Documentaries: The Tightrope-Walk Between Fact and Fiction

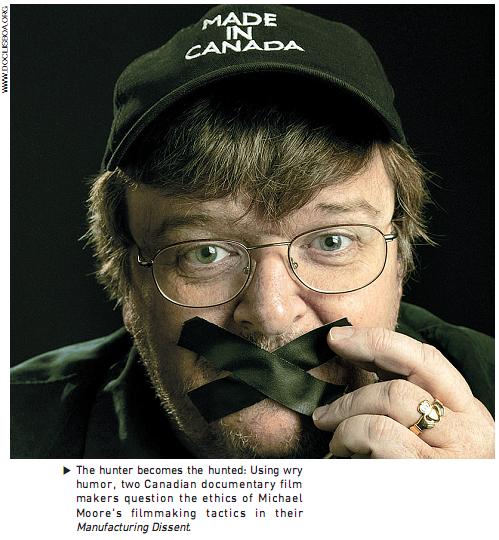

MANIPULATING THE truth is easier than you might expect. Consider Manufacturing Dissent, a Canadian documentary that questions Michael Moore's dubious filmmaking tactics. Its two directors thumb their noses at the creator of Roger & Me, Fahrenheit 9/11, and Sicko by doing exactly what they accuse Moore of: wrenching facts out of context. Letting audiences know an interview has been distorted is part of the fun. In one scene, a man appears to be a hardcore Michael Moore fan -- "His films are so great!" he exclaims. The man is cut off right there. But the rest of the footage, revealed only at the end of the documentary, exposes him as an attention-seeker who jokes about how he gets James Bond mixed up with Michael Moore. Same subject, same footage, and such different results. It makes the audience wonder: How about other films? Can we believe what documentaries show us?

The making of manipulation

We take it for granted that documentaries tell the truth. After all, the very word documentary, stemmed from "to document", means to verify, to record, and to authenticate what is real. Ironically, no other film genre has been so questioned over its veracity and legitimacy as the documentary.

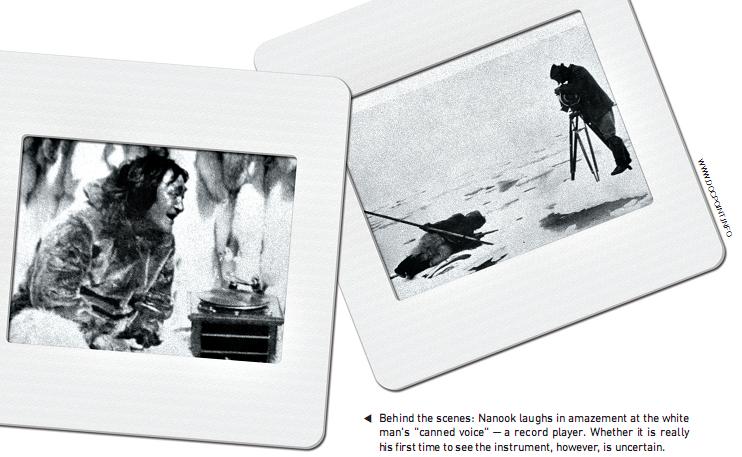

Accusations of fakery have plagued many such films. In 1922, Robert Flaherty captured Inuits gawking at record players and harpooning seals in Nanook of the North, though in real life they listened to the radio and shot guns. Then, in 1958, Disney filmmakers pushed lemmings off a cliff for White Wilderness, making it seem like the animals had voluntarily flung themselves over the edge. (Hence began the public myth that lemmings commit mass suicide). One of the biggest scandals, however, came with The Connection, an hour-long British documentary that claimed to expose a new drug route for smuggling cocaine from Columbia to Britain. As observed by The Daily Mail, "large parts of it were complete fabrication."

Public broadcasting systems have not been an exception. In Korea, critics blasted KBS for passing trained otters off as wild ones in its 1992 nature documentary. A year later, Japan's NHK aired an apology for faking the near-death experience of a crew member in its documentary on the Himalayas. Then critics attacked KBS for another deception in its 2009 documentary on owls... the list goes on.

The documentary paradox

Films like White Wilderness or The Connection are damning examples of deliberate fabrication. Not all documentaries, however, can be judged so easily. For one thing, a documentary filmmaker could decide to sacrifice a certain truth for artistic values. Or he could also "dramatize or stage a certain event to make the truth easier to understand," says Shin Un-hoon (Producer, TV Programs Headquarters, SBS).

Take Nanook of the North. Yes, the film was rampant with anachronisms. And yes, Nanook's family members were not real, but picked to fit Flaherty's romantic ideal of what an Inuit family should look like. But considering it was 1922, "Flaherty did a pretty good job at repainting a realistic portrait of what he believed was the true spirit of the arctic life led by the Inuits," says Hong Soon-chyul (Prof., Dept. of TV Broadcasting, Korean National Univ. of Arts). If Flaherty encouraged Nanook to hunt like his ancestors, it was because he wanted to celebrate the Inuit life in its virgin form, before it came in contact with the Europeans. He lived there for two years as he shot the film, explaining to his hosts in detail why he was there, what he wanted, and sharing with them the results of his footage. It is true that failing to inform audiences what was staged and what was not isproblematic. But the staging itself? That can be condoned according to the particular situation.

Ultimately, the truth is this: documentaries are, by definition, a paradox. They commit themselves to show a subject just as it is, raw and unmediated. But the very act of threading disconnected material together into a coherent story already perverts the truth."I can choose to film an object from above, or obliquely, or from the bottom," says Choi Jin-sung (Film director). "And that same object will look different each time." A film can never be completely objective. Every single decision that a director makes n choosing whom to interview and what to shoot, inserting sound effects, and editing n echoes what the director feels about his subject.

Even if the director were somehow able to eliminate his voice from his own film, the camera becomes another variable. The very act of shoving a camera into a person's life or a natural environment is bound to affect it. Calvin Pryluck makes this very clear in his essay on why filmmakers are ultimately "outsiders" when recording the lives of others. He writes of On the Pole, a documentary on Eddie Sachs, who was one of the most popular and greatest auto drivers of all time. After Sachs loses a speed car race, he "shows himself being afraid to show disappointment, trying to act 'natural,' but not being sure what natural means in terms of the image he wants to present of himself." What is the "truth" here? The fact that Eddie Sachs would candidly show disappointment if he were not in front of a camera, or the fact that he is conscious of the camera lens right now? What the camera captures may not always be accurate n Daddy's Girl, for example, shocked the public when it was exposed that its filmmakers had been duped by a pair of lovers who posed as daughter and father.

The ever-fading boundary between fact and fiction

Of course, efforts to film things just the way they are have always been made. Fly-on-the-wall documentaries (films that candidly observe the situation as a fly on a wall would) became possible only with the introduction of light, handheld cameras. In the '50s and '60s, a young generation of American and European filmmakers pioneered Direct Cinema, or Cinéma Vérité -- a rigorous form of documentary that filmed real people without any scripts, which did not use voice-over narration and avoided the producer's intervention as much as possible. Filmmaker Frederick Weisman, one of the most prominent American documentary filmmakers of all time, strove for authenticity to such a point that "he hated editing his clips," says Kim Dong-won (Prof., Dept. of Visual Broadcasting, Korean National Univ. of Arts). "He'd leave chunks of interviews barely touched, and at times, let them run for as long as ten minutes." But even Weisman said that although his films may have been based on "un-staged, un-manipulated" events, the editing and shooting would be "highly manipulative […] What you choose to shoot, the way you shoot it, the way you edit it and the way you structure it […] represent subjective choices you have to make."

The increasingly blurry distinctions of the documentary add another dimension to the documentary's quandary of representing the truth. "The documentary is a slippery genre to define," wrote documentary critic John Ellis. There are, of course, the more traditional documentaries n direct cinema, TV documentaries, nature documentaries, historical documentaries, and so on. At the same time, though, a surprising amount of new documentaries have fast eroded the distinction between fiction and reality. Several documentary films delve into the director's own personal life and thoughts. Others tackle social issuesby putting the director in front of the camera, as does Michael Moore. In the documentary film The Yes Men Fix the World, political activists pose as top executives and say "yes" to all the moral decisions that the corporations refuse to do, such as finally cleaning up the site of industrial accidents. Their pranks expose the biggest and worst of the world's greediest companies. The wildest cocktail of fact and fantasy, however, is made within a new type of film called mocumentaries, or fake documentaries. These films mimic the documentary method of unraveling events, and usually comment on current events through satire.

Scenes made with a conscience

Naturally, it becomes impossible to define exactly what is acceptable and what is not in documentaries. "There are so many ways to recreate reality through the screen," says Hong. Sometimes having a director act like a showman in his own film can be less subjective than having a third-person narration. "I chose to narrate my documentaries in the first person because it lets people know that the films reflect my subjective thoughts," says Choi. "You refer to the third-person narrative as 'The Voice of God'. That anonymous and omniscient voice may seem extremely objective, but that isn't necessarily true."

Consequently, conscience becomes the only way to distinguish an ethically-made documentary from its opposite. "It becomes dangerous once you start lying," says Kim. "Because lying is so easy. And most audiences are ready to believe those lies just because the film is called a documentary."

For the public, on the other hand, it is easy to think that documentaries should be always strictly objective. Though facts should not be abused as a rule, at times, harmless distortions can sometimes offer an alternate, more effective way of conveying the truth.

Nice work on your article very true for truths sake.