into an important animation country. Although Korea's first animations were made into TV commercials as early as 1957, it was in the '70s that the industry boomed. Korea emerged as a sweatshop for overseas animators, with artists painstakingly filled in cels and colored the backgrounds for cartoons like the Simpsons and Rugrats.

But that slowly changed, as Korean animators' expertise in the area started to accumulate. Work hired from overseas was not the only animation being created. Korea began making its own original productions. When theatre features such as Dooly started raking huge profits in the late '90s, the government and various companies jumped into the seemingly lucrative business. "The government started supporting the industry earnestly then, and Korean animations grew a lot because of that," says Kim Young-jae (Prof., Dept. of Digital Culture & Contents, Hanyang Univ.). The names of Korean producers started getting mentioned in international animation festivals. Co-productions sprang up between Korean studios and foreign companies faster than ever before.

Hard times

But what happened afterwards? Interest in the animation industry, however, got snuffed out just as it was beginning to flare. Each attempt at original animated stories fared poorly at the Korean box office each time. After costs of $10 million and seven years of on-and-off production, Wonderful Days barely made $2 million; My Beautiful Girl, Mari and Oseam drew responses that were lukewarm at best.

It is true that a fair amount of riskcomes with producing animation. The painstaking labor that goes into each feature, especially movies - the sketching, copying, delineating, and coloring 20 to 30 frames per second - drives the time and money spent for each production way up. Animators need at least around ₩3 billion to ₩5 billion for a single film. Though that is a negligible amount compared to the ₩100 to ₩120 billion Disney pours into its projects, the succession of mediocre box office results have not helped the industry at all.

It is a vicious circle. Successful works are rare because few works are made in the first place. Flimsy screenplays and marketing - chronic weaknesses - further decrease the probability of good pieces coming out. Finally, flailing productions put investors off from providing the cash that animation directors so desperately need. "There are a lot of animations out there that haven't seen light," says Kim Sae-hoon (Prof., Dept. of Comics & Animation, Sejong Univ.). "My own project got cut off three years ago because the support dried up. It happens all the time in the industry." Audition, a 2009 remake of a popular comic book took nearly ten years for it to screen. Even then, it did not make the mainstream and was shown at a single theatre at the Seoul Animation Center.

The industry's lull, however, is not only experienced by Korea. Japan, homeland to the masters of 2D animation, is finding it difficult to adapt to the increasing amount of 3D animating techniques. There is no doubt: Animation is changing. So is the target audience. Cartoons were traditionally thought of as entertainment for children only. But companies like Disney have slowly realized an awful truth: The animation market is shrinking. "Besides the plummeting birth rate, kids nowadays have so many other distractions," says Kim. "There's school, afterschool activities, cable TV, computer games, the internet - kids just have less time to watch animation." No wonder Hollywood has expanded its target audience from just kids to the entire family. "Korea doesn't really realize that need yet," says Han Chang-wan (Prof., Dept. of Comics & Animation, Sejong Univ.). "Most of the animations that are being made - especially TV series - are targeted at young children. There isn't much variety out there."

Necessary renaissance

It is easy to wonder why domestic animation needs to be revived at all, if it is beleaguered with so many problems. But animation has the advantage over other public entertainment such as movies or musicals of being very transnational. Once properly dubbed the same animated story can be enjoyed by a Russian, a Brazilian, or a Korean quite comfortably. European and American children rage over Pokemon just as eagerly as any Japanese child; Korea's TV show Pororo has gained popularity both at home and abroad. Dubbed versions of numerous Japanese animations slipped into Korea in the '70s, making the children believe that the cartoons they watched were Korean.

But most important of all, "nations pay great attention to preserving domestic animation because it affects young children so much," says Han. "Animations are one of the first forms of entertainment that the kids come in touch with, and no one can ignore the cultural effect the cartoons can wield." France started its own animation protection law after Japanese animation dominated the nation's TV cartoon channels in the 1990s. Not only did the sales of Japanese cartoon character products increase, but the government became alarmed by how many French teenagers started showing signs of imitating, sometimes even worshipping, Japanese culture.

Breaking the vicious circle

Then what must be done to Korean animations to fix its problems? The government already provides several support projects for the industry, but that is not enough. Critics pinpoint various necessities, including the need to nurture creative animators, to expand the number of co-productions, and to produce tighter, better-developed screenplays.

Among the improvements needed to be made, Kim Sae-hoon emphasizes the necessity of a paradigm shift. "The definition of animation is so ambiguous now," he says. "People only regard the traditional 2D- or 3D- TV series or theatrical productions as animation. But animation is applied in so many other areas, such as in the special effects rendered in films. Just look at The Lord of the Rings and The Matrix, where practically half the movies consists of computer graphics. That is all work done by animators. How do you distinguish animation from movies in cases such as these? The animation industry is changing - what the industry must do is adapt to the changes and upgrade itself to respond to the new needs of the public. Compared to the past, the appeal of traditional animated movies has begun to falter. It's necessary, therefore, not only to focus our energies into fostering the traditional forms of animation, but to the animation integrated into ordinary film as well."

Most importantly, critics agree that animators should constantly try to create new works. From that pool of productions pieces should then appear that demand media and public attention. "Hotly debated animations need to come out continuously," says Kim.

That is what Oh Sung-yun (Animation director, Odotogi) is hoping to do with his current project. He has been preparing, for the last five years, a theatrical production remade from a popular children's storybook. "I'm hoping that the film turns out to be successful - if it does, it'll also help enliven the animation industry," he says. Having worked with Korean animation for the last two decades, he understands how difficult animators are currently finding the situation. Oh is still hopeful despite the odds. "I believe in the potential of Korean animation," he says. Very well. Now it is the public's turn to believe it - or at the very least, to take some interest into Korean animation. After all, public indifference is a scary thing.